History Department Acknowledgement of the Tongva and Greater Indigenous Lands occupied by the University of Southern California

The Van Hunnick History Department of USC acknowledges our presence on the ancestral and unceded territory of the Tongva people and their neighbors: (from North to South) the Chumash, Tataviam, Kitanemuk, Serrano, Cahuilla, Payomkawichum, Acjachemen, Ipai-Tipai, Kumeyaay, and Quechan peoples, whose ancestors ruled the region we now call Southern California for at least 9,000 years. Indigenous stewardship and rightful claims to these lands have never been voluntarily relinquished nor legally extinguished. We pay respects to the members and elders of these communities, past and present, who remain stewards, caretakers, and advocates of these lands, river systems, and the waters and islands of the Santa Barbara Channel. As a department of professional historians, we undertake an obligation to present truthful facts about USC’s specific occupation of Tongva lands. (We hope that other units of this university will also make an acknowledgement such as this, but we do not presume to speak for more than our own department in this document).

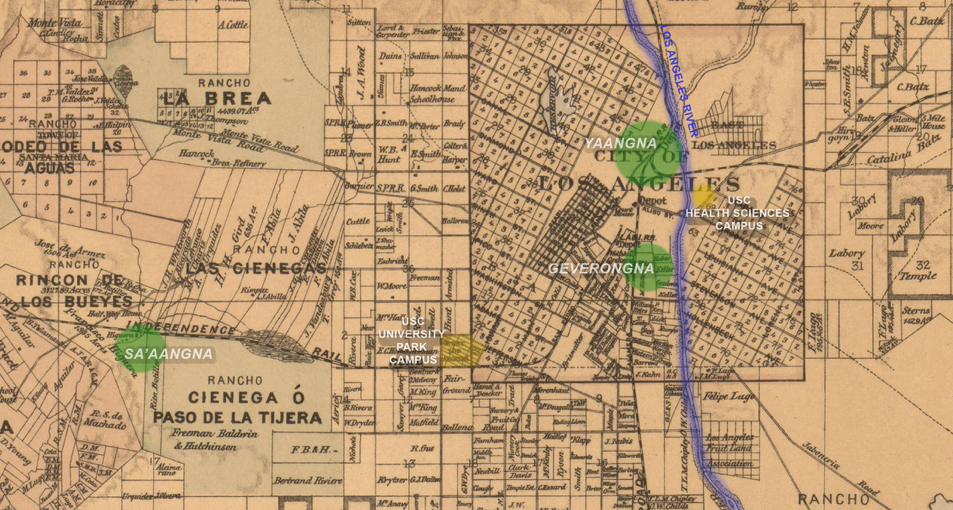

Tongva lands and islands were traditionally ruled by autonomous village-states, knitted together by kinship, language, culture, and institutions. The University Park Campus and the Health Sciences Campuses of USC occupy unceded territory belonging to the villages of Yaangna (Downtown Los Angeles and East LA); Geveronga (Pico-Union); Sa’aangna (Baldwin Hills); Huutnga (Compton); and Ochuungna (South Pasadena). People of these village-states were deeply interconnected by kinship ties and trading relations. They spoke the same language and maintained a regional community that stretched from the San Gabriel Valley to the Southern Channel Islands, and from the Hollywood Hills to the San Pedro Bight (the LA Harbor). Prior to the Spanish conquest that began in 1769, the people of these villages intensively managed their lands, by cultivating, pruning, seeding, and above all, by seasonal burning. The areas surrounding USC’s two main campuses were, until about 1800, principally oak and riparian woodlands, oak savannas, and prairie flowerfields. Intensive landscape management by the Tongva villages yielded an abundance of acorns (their principal staple), and the seeds of annual herbs, such as chia, and the birds, animals and fish, whose numbers were also magnified by the sustainable landscape management of the Tongva and their neighbors. Catastrophic disruption of this ancient political economy by the invading Spanish Empire, plus mass violence, forced confinement and forced labor under occupying Spanish, Mexican, and U.S. regimes diminished the Indigenous populations in appalling numbers. But the Indigenous peoples of Southern California survived through three conquering regimes and still thrive today in an unbroken chain linking past to present. The following paragraphs provide context and details of this history for just one place–the University Park Campus of the University of Southern California–so that recognition of Indigenous rights to the land, sky, and waters of this region shall have a factual basis worthy of an institution dedicated to truth, knowledge, and the pursuit of human rights. The University Park Campus of the University of Southern California sits closest to the former villages of Yaangna, Geveronga, Sa’aangna, and was most probably controlled by them for thousands of years. In traditional Tongva societies, all consumable resources–every oak tree, every patch of flowerfield, every wetland and firewood gathering area–was either the collective property of the village as a whole, or the hereditary property of a particular family. The University Park Campus was for countless generations, a treeless flowerfield burned and harvested by either the Yaangvit (People of Yaangna), the Geverovit (People of Geveronga), or the Sa’aavit (People of Sa’aangna), or all three.

Yaangna was a primary, or “capital” village among the Tongva, one of the most important central places of the entire region (which is why the Spanish chose it for the site of Los Angeles). Yaangna controlled access to, and the crossing of the LA River at its only year-round flowing segment. Geveronga was a secondary (smaller, less powerful) village, lying just to its south-west, as was Sa’aangna, nestled against the Baldwin Hills to the west. The precise boundaries between the gathering areas of these three village-states are lost to us now, and it is possible that these and other villages shared overlapping gathering rights to the future University Park Campus area. Traditional, pre-European geographies were highly complex: commonly segmented, non-contiguous, and overlapping, depending on the context (resources, jurisdictions, kinship alliances, enmities, religious societies, guilds, trading relationships etc.). Tongva villages specialized in different commodities, depending upon their location. The Tongva villages closest to the site of the USC University Campus area focused on terrestrial resources, while those along the Pacific Coast and the southern Channel Islands specialized in marine resources. They all traded with one another, and with the Chumash, Tataviam, and many other neighbors, in a vast and complex regional civilization, tied together by ocean-going vessels called Ti’atby the Tongva and Tomolby the Chumash (see “Rethinking the Coast with the Ti’at society”).

The Los Angeles River, known to the Tongva as ”Paayme Paxaayt” (West River), and to the Spanish as “Rio Porciúncula” drains a vast watershed that encompasses the entire San Fernando Valley and much of the San Gabriel Mountains. On the floors of the San Fernando Valley and the South Los Angeles flood plain, the river sinks into the deep alluvial gravels during the summer. The Tongva villages of Yaangna and Geveronga sat advantageously near the only place where the LA River flows above ground throughout the entire year, forced upward by bedrock through the gap between the Hollywood Hills and the San Gabriel Foothills called the “Glendale Narrows.” In this region’s climate, of cool wet winters and hot dry summers, the Los Angeles River often floods violently as it exits the Glendale Narrows, and has shifted its course–both above and below the Glendale Narrows, countless times. As recently as the years 1815-1825, it shifted suddenly westward, directly across the future USC/UPC campus site. Indigenous peoples of the Los Angeles Basin depended upon the waters of the Los Angeles and San Gabriel River watersheds, but they knew, from thousands of years of experience, never to build on such a site. Instead, when it was not under the course of Paayme Paxaayt (the LA River), they would have burned the open land seasonally to maximize the yield of flowering annuals, driving rabbits into traps as they did so.

The Yaavit, Geverovit, and Sa’aavit lost control of this seasonal flowerfield where the University Park Campus sits today, during the period of conquest and colonization by the Spanish, Mexican, and U.S. regimes (1769-present). The Spanish established a colonial military, religious, and economic base at Misíon San Gabriel Arcángel in the 1770s, relocating thousands of Tongva and their neighbors from scores of surrounding village-states. The two principal Spanish Missions in the Los Angeles Basin, Misión San Gabriel Arcángel (founded 1771) and San Fernando Rey de España (founded 1787), were colonial haciendas, supplying the economic backbone of the entire Spanish occupation of the province they called “Alta California.” Their gigantic herds of cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs (numbering in the tens of thousands), many acres of grape vines and fruit trees, along with craft workshops, all depended on the forced labor of the oppressed Tongva and their neighbors. The Spanish eradicated the Indigenous economic base by displacing the flowerfields with European grazing grasses and cutting the ancient acorn-bearing oaks (typically 300-500 years old) for lumber. People of the many Tongva villages were forced into the deadly missions at different rates, with many peripheral villages remaining independent and supplying refuge to the Indigenous who escaped the missions.

The Indigenous peoples of Southern California contested and resisted the conquering regimes from the very outset. Kumeyaay, Ipai-Tipai, and Quechan peoples rose against Misíon San Diego in 1775, and a major uprising in 1785 against Misíon San Gabriel, led by the Tongva rebel Toypurina, was only barely suppressed. The Quechan closed the Colorado River crossing to Europeans for 50 years beginning in 1781, forcing the Spanish and Mexicans to enter Southern California either by sea or via the Santa Fe Trail at Cajon Pass (near present-day San Bernardino), far to the north and across the Mojave desert. Large confederations of Chumash and their Yokut and Tataviam neighbors rebelled against Misíon Santa Inés, Misíon Santa Barbara, and Misíon La Purisima, in 1824. Between these dates thousands of people committed everyday acts of resistance and escaped, or attempted escape, from the deadly forced-labor missions to free villages in the surrounding mountains (Yokut and Serrano) and deserts (Cahuilla, Mojave, Apache, Quechan). Ongoing efforts to obtain federal tribal recognition, to re-acquire property rights to lands, to re-assert traditional Indigenous knowledge about the ecological management of the Los Angeles Basin, and to be included in the governance of the region are today’s manifestations of the resistance to conquest.

The genocidal process that depopulated the Tongva villages and destroyed their economies is visualized in this animated map by scholars working with the mission baptismal and death records (Hackel, et al 2014). The Spanish military confined people from all over the San Gabriel Valley region, including not only Tongva, but also Cahuilla, Serrano, and Yuman people from the south, to Misíon San Gabriel. Baptised to Christianity there, and held in an unfree status as “neophytes” (children) under the spiritual guidance and legal authority of the Franciscan “padres” (fathers), these captive people were subsequently called by the Spanish “Gabrieleños,” later anglicized under the U.S. regimes to “Gabrielinos.” Because the majority (but by no means all) of those held at Misíon San Gabriel were from Tongva villages, the group name “Gabrielinos” came to be equated with the Tongva people as a whole. Likewise, the many ethnic groups confined to Misíon San Fernando Rey de España, came to be called “Fernandeños,” even though the majority were Tataviam.

Deppe’s painting depicts the landscape in the aftermath of the Spanish conquest of the Tongva and neighboring Indigenous. In the foreground is an independent, “gentile” or un-baptized and therefore still free, Tongva village (possibly Shevaangna, at Whittier Narrows on the San Gabriel River and the Rio Hondo). On the left are the large barracks in which more than 1,000 Indigenous–largely Tongva–were required to live. The largest building in the center are the many workshops in which Tongva and other Indigenous peoples manufactured all of the necessaries for the Spanish rulers. To the right is the Mission chapel itself, which like every other building in the complex was the work of Tongva artisans.

The autonomy of Yaangna and Geveronga ended in 1781, when settlers in the Anza Expedition of that year dismantled the two villages and inscribed an imperial land grant of four square Castilian leagues. The Spanish title to this land was imposed under authority of King Carlos III of Spain (reigned 1759-1788), to the “Pueblo de Nuestra Señora, Reina de Los Ángeles del Río Porciúncula.” That grant included a monopoly on the water rights to the entire course and watershed of the Los Angeles River. That imperial grant, centered on what is today La Placita, popularly known as “ La Plaza Olvera,” along with its water monopoly, still forms the legal basis for ownership and control by the City of Los Angeles. The University Park Campus of USC sits adjacent to, and just on the south-western edge of that grant’s territorial boundaries (today’s Jefferson Blvd between Figueroa and Vermont). While most of the region outside of these pueblo (town) lands, was eventually carved-up into large privately-held pastoral estates called “ranchos” by the Spanish and Mexican governments, the place now called the University Park Campus was never so granted, and remained an open, public grazing land (when it was not submerged under the course of the Los Angeles River, as in the 1820s). Titles to these lands were obtained in public land sales by U.S. citizens after the U.S. conquest of 1848-50, and became the property of Isaias W. Hellman, Ozro W. Childs, and John G. Downey, who assembled a tract called “West Los Angeles” in 1876, and donated these lands to the Board of Trustees of the University of Southern California in 1879.

This cadastral map from 1877 shows the newly-assembled parcels donated by Ozro W. Childs, Iasias W. Hellman, and John G. Downey, and donated by them to the Trustees of the University of Southern California in 1879. Their donation, a tract called “West Los Angeles,” lay at the south-west corner of the original four square league Spanish pueblo boundary. That grant, two leagues on each side, is inscribed as a distinctive street grid oriented north-west to south-east within the U.S.-period grid, which is oriented on the cardinal N, S, E,W axes. Overlaid in green are the approximate locations of three autonomous Tongva village-states: The capital village of Yaangna, at the center of present-day Downtown Los Angeles; Geveronga, downstream from Yaangna, on the LA River’s west bank. Sa’aanga sat at the eastern foot of Baldwin Hills.

Most of the Tongva who had been Yaavit, Geverovit, and Sa’aavit suffered a common fate with those from other villages. Unlike so many other Indigenous people across North America, the Tongva were never removed to so-called “reservations.” Instead, after the collapse of the Spanish missions, accelerated by their disbandment or “secularization” in the 1830s during the Mexican regime, Tongva and their neighbors were compelled to work as ranch hands, water carriers, and servants for Mexican and U.S. citizens.

Those who survived into the period of United States rule after 1848 were unprotected by U.S. law. California law from the 16 April 1850 Act Concerning Criminal Proceedings, prohibited “Indians” from testifying against “Whites.” All California Indigenous were also subject to bound labor law enacted by the first California State Legislature (Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, Chapter 133, Cal. Stats., April 22, 1850),which allowed any US citizen to force Indigenous people to labor without wages by paying a fine or bidding for control of children and adults in open auctions. The depredations by the United States against the Tongva took place in a context of mass killings of Indigenous throughout the State of California, sanctioned and funded by the California state government, in violent campaigns to end Indigenous autonomy in the Great Central Valley, gold regions, and the Mt. Lassen area. While scholars, Indigenous and others, have described these massive violations of human rights, some calling it an American genocide, much remains to be told, and legal restitution has never been achieved. The Tongva today do not enjoy even the limited rights and privileges accorded by federal tribal status, as they remain unrecognized by the U.S. government.

The founders of USC created the university in 1880, 99 years after the destruction of Yaangna, Geveronga, and Sa’aangna and the dispersal of the Yaavit, the Geverovit, and the Sa’aavit. But the descendants of those and the many surrounding Tongva village-states live on today, some of whom have become elders and tribal officials who continue to care for Tongva lands and waters, and carry on the leadership of this region’s ancient civilization. They remain stewards, caretakers, and advocates of these lands and its many resources. The Indigenous of the Los Angeles Basin tell their own stories in many different ways, and we encourage readers to visit the websites of the Tongva and their neighbors, in the selected links below. Several academic departments at USC offer instruction and research programs in Indigenous studies, which we also encourage readers to explore.

- “Perspectives on A Selection of Gabrieleño/Tongva Places”, by Craig Torres, Cindi Alvitri, Allison Fischer-Olson, Mishuana Goeman, and Wendy Teeter.

Selected Bibliography

This brief history is based on many sources. The following are larger synthetic works, based on many sources cited therein:

- M. Kat Anderson, Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.)

- Deverell, William, “Remembering a River,” in: idem, Whitewashed Adobe: The Rise of Los Angeles and the Remaking of its Mexican Past(Berkely, 2006): pp. 91-128.

- Ethington, Philip J., Beau MacDonald, Gary Stein, William Deverell, Travis Longcore, “Historical Ecology of the Los Angeles River and Watershed: Infrastructure for a Comprehensive Analysis,” Study funded by the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation. Published online March 2020: https://lalandscapehistory.org/

- Ethington, Philip J. “Ab urbe condita: The Regional Regimes of Los Angeles since 13,000 Before Present,” in William Deverell and Greg Hise, eds, A Companion to Los Angeles(Blackwell Companions to American History) (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 2010): 177-215.

- Haas, Lisbeth. Saints and Citizens: Indigenous Histories of Colonial Missions and Mexican California. Berkeley: UC Press, 2014).

- Hackel, Steven W. Children of Coyote, Missionaries of Saint Francis: Indian-Spanish Relations in Colonial California 1769-1850. (University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

- Hackel, Steven W. “Sources of Rebellion: Indian Testimony and the Mission San Gabriel Uprising of 1785,” Ethnohistory, Volume 50, Number 4, Fall 2003, pp. 643-669.

- Jurmain, Claudia, and William McCawley, O, My Ancestor: Recognition and Renewal for the Gabrieliono Tongva People of the Los Angeles Area(Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2009.

- Lightfoot, Kent G., and Otis Parrish, California Indians and their Environment: An Introduction. (UC Press 2009).

- Madley, Benjamin. An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873(Yale UP 2017).

- McCawley, William, The First Angelinos: The Gabrielino Indians of Los Angeles. (Morongo, California: The Maliki Museum Press, 1996).

- Monroy, Douglas. Thrown Among Strangers: The Making of Mexican Culture in Frontier California. (Berkeley: U.C. Press, 1990).

- Timbrook, Jan. Chumash Ethnobotany: Plant Knowledge Among the Chumash People of Southern California. (Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History 2007).

- Welch, Rosanne, “A Brief History of the Tongva Tribe: The Native Inhabitants of the Puente Hills Reserve.” (Department of History, Claremont Graduate University Claremont, California). Can be found at this link.

- Zappia, Natale. Traders and Raiders: The Indigenous World of the Colorado Basin, 1540-1859. (University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

Note on Authorship:

This acknowledgement was co-authored for the USC Van Hunnick History Department by Philip Ethington and Wolf Gruner, with contributions by Alice Baumgartner, Willie Cowan, Peter Mancall, and Julia Lewandoski.