Port of Los Angeles, one of the United States’ premier gateways for international trade and commerce.

Source: Green Fire Productions via license CC BY-ND 2.0.

20. Port and Cargo Safety

Author: Dr. James A. Fawcett, USC Sea Grant Maritime Policy Specialist/Extension Director (retired)

Media Contact: Leah Shore / lshore@usc.edu / (213)-740-1960

Throughout the world, seaports are a nation’s front door to its trading neighbors. And in a world where products are widely traded between nations, our ports have relied upon policies that behave like screen doors, open to breezes while keeping out only the peskiest of pests. All of that changed after 9/11.

The September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center was, and remains, a challenge not only to the U.S. but also to the world. How can we be vigilant about our transportation system and yet simultaneously facilitate the movement of goods—and people—around the world? Since terrorists could utilize publicly accessible airliners as weapons, elected officials also questioned the security of the maritime goods movement system, in which goods are commonly transported worldwide in virtually identical and anonymous standard intermodal cargo containers. Could a cargo container be weaponized, they questioned, when the marine transportation supply chain moves over 90% of cargo traded between nations?

Inspired by these concerns, the U.S. Congress took action to augment the existing national maritime security system[1] by implementing an additional layered cargo security system through three important aspects which are worthy of our attention: 1) the umbrella provisions of U.S. law that provide standards for port security including implementation of the International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS), regulations imposed by the International Maritime Organization that affect worldwide shipping; 2) the Container Security Initiative that guards cargo entering the U.S. from 58 foreign seaports and; 3) the Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism, a voluntary pact establishing security protocols between shippers and U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Source: U.S. Department of Homeland Security

1. Marine Transportation Security Act of 2002 (MTSA)

Legislated by the U.S. Congress soon after the attack, the MTSA provides a wide array of tools for the maritime cargo industry. These tools include personnel security, facility provisions, and design guidelines that ensure that cargo both on ships and on the docks is protected. The MSTA also ensures that the public is protected from risks that the cargo itself may present. Among the more prominent provisions are the following:

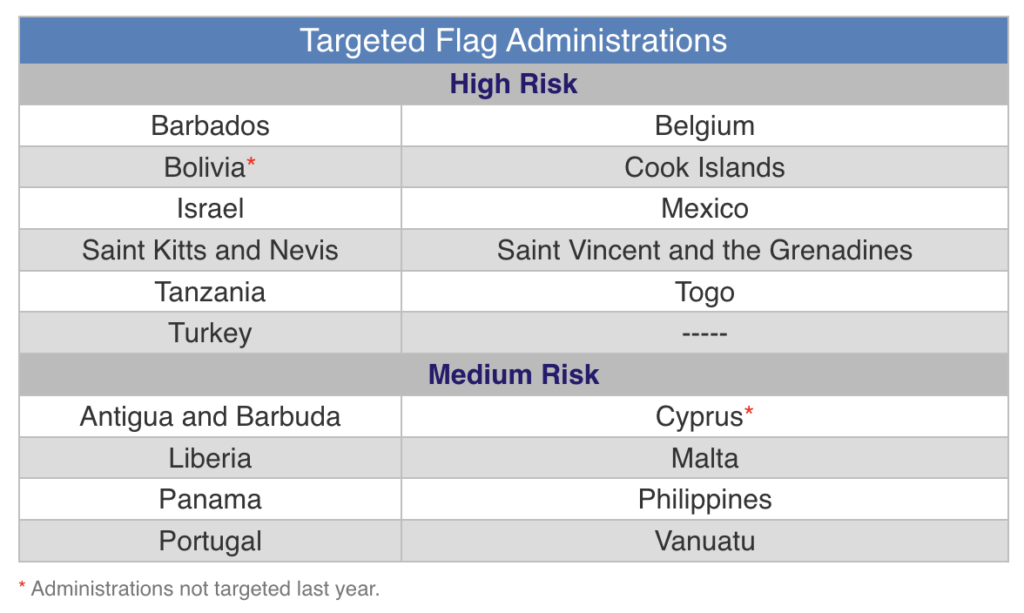

Foreign Flag “Watch List”: The U.S. Coast Guard has developed a list of foreign-flag carriers whose past performance makes them poor security risks, and this “watch list” is distributed to U.S. Coast Guard, Customs and Border Protection, and other federal agencies with cognizance over vessel and goods movements in U.S. seaports.

Maritime Transportation Security Plans: Vessel operators and owners are now responsible for preparing and maintaining updated vessel security plans. The MTSA applies only to U.S. flagged vessels, but it is also harmonized with the International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS) applying to vessels of all nations. This ensures that similar provisions apply to vessels flagged (registered) both in the U.S. and internationally.

Foreign port assessments: The U.S. Coast Guard also is required to assess port security at foreign ports and to note deficiencies. If the foreign ports pose an immediate threat to the U.S., they are notified to correct security deficiencies. If they do not comply satisfactorily, cargo from these ports may not be permitted entry into the U.S. Again, this is the U.S. emphasizing that the provisions of the ISPS Code affect the movement of goods bound for U.S. seaports.

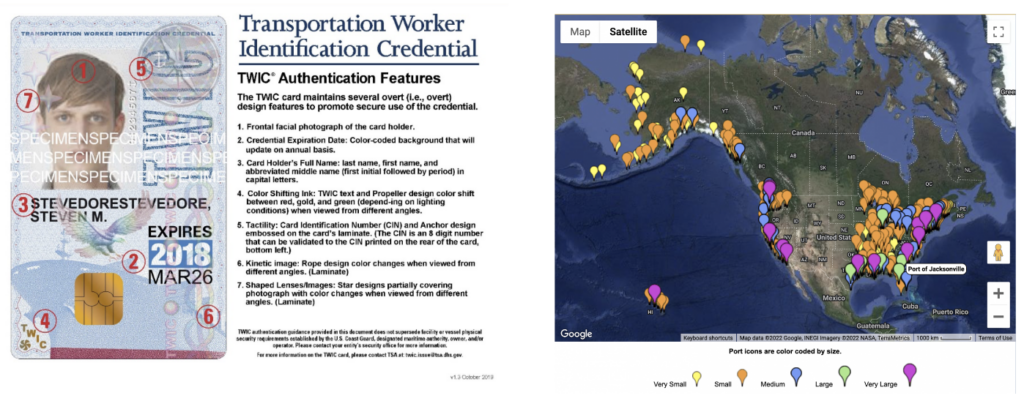

Transportation security identification: The identity of vessels headed to the U.S. at foreign export ports is vitally important, but thorough security also requires that the identity of dockworkers within the U.S. be obtained, verified, and recorded for any person to gain unsupervised entry to secure port facilities. This has been implemented by the so-called TWIC (Transportation Worker Identification Credential) system, in which dockworkers’ identity is verified and entered into a searchable security database and each must carry an ID badge similar to those worn by employees at U.S. airports.

Automated Identification System for Vessels: Regulations adopted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in 2000 require that each vessel of 300 gross tons or greater engaged in international trade, all vessels greater than 500 tons not engaged in international trade, and all passenger vessels irrespective of size transmit via Very High Frequency (VHF) marine radio and often by satellite: its identity, course, heading, speed, location, and other pertinent information.[3] The system has been required for all vessels entering the U.S. since 2004 and applies worldwide under regulations of the IMO.[4]

International Seafarer Identification: Since 1958, the International Seafarers Document Convention of 1958 (No. 108) has required all seafarers, both officers, and non-rated workers, to carry a standard form of ID, the Seafarer’s Identification Document (SID).[5] Post-9/11 with the implementation of increased concern for the identity of seafarers, the convention was amended into the Seafarer’s Identity Documents Convention (Revised) of 2003 (No. 185), requiring enhanced verification of the identity of seafarers when they go ashore on shore leave (without visas) while in a foreign country. Working with the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the standards and form of the SID have been enhanced into its current form, another means of implementing dock security worldwide and implemented in the U.S. through the MTSA.

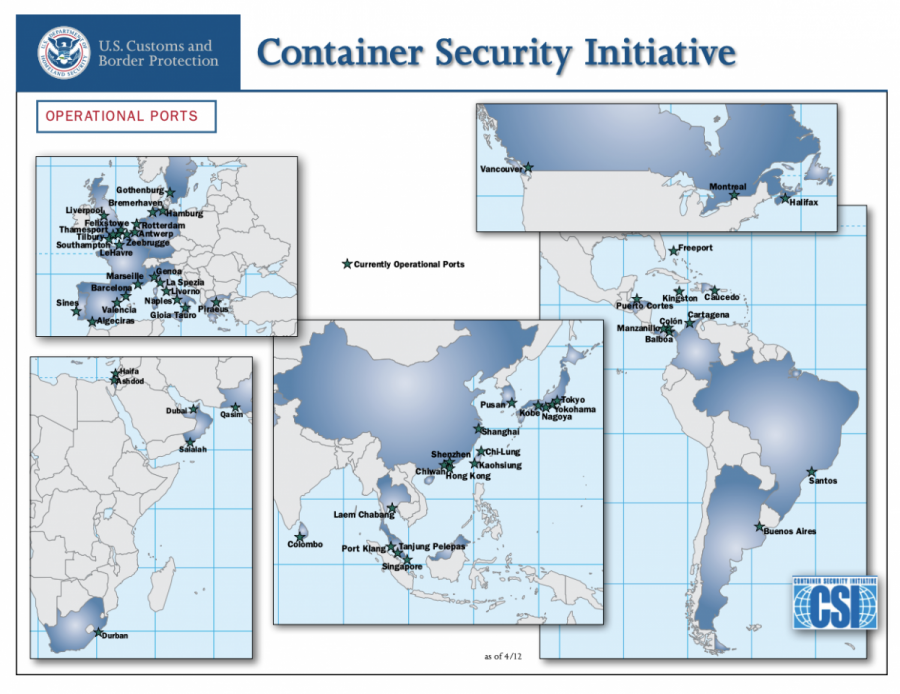

2. The Container Security Initiative (CSI)

Following the events of 9/11, the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection (CBP), a division of the Department of Homeland Security, reasoned that if the U.S. imports large volumes of foreign goods—and many of those goods emanate from a small group of large foreign ports—that security of cargo entering the U.S. could be facilitated by inspecting cargo at its foreign point of origin rather than waiting for the cargo to appear at our seaports. If CBP posted customs officials at a few of these large foreign ports, cargo could be inspected there before it is loaded and shipped to the U.S. It is not necessary to inspect all cargo, so the CBP officials do not inspect every container coming to the U.S. Rather, they look at cargo documents (bills of lading) for evidence of anomalies in the data: an unfamiliar shipper, inadequate description of the container contents, cargo from a shipper who has not been forthright in the past or has had its descriptions of cargo challenged, or also tips from other agencies to give special attention to a load of cargo.

At one level, the CBP can hold a container at the export terminal for verification of information on the bill of lading, and, in some cases, the entire container can have its contents removed for further inspection by U.S. customs agents. The objective of CSI is to resolve discrepancies at the point of origin for export cargo, but it has an added advantage because as questions are resolved overseas its movement once reaching a U.S. port is expedited: it is thus able to pass through the domestic inspection process expeditiously, decreasing dwell time (time that a cargo container is held on the arrival terminal waiting for clearance to be released into the domestic transportation network) upon arrival and sending it quickly to its recipient.

However, the objective from the start of the program was to reduce the chances of terrorists using the anonymity of intermodal cargo containers to hide weapons bound for America. Accordingly, three core elements describe the objective of the initiative:

- Identify high-risk containers. CBP uses automated targeting tools to identify containers that pose a potential risk for terrorism, based on advanced information and strategic intelligence.

- Prescreen and evaluate containers before they are shipped. Containers are screened as early in the supply chain as possible, generally at the port of departure.

- Use technology to prescreen high-risk containers to ensure that screening can be done rapidly without slowing down the movement of trade at the port of entry. This technology includes large-scale X-ray and gamma-ray machines and radiation detection devices.[6]

The CSI, as reported by CBP, now covers 58 seaports worldwide in Europe, Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Central, and South America. Over 80% of cargo from these areas is pre-screened before leaving the port of departure. In addition to CBP inspectors from the U.S. being stationed overseas, CSI reciprocal partner nations are similarly eligible to send their inspectors to the U.S. for export cargo headed to their countries.

Initially, the CSI was termed “The 24-hour rule,” meaning that cargo documents must be transmitted electronically to the CBP at the port of entry to the U.S. to permit adequate screening of the documentation before containers were landed there. However, as of April 1, 2003, the 24-hour advance notice was modified and now requires that documentation be provided to the port of entry 96 hours prior to the arrival of the vessel in port.[7] Clearly, the “screen door” has been transformed into a sturdy new barrier to illicit and questionable cargo entering via our busy seaports.

3. Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (C-TPAT)

As cargo screening has become more stringent not only in the U.S. but worldwide, safety has improved. But what about those shippers who move large volumes of predictable goods on a regular basis through the goods movement system? Does the system consider their unique needs when they move thousands of containers per year through the same seaports with similar types of goods contained? In response to this demand, the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection instituted C-TPAT in 2001 to facilitate goods movement by frequent importers of foreign-made goods. As the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection describes the program:

CTPAT is a voluntary public-private sector partnership program that recognizes that CBP can provide the highest level of cargo security only through close cooperation with the principal [sic] stakeholders of the international supply chain such as importers, carriers, consolidators, licensed customs brokers, and manufacturers. The Security and Accountability for Every Port Act of 2006 provided a statutory framework for the CTPAT program and imposed strict program oversight requirements.[8]

Importers described here by CBP can apply through the program to gain expedited approval of their goods entering the U.S.:

U.S. importers/exporters, U.S./Canada highway carriers; U.S./Mexico highway carriers; rail and sea carriers; licensed U.S. Customs brokers; U.S. marine port authority/terminal operators; U.S. freight consolidators; ocean transportation intermediaries and non‐operating common carriers; Mexican and Canadian manufacturers; and Mexican long‐haul carriers, all of whom account for over 52 percent (by value) of cargo imported into the U.S.[9]

The advantage to shippers is the speed with which their goods can pass through customs, but a reciprocal advantage accrues to CBP in that the cargo of the trusted shipper moves through the port of entry quickly, providing additional time for the agency to devote to non-standard cargoes entering the country. CBP assigns a Supply Chain Security Specialist from its agency to work with each C-TPAT importer to assist it in complying with U.S. regulations and to enable it to use the Free and Secure Trade (FAST) lanes at ports of entry. The program does not eliminate examinations by CBP, but these delays are minimized for companies in compliance. As it notes, by participating in the program, companies are eligible also to participate in other expedited entry programs such as the Food and Drug Administration’s Secure Supply Chain program.

Protecting Cargo and People

In a world where vast volumes of cargo move from one country to another, and where malicious actors can take advantage of that cargo flow to infiltrate weapons to target countries, vigilance is mandatory to screen out risks. As we have seen, the risks can come domestically as well as from afar, and statutes such as the MTSA establish a secure screening both for cargo and personnel who have access to it. The CSI and C-TPAT each have the objective of facilitating the screening process, some of it at foreign points of departure for goods bound for the U.S. Yet, since risky cargo is a small percentage of all imports, the C-TPAT provides an import route for frequent shippers who are willing to submit to advance scrutiny of their operations as well as their imports. The events of September 11, 2001, have created a long string of consequences for shippers, workers, and customs regulators, but the U.S. Congress has created a multi-faceted set of statutes and regulations to protect the American public from malefactors both here and abroad.

References

[1] Precursor legislation embodied in: the Safety of Naval Vessels Act of 1941, the Port and Tanker Safety Act of 1978 (later renamed the Port and Waterways Safety Act), and later the Omnibus Diplomatic Security and Anti-Terrorism Act of 1986.

[2] P.L. 107-295 (Nov. 25, 2002). Maritime Transportation Security Act of 2002.

[3] IMO. N.d. AIS Transponders: Regulations for Carriage of AIS. https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/AIS.aspx

[4] IMO. (15 Dec 2015). Regulation A.1006(29): Revised Guidelines for the Onboard Operational Use of Shipborne Automatic Identification Systems (AIS). https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/Safety/Documents/AIS/Resolution%20A.1106(29).pdf

[5] Campbell, J. (June 2017). The Seafarer’s Identity Document. Keesing Journal of Documents and Identity. P. 17

[6] U.S. Customs and Border Protection. May 31, 2019. CSI: Container Security Initiative. https://www.cbp.gov/border-security/ports-entry/cargo-security/csi/csi-brief

[7] American Shipper. (31 March 2003). Coast Guard Rules for 96 Hour Advance Notice Take Effect. https://www.freightwaves.com/news/coast-guard-rules-for-96-hour-advance-notice-take-effect#:~:text=Revised%20U.S.%20Coast%20Guard%20regulations%20regarding%20the%2096-hour,attorney%20in%20Washington%2C%20D.C.%2C%20in%20an%20industry%20advisory.

[8] U.S. Bureau of Customs and Border Protection. N.d. C-TPAT: Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism. https://www.cbp.gov/border-security/ports-entry/cargo-security/CTPAT.

[9] Ibid.