While passengers of this Zuiderdam cruise ship were exploring the small city center of Iceland, Akureyri, the Zuiderdam crew were undergoing a lifeboat safety drill. Source: Ted McGrath, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

19. Maritime Safety for Crews, Passengers, and Other Vessels

Author: Dr. James A. Fawcett, USC Sea Grant Maritime Policy Specialist/Extension Director (retired)

Media Contact: Leah Shore / lshore@usc.edu / (213)-740-1960

In this Ship’s Log article, learn about the protocols that the maritime industry has put in place to provide safety for our crews, passengers, and other vessels. Read below to learn about four of these important international maritime policies.

International Convention for Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS)

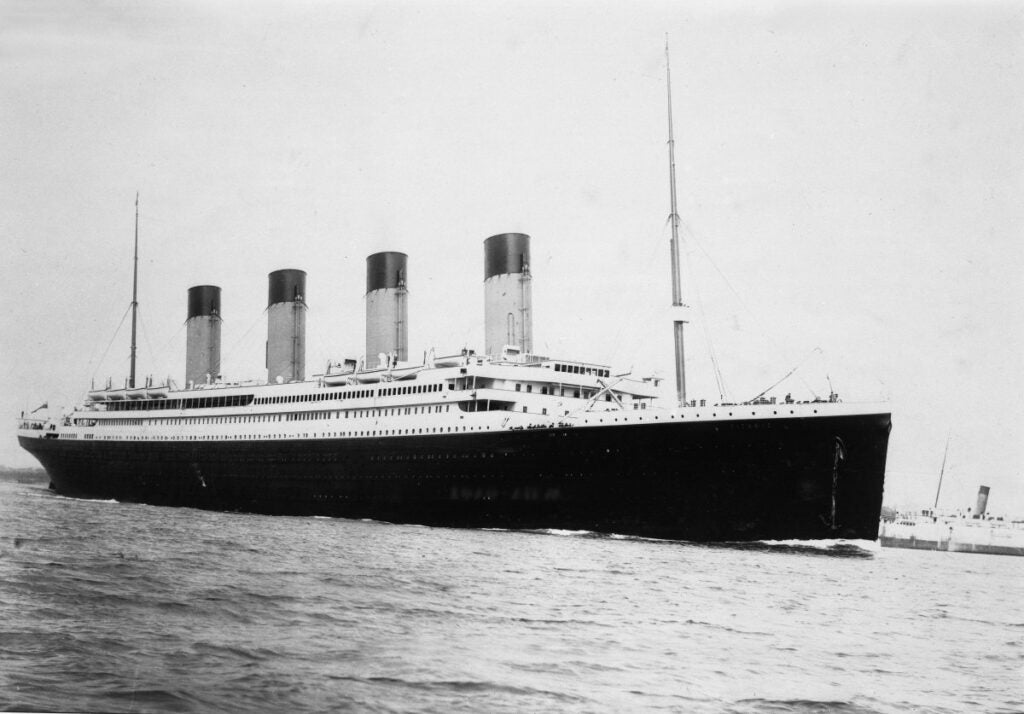

Disasters often bring us to our senses: the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, the Hindenburg fire in 1937, Chernobyl in 1986, or Fukushima in 2011. Notably, the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912, with the loss of 1,514 out of 2,224 passengers[1] and crewmembers, brings a chill to our imaginations when we think of the icy waters of the North Atlantic, inadequate lifeboats, and lack of preparation for a risky voyage through those iceberg strewn seas. So stunning was the public impact of the disaster on the maiden voyage of a ship reputed to be “unsinkable” with its new design including sixteen watertight bulkheads, that public opinion demanded something be done. Appointed by the British Lord Chancellor, John Bingham, 1st Viscount Mersey, led an investigation of the sinking, noting that the lifeboats were improperly filled (i.e. not fully filled), the ship was inadequately crewed, the captain failed to heed ice warnings, and the ship was traveling at 22 knots, too fast for such dangerous waters.[2]

With the publication of Viscount Mersey’s report, in 1914, the British Parliament enacted the first of what has emerged as a series of treaties, laws, regulations, and policies to provide for much-enhanced safety at sea. The first of these, the International Convention for Safety of Life at Sea(SOLAS), was a treaty that never actually went into force because of the outbreak of World War One. However, post-war the essence of the convention was so clearly necessary due to wartime sinkings that by 1929, it was enacted by the requisite number of seagoing states, becoming the international convention that remains in force today. It has subsequently been revised in 1948, 1960, 1974, 1987, 2011, and 2015.

If you have ever boarded a commercial vessel, you have experienced the provisions of SOLAS. For example, before leaving the dock, the crew will give instructions as to the location of the life preservers. Further, on a ship, especially a passenger ship, there will be a lifeboat drill where you are familiarized with your lifeboat station (the location to which you are to report when advised by the crew). But, the provisions of SOLAS now include many other aspects of safe sailing: specifications for construction of vessels; fire protection; radio communications; navigation safety; carriage of dangerous goods;[3] the International Safety Management Code (ISM Code) requiring inspections and audits of vessels and managers to ensure safe operation, a procedure that has also incorporated into SOLAS; and, most recently, the International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS Code), implemented in the aftermath of 9/11 and requiring security for both ships and the terminals in which they dock.

Not only does SOLAS consider the design of vessels, but also the management of both cargo and embarked passengers. In 2015, the SOLAS Container Weight Verification Regulation[4] came into effect to ensure that the actual mass of cargo in each container is calculated and provided to the carrier’s officers, permitting safe loading and stowage of cargo on container ships. Also, with the advent of global warming, the newest sections of the code now include standards for sailing in polar waters, integrating the International Standards for Operating in Polar Waters (the Polar Code). While the range of regulations may seem burdensome, memories of earlier disasters at sea provide ample justification for their application, and mariners realize their own lives depend upon implementation of the SOLAS rules.

Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGS)

Until the mid-19th century, maritime transportation and commerce were limited by the speed at which ships powered by wind could sail and maneuver. Some, such as the vaunted clipper ships in the latter part of the age of wind, were indeed speedy. However, the advent of the steam boiler and its use in maritime vessels caused unfortunate conflicts at sea. The trouble was that sailing ships were constrained in their forward progress by the direction of the wind, and to maintain their own forward advance, they were required to trim their sails and rudders accordingly. Yet, steam-powered ships could sail in any direction at will, and when the two ship types were close to one another, conflicts over which had the “right of way” were frequent.

In the 1840s, seagoing nations developed rudimentary rules for ship captains to use in negotiating these encounters. Unfortunately, the rules were generally applied on a national basis, so vessels from other nations were neither constrained nor its officers always aware of unilateral structures imposed by a single state. Over time, the rules found wider acceptance, although still imposed by each nation on its own. Some were adopted as standard practices by multiple states, while others stood as unique standards. Basically, the rules were expressed in three categories: standards over navigation lights on vessels and so-called “day shapes;”[5] standards over navigational and pilotage outside of inland waters of a nation; and sound and light signals (i.e. whistle and horn signals).

The 1960 revision of SOLAS included “International Regulations for Prevention of Collisions at Sea” as a component that continued in force until 1972 as guidance for mariners. However, in 1972, the entire convention was revised into a new entity and format as the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972 (COLREGS) that remains in force today. It divided the former standards into 41 new rules divided into six sections:

- Part A – General;

Part B – Steering and Sailing;

Part C – Lights and Shapes;

Part D – Sound and Light signals;

Part E – Exemptions; and

Part F – Verification of compliance with the provisions of the Convention.[6]

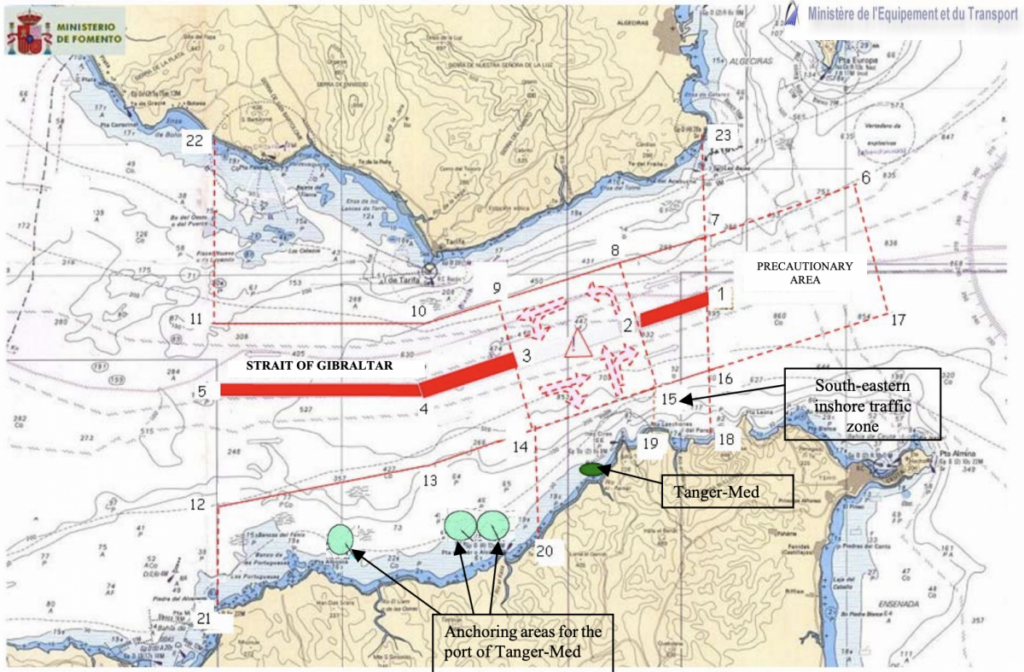

Among its innovations was a rule to prevent collisions in waterways defined by Traffic Separation Schemes.[7] Rule 10 provides guidance for vessels in or near traffic separation schemes instructing vessel masters as to safe speed, risk of collision, and vessel conduct near these areas. While the convention was adopted on 20 October 1972, it came into effect on 15 July 1977 when a satisfactory number of signatory states ratified it in their own legislative bodies. Implemented as a treaty, it provides worldwide guidance to mariners that the so-called “nautical rules of the road” will be consistent everywhere, providing a new level of safety to marine operations.

International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW)

Continuing its mission to standardize certification of marine operations, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in 1978 addressed the methods by which mariners were qualified for seagoing employment as well as the methods by which they operate the vessels on which they serve. In that year, the new International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW) was adopted and later ratified in 1984. It was significantly amended in 1995 and again in 2010 and ratified on 01 January 2012. Subsequent amendments in 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2018 have resolved and added details to the 2010 text.

The Convention is designed to rationalize the level of training and means of certification worldwide such that mariners fulfilling equivalent roles in any fleet of vessels would have similar training and certification, and be equally qualified to operate a similar vessel. Training and certification go hand-in-hand, and initial training must be augmented by additional training at intervals for seafarers to retain their licensure standing. Furthermore, the training regimens and certification processes must be reviewed and approved periodically. These requirements responded to claims that national qualifications for seagoing officers and labor were uneven and that a lack of adequate training and certification endangered the safety of fellow mariners when sailing in common waters.

Chapter VIII of STCW[8] specifies the standards for all officers in charge in a watchkeeping role as well as the ratings forming a part of the watch. Among the standards are that the officer in charge of standing a bridge or engine room watch shall remain at his/her station at all times during the watch; similar rules apply to all ratings (sailors serving under the officer in charge) who are part of the watch. Of the many details specified in Chapter VIII, required rest or sleep is critical. Watchstanders shall be provided with 10 hours of rest in a 24-hour period and, at a minimum, at least one rest period shall not be less than 6 hours in duration.

Fatigue of the bridge crew officers conning the vessel at the time was found as an aggravating factor in the grounding of the M/V Exxon Valdez on Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound, Alaska in March of 1989. Maritime unions representing both deck and engineering ratings have been influential in demanding that the IMO specify work rules such as those in STCW to protect the lives and safety of rated personnel, without which unscrupulous operators could demand unreasonable hours of labor from ratings. As in other occupations requiring vigilance during operations, the requirements of the Convention merely echo those regulations, but in a maritime context to promote the safety of crew and vessels.

International Ship and Port Security Code (ISPS)

After the 9/11 attacks on the US, there was a feat of the potential for terrorists to use a maritime vessel as a container either for smuggled contraband explosives or for terrorists in person in the U.S. or other maritime nations. At the urging of the United States, the IMO formulated and adopted the International Ship and Port Security Code (ISPS) as an amendment to SOLAS Chapter IX-2. It is divided into two parts: Part A specifies mandatory actions that must be taken by ports and ship operators to secure themselves; Part B contains recommended actions that can be taken to enhance security.

Not only was the 9/11 attack an important influence, but also an October 2002 attack by suicide bombers touched off a major fire on the 1,100-foot-long, French, ultra-large, crude carrier, M/V Limburg in the Gulf of Aden, resulting in a spill of 90,000[9] barrels of crude oil into the Indian Ocean. As stated by the IMO, the objective of ISPS is:

- establishment of an international framework that fosters cooperation between Contracting Governments, Government agencies, local administrations, and the shipping and port industries, in assessing and detecting potential security threats to ships or port facilities used for international trade, so as to implement preventive security measures against such threats[10]

ISPS is further intended to share information, encourage vigilance, provide methods for both ships and ports to increase their levels of security, and ensure that those methods are widely shared and implemented by ships and ports. ISPS is implemented in the U.S. by the Coast Guard at each seaport and by the Transportation Security Agency. Upon approaching a seaport or one of its marine terminals, we now find that those facilities are fenced, and that access is strictly limited to those having business within the enclosure. Furthermore, workers in the U.S. must now have a “Transportation Worker Identification Credential” or TWIC for access to these facilities.[11]

Conclusion

As international commerce has grown over the decades, it has become ever more imperative that parochial rules for vessel and personnel safety need to be improved. Accordingly, the IMO has taken responsibility for developing comprehensive rules that apply worldwide to secure maritime safety. While the four noted above are mainly concerned for the safety of humans and vessels, in a future Ship’s Log article, we will address the safety of cargo as it moves across nations and oceans.

References

[1] Mersey, Lord (1999) [1912]. The Loss of the Titanic, 1912. The Stationery Office.

[2] Butler, Daniel Allen (1998). Unsinkable: The Full Story of RMS Titanic. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

[3] Under the International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code (IMDG Code), incorporated into SOLAS.

[4] IMO. 2016. SOLAS Chapter VI, Regulation 2, paragraph 6.

[5] Day shapes are specific flags or literally shaped objects (a ball, cylinder, cone, or diamond) that are raised on a flag hoist of a vessel during daylight hours to signal an activity on the vessel that would be designated by a unique light array during nighttime hours.

[6] IMO. 1972. Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972 (COLREGs). https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/COLREG.aspx

[7] Traffic Separation Schemes exist in southern California in the Santa Barbara Channel between the Channel Islands and the mainland also in the southern approach to the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach in San Pedro Bay. See NOAA Charts 18746 and 18749.

[8] IMO. N.d. Standards Regarding Watchkeeping. STCW.6/Circ. 1, ANNEX, P. 132. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/torontobrigantine/pages/51/attachments/original/1436196906/03_-_STCW_Code_Section_A-VIII.pdf?1436196906.

[9] Equivalent of 3,780,000 gallons

[10] IMO. N.d. SOLAS IX-2 and the ISPS Code. https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Security/Pages/SOLAS-XI-2%20ISPS%20Code.aspx

[11] The credentials are issued jointly by the US Department of Homeland Security, Transportation Security Agency, and the US Coast Guard. See https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/privacy_pia_twic09_0.pdf and https://www.dco.uscg.mil/nmc/twic/.