Soaring over King Tides

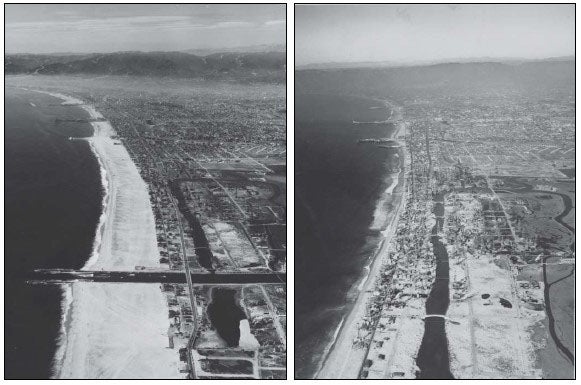

On the morning of January 22, 2019, I hopped on board LightHawk volunteer pilot Bill’s single-engine plane to see what the morning’s 6.8-foot King tide had in store for the Southern California coast. Immediately after take-off, we were struck by the immense development of our urban coast: ports, freeways, apartments, golf courses, houses, industrial facilities, parking lots. As we hooked south from Torrance airport, we saw a dense mix of human development and natural features. The fragmentation of Los Cerritos Wetlands, the channelized LA River, the relatively natural Seal Beach National Wildlife Refuge, and the engineered community of Naples illustrated dramatically how human intervention and ingenuity disrupt natural systems – still visible but greatly disturbed.

When it comes to understanding how our coast changes and thinking about a future with greater rates of sea-level rise and coastal change, a unique opportunity comes in the form of King Tides. King Tides are the colloquial term for the most extreme high tides of a year. These perigean spring tides occur as the result of astronomical phenomena associated with the position of the earth in relation to the sun and moon and their subsequent gravitational pull. These natural and predictable occurrences (although infrequent, roughly twice a year) provide insight into present vulnerabilities from the higher water levels and a future where higher water levels become normal conditions.

I was invited by Surfrider Foundation and LightHawk as we soared over the coast with Arielle Duhaime-Ross, VICE News Tonight’s environment and climate correspondent, as part of a national collaboration to catalog and observe King Tides. More than 20 flights covered key areas along the Pacific and Atlantic coastlines to promote awareness of coastal vulnerabilities and provide insight for present and future coastal management.

Because of the active and dynamic nature of California’s coastal environment, true risk comes in the form of high tides and higher sea level, in combination with swell and/or storm events (i.e. rain). It is when these factors align, say a significant swell and higher tide, that California’s coast experiences substantial erosion and flood vulnerability. Although the recent significant swell had subsided a few days before, the higher tide gave a glimpse of what sea level rise might look like. Hooking back northward around San Pedro brought other natural hazards to the forefront. From Sunken City to White Point and Portuguese Bend, landslides of the past and the potential for them in the future was perceptible. Although those natural hazards were not associated with climate change, seeing whole sections of bluff slump and what impacts these have on coastal communities demonstrate dramatically how climate change will affect our coastal areas.