September 2020

USC Equity Research Institute, Committee for Greater LA, and UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs

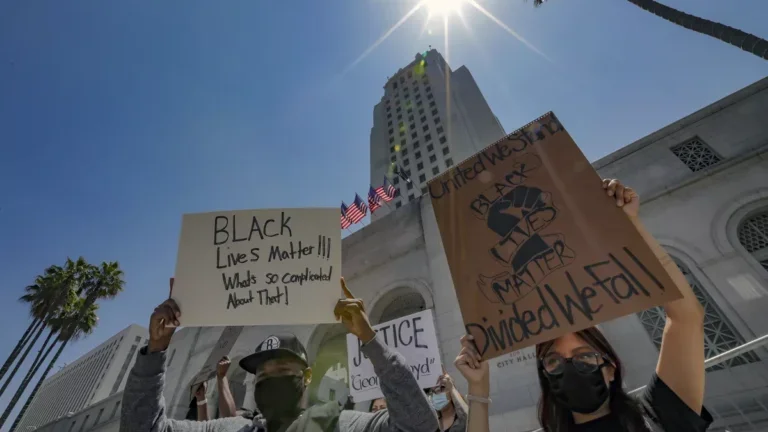

Prior to the stay-at-home public health directive, civic boosters promoted Los Angeles as a metropolis that was confronting its problems and making progress. Local and state governments enjoyed budget surpluses, unprecedented investments were committed by Angelenos to respond to homelessness, and access to health care and high school graduation rates were at historically high levels, while unemployment and crime rates were at celebrated lows. But behind this glossy view of Los Angeles, a closer look at the data would have revealed a very different reality, where decades of structural and systemic racism resulted in significant social, economic, and racial inequality. Just a few months into a global pandemic, the cracks in the broken systems have become gaping holes, widening each day. Today, the calls for systemic change are loud, consequential, and urgent.

Early in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, ten foundations wisely convened a diverse group of community, civic, non-profit, labor, and business leaders to identify the systemic issues emerging from the crisis and to offer up a blueprint for building a more equitable and inclusive Los Angeles. Their past philanthropic work had made it clear that Los Angeles was becoming increasingly inequitable, and they feared the acceleration of disparate impact centered on income and race. The Committee for Greater LA was formed, and for the past five months, it has steered the analytical work completed by two of L.A.’s leading institutions, UCLA and USC, supported by a team of consultants. The report that follows reflects our discourse, analysis, and discovery.

Download report

Media Mentions

No going back to racist past, L.A. civic leaders say of post-COVID future

Doug Smith, LA Times 9/9/20

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Editorial: COVID exposed Southern California’s inequities and injustices. Now it’s time to fix them

LA Times Editorial Board 9/10/20

(Photo / Los Angeles Times)

Report Highlights

The impacts of COVID-19 were initially felt in wealthier, white communities, as some of the early cases resulted from international travelers and/or because these communities had better and early access to testing and health care. As time has gone on, Latinos are now carrying the greatest weight of infections.

The death pattern from COVID is also sharply racialized. The age-adjusted death rates per 100,000 for African Americans and Native Americans is double that of whites (with many Native American cases possibly misclassified or underreported), and with the Latino rate slightly higher than that, and the Pacific Islander rate four times as high.

A racialized pattern also persist for workers in “essential” and “high risk” occupations. Around 30% of Black, Latino, and immigrant Asian workers in Los Angeles County fall in this category while the figure is a striking 38% for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. By contrast, only 17% of white individuals are in essential, higher risk work. There is also an overrepresentation of Latinos, African Americans, and Native Americans in what is considered “non-essential” but close proximity work, where there were sharp initial lay-offs and where we have seen a grudging start-stop rebound. The combination means that workers of color have been both more likely to be stressed by job loss and more likely to be showing up for dangerous employment.

Seniors need the most support because they are particularly vulnerable to the pandemic. Across L.A. County, the share of seniors of color are far more likely to live below 150% of the poverty level than white seniors.

The share of people of color making less than $15 an hour is much higher than it is for whites. When controlling for education, these stark racial disparities are wider.

The unemployment pain and the resulting economic stress has been unequally distributed, as women have been hit harder than men, the young much harder than those who are older, and Black workers far harder than every other ethnic group.

Being on the other side of the digital divide is a particularly troublesome situation when COVID-19 quickly developed into a pandemic and students were sent home and distance learning ensued. While only 13% of white kids found themselves lacking high-speed internet and a laptop or desktop in the household, that figure was 37% for Black children, 39% for Latino children, 25% for Pacific Islander children, and 24% for Native American children.

COVID-19 is also particularly concerning for seniors living alone because living alone is a risk factor, as it can create a lack of access to resources and social support. In Los Angeles County, more Black seniors are living alone (without family members and not in assisted living) than any other group.

Homelessness in Los Angeles County has risen from its already shocking pre-COVID-19 levels, disproportionately impacting people of color. While Black Angelenos represent about 8% of the total County population, they constitute over a third of the population experiencing homelessness. Moreover, the share of Native Americans who are homeless is roughly five-fold their share of the County.