2025 REU Program Intern Elyssa Baker conducts fieldwork in the Isthmus Cove near the Wrigley Marine Science Center. She collects mucilage, the slimy rich outer coating that helps protect giant kelp (Anya Jiménez/USC Wrigley Institute).

From Curiosity to Kelp Forests: My Summer in the Levine Lab

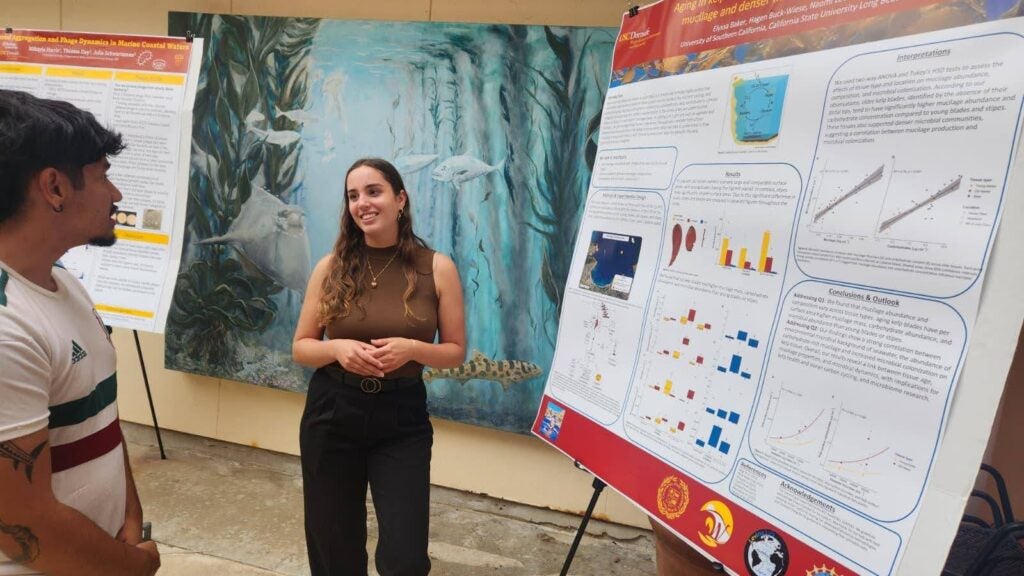

My name is Elyssa Baker, and I’m a rising senior studying environmental science and policy at California State University, Long Beach. This summer, I had the privilege of joining the USC Wrigley Institute’s Research for Undergraduate (REU) program, an experience that completely transformed the way I see myself as a scientist.

Visiting coral reefs and mangrove forests shaped a large part of my childhood as someone with Puerto Rican heritage. I fell in love with these ecosystems, but what became evident as I became more aware of my environment and as time passed was that climate change, pollution, and coastal development are eroding their health. When I moved to Southern California, I found the same story unfolding in kelp forests and estuaries. I wanted to protect these places, but while I had worked on environmental justice and sustainability projects as an undergrad, I had never done hands-on marine research.

That’s why I applied to the REU program. It offered the opportunity to design and carry out my own research project, build my field and lab skills, and collaborate with scientists who share my passion for making science accessible and applying it to develop effective policies to meet environmental and conservation concerns.

I had the honor of working in the Levine Lab under postdoctoral scholar Dr. Hagen Buck-Wiese, where I was introduced to a world I’d only read about. Before starting my main project, I contributed to a study on the cell density of evolved phytoplankton strains, part of a research collaboration with a lab in Australia. It was my first real taste of marine lab work, sharpening my technical skills and preparing me for what was next: investigating one of the ocean’s great climate allies, giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera).

During one program seminar my mentor gave, he implied something that stuck with me: if you care about coral reefs, study how algae can help maintain the ocean’s ecosystem balance at the face of climate change.

Knowing this, I pursued my research project on giant kelp with full enthusiasm. Giant kelp is a huge brown algae that builds underwater forests along our coast. These forests are hotspots for marine biodiversity, nutrient recyclers, and, maybe most exciting, powerful carbon sinks.

We wanted to know: What helps kelp resist breaking down and keep storing carbon for so long?

One possible answer lies in its slimy outer coating, called mucilage. Mucilage is a carbohydrate-rich layer that, much like the mucus in our own gut, might protect kelp from decay by bacteria and environmental stress. To study this, we designed a project comparing young, intact kelp blades with older, disintegrating ones, as well as kelp stipes (the “stems”). Out in Isthmus Cove near the Wrigley Marine Science Center we scraped and collected mucilage from the kelp blades and stipes, and preserved subsamples in formaldehyde for microbial counting with a flow cytometer. We photographed each blade to measure surface area, kept our samples on ice, and brought them back to the lab for more analysis. In the lab, I learned a whole new skill set from extracting total carbohydrate concentration from algae to growing Vibrio bacteria in alginate cultures to extract their enzymes and use them to measure this carbohydrate in my sample.

Our results showed that older kelp blades had more carbohydrates in their mucilage, and more microbes, than younger blades. We also found that areas with higher bacterial abundance in the surrounding seawater had more mucilage carbohydrates. This points to a tight link between kelp age, its mucilage composition, and its microbiome. In short, as kelp ages, its mucilage changes in ways that could affect its health, its microbiome, and its role in carbon cycling.

Although this summer’s findings were fascinating, the discoveries weren’t just about kelp, but also about me. At the start of the summer, I had zero marine field experience. I didn’t know how to use a clean bench or what a flow cytometer was. By the end, I was designing experiments, running assays, analyzing data, and presenting my findings. I learned that science is as much about persistence and curiosity as it is about technical skill.

This experience gave me far more than research results, it gave me confidence. Now, I feel ready to take the next step toward a career that blends marine research and conservation. I’m deeply grateful to the Levine Lab, my mentor Hagen Buck-Wiese, and Dr. Diane Kim for their guidance and support. I am leaving this experience inspired and full of ambition to tackle what is ahead in becoming a scientist.