Students in Test Plot elective course Arch 546, USC Wrigley Institute for Environment and Sustainability staff and affiliated faculty, and volunteers planted a plot on Catalina Island in the USC Wrigley Marine Science Center’s “Green Ravine”. (Nick Neumann/USC Wrigley Institute)

USC Wrigley Institute, School of Architecture collaborate to test sustainable landscape design methods

The Wrigley Marine Science Center (WMSC), USC Wrigley Institute for Environment and Sustainability’s satellite campus, is situated in a unique location that makes it ideal for research and educational activities–but that location also poses some special challenges for the campus’s operational sustainability. Now, a collaboration between the Wrigley Institute and USC’s School of Architecture is providing students with hands-on research experience while also helping to solve one of those sustainability challenges.

WMSC is situated at the edge of Big Fisherman Cove, a “no-take” marine protected area (MPA) where human activity is regulated to conserve biological diversity and provide a sanctuary for marine life. The cove is also an Area of Special Biological Significance (ASBS), meaning that it is heavily monitored by the state to ensure that water conditions remain pristine.

Given that the facility is in an ecologically important location, a significant part of Lauren Oudin’s role as the Wrigley Institute’s scientific operations manager is to implement best management practices to ensure that the cove continues to meet state requirements, despite the busy schedule of activities that take place at WMSC.

Beyond ensuring sustainable operations, Oudin and the Wrigley Institute team face another significant challenge: Catalina Island has abundant naturally occurring metals that bind to the particulates in the native soils. Especially when the campus experiences heavy rainfall, water that flows through WMSC’s Green Ravine (a rocky culvert that cuts vertically through the middle of campus) can carry those sediments down to the cove, potentially affecting water quality in the MPA and ASBS.

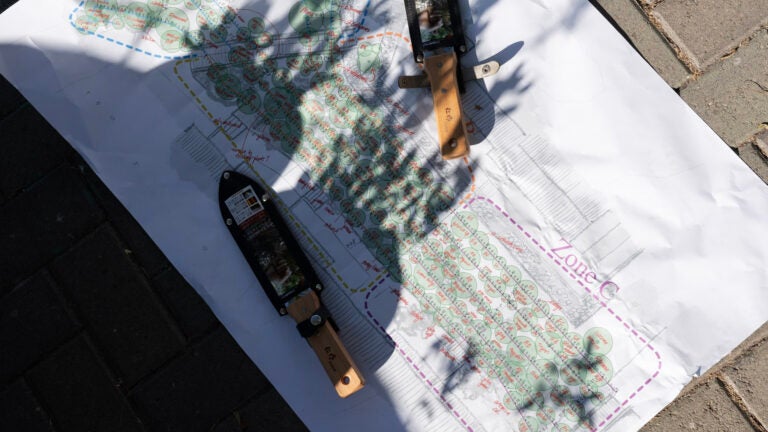

That’s where Test Plot, a community land-care initiative under the Landscape Architecture + Urbanism program at the USC School of Architecture, comes in. This fall semester, the Wrigley Marine Science Center’s Green Ravine was the focus of an experimental, project-based Test Plot class led by associate professor and landscape architect Alexander Robinson. Throughout the semester, Test Plot students surveyed the site, conducted interviews with stakeholders, and co-designed ways to reinvigorate the Green Ravine with native plants donated by the Catalina Island Conservancy to help address the challenges facing the campus.

“A lot of times, wild plants don’t necessarily fit the sanitized ideals of what’s considered beautiful. In the quest to expand more drought tolerant and native plants, we really need community buy-in,” said USC environmental studies (ENST) student Olivia Heffernan. “It’s important to bring people in, have them engage with wild plants and be around their natural beauty, and learn to appreciate them.”

Over the course of three days in November, more than 30 volunteers came together to install the plot in WMSC’s Green Ravine. The first test plot on Catalina Island, the ravine is now home to 175 native plants and two new rock check dams. These improvements are designed to slow down the flow of water and collect soil sediment, thereby filtering stormwater before it reaches the ocean in Big Fisherman Cove and encompassing MPA and ASBS.

“The rock check dams will alter the hydrology of the area to slow the water down, reduce erosion, and also have more linger time with the water to interact with the plants and hopefully increase the downstream water quality as well,” said Jeremy Joo, Test Plot intern and third-year graduate student in USC’s Master of Landscape Architecture program.

Joining the planting and dam building project were Catalina Island Conservancy’s conservation horticulturist Cayman Lanzone and restoration technician Lauren Rocheleau, who worked closely with the Test Plot team to develop the planting palette. They also provided equipment during installation.

“With this test plot, we not only started to restore this part of the Green Ravine and achieve the stormwater quality requirements that the Wrigley Institute was so interested in, but we also connected the Wrigley Institute with the Catalina [Island] Conservancy in a way that’s never been done before,” said Alexander Robinson.

Among the native plants that were chosen for the Test Plot is the spiny rush, a sharp-pointed plant with a deep taproot usually found along river beds on the island and known for its ability to reduce erosion rates.

“It’s really interesting to see how some of these small landscape manipulations are really changing things,” said Lauren Oudin. “Now we see that the area is retaining more water because of this riparian plant. It’s recruiting, and it’s growing.”

To Oudin’s surprise, the Green Ravine is changing faster than expected since the installation of the Test Plot. Not only is there an increase in the species of flora, but also in the types of fauna found in the area. Given that water can be a limited resource on Catalina Island, Oudin anticipates seeing animals such as frogs and dragonflies gravitate toward ponding water in the ravine as they did during 2022’s heavy rainfall season.

As the Wrigley Marine Science Center’s landscape continues to transform, in part due to the installation of the test plot, Oudin’s team and environmental studies faculty Scott Applebaum and Andres Sanchez plan to monitor and quantify the changes.

“One of the bigger, overarching goals of our work is to increase biodiversity. We’re starting to see more species remain here longer, especially in the ravine,” said Oudin. “Our next step is to hopefully get more students out here to monitor the changes. There’s a lot of great opportunities for our environmental studies students to get out in the field, get their hands dirty, and make exciting observations.”

In the News