Overlooking Capistrano Beach in Dana Point, CA. Photo by Jeri Koegel, Flickr Creative Commons

A Battered Beach: Revealing the Past and Planning for the Future

Earlier this month, Capistrano Beach (locally known as Capo Beach), a community located in the city of Dana Point within Orange County, California, experienced damaging storm surge along its coastline. Over the years, strong wave events like this one have revealed a long history of battling the ocean. Waves have revealed objects like an engineered seawall made of crushed cars and bits of tile from an old beach club pool, evidence of past attempts at keeping the water at bay. As this beach continues to be threatened by high tides, powerful waves, and rising seas, the community grapples with how to preserve their historic beach while adapting to the challenges of climate change.

The History of a Battered Beach

Throughout the 20th century, the narrow stretch of land at Capistrano Beach has held a large historical and personal significance to its surrounding communities. As far back as the 1930s, the beach attracted beachgoers and tourists who flocked to the Capistrano Beach Club, recreation facilities, and its nearby pier. Starting in the 1950s, the beach became a hub for the thriving Southern California surf scene. Additionally, a walking path was constructed in the early 1900s that connected Capistrano Beach to Doheny State Beach, a landmark that is widely utilized to this day.

In addition to its heritage as a recreational landmark, Capistrano Beach has a history of losing battles with the region’s climate. For years, repeated wave action eroded the foundation under the Capo Beach pier. Unfortunately, in 1964, severe wave damage finally crippled the pier and it was condemned. Similarly, the Beach Club was badly damaged by storms throughout the 50s and 60s and in the late 1960s, was demolished.

In addition to its heritage as a recreational landmark, Capistrano Beach has a history of losing battles with the region’s climate. For years, repeated wave action eroded the foundation under the Capo Beach pier. Unfortunately, in 1964, severe wave damage finally crippled the pier and it was condemned. Similarly, the Beach Club was badly damaged by storms throughout the 50s and 60s and in the late 1960s, was demolished.

Land throughout the San Juan Watershed, which feeds into Capo Beach, became heavily developed throughout the latter part of the 20th century. As homes and infrastructure were built, and more bodies of water became channelized (straightened and cemented), the flow of sediment from the watershed to the outfall at Capo Beach was severely disrupted. By 1991, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers estimated that the flow of sediment had decreased by 20-30% since 1900. The already narrow beach was now cut off from its sediment supply and began to erode more rapidly from wave action and storms. In the 1980s, Orange County acquired the beach and surrounding land. They improved the area by building restrooms and recreation facilities, including a basketball court nearly at the water’s edge, and underwent extensive beach replenishment. Beach replenishment means trucking in sand from other locations.

Increased Storm Damage Encourages Efforts to Improve Beach Resiliency

The beach provides a buffer between waves and the infrastructure in Capo Beach, absorbing wave energy and preventing storm damage. As the beach eroded, that protective barrier was slowly lost, and the park started to experience more damage during large storms. Throughout the years, the county added various hard protective measures in order to armor the park infrastructure including rock revetments (barricades), geotextile sandbags, and most notably a large timber seawall. However, while the seawall protected infrastructure against high waves, it further disrupted the sediment supply, leading to increased erosion and an even narrower beach.

An El Niño event in 2015-2016 caused record high water levels and extreme waves. Despite a sandbag revetment, the wave action caused significant erosion at both ends of Capo Beach, decaying the parking lot and sidewalks and depositing sediment throughout the park. In 2018, storm surge caused the beach-adjacent boardwalk to collapse from erosion and destroyed the basketball court and restrooms. By the summer of 2019, shoreline erosion and wave runup badly damaged the storm drain outfall at Capo. In order to protect the threatened stormwater treatment system and the walking path, the county installed 150 feet of sandbags along the beach.

The most recent storm event at Capo Beach occurred in early July 2020 and coincided with a high tide to produce dangerously high water levels. The storm surge destroyed the sandbags that had been installed the previous year, cracked the concrete and the asphalt in and around the parking lot, badly damaged the seawall, and nearly brought down the entire beach walking path between Capo and Doheny Beach.

In the aftermath of this July storm, the county began to relocate sand from the parking lot back on the beaches and started an effort to completely remove the damaged seawalls. During all of these events one point has been made increasingly clear: patchwork attempts to armor the beach from erosion and storm surge are not a sustainable long term solution.

A Key to Long Term Solutions: Understanding Sea Level Rise

Sea level rise has been a large component of the increasing erosion and narrowing stretch of beach experienced at Capo. In the last century, the mean sea level on the California coast has increased by nearly a foot in some areas, and the changing climate has exacerbated the frequency and intensity of events like El Niño. As the sea level continues to rise, and even accelerate, homes and infrastructure will become progressively more at risk. Some individual homes have built protective structures including revetments, seawalls, sandbags, and rip rap. However, the California Coastal Commission is responsible for approving such armaments, and access to these grants are competitive. Additionally, as the repeated storm damage at Capo Beach has proven, these additions are merely short-term solutions.

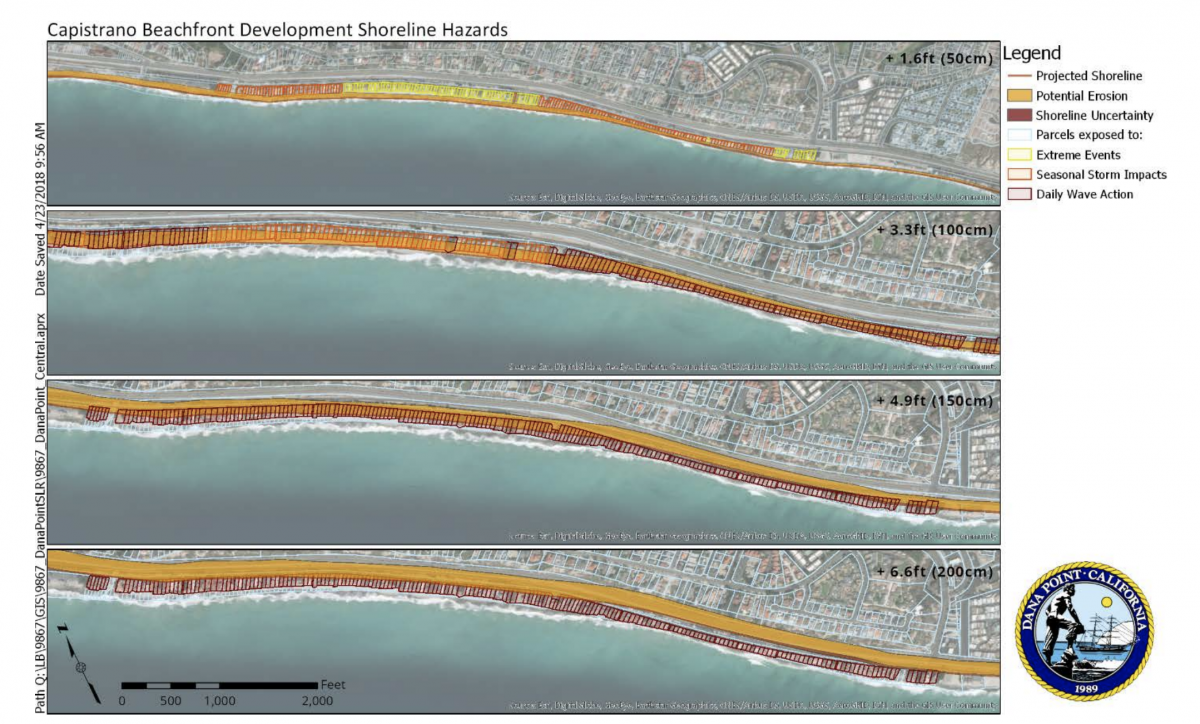

The Coastal Storm Modeling System (CoSMoS) was developed by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) to predict flooding along the California coast under various sea level rise scenarios. The CoSMoS findings at Capo Beach demonstrate the extreme hazards of sea level rise. For example, with a 1.6 feet increase in sea level, the beach would become nonexistent in front of hard shoreline protection, and frequent overtopping of infrastructure protecting the parking lot would occur. Over half of the properties in the surrounding developments would experience significant seasonal erosion. With 3.3 feet of sea level rise, over 130 properties in the Capo Beach developments would be flooded, and there would no longer be areas of dry beach. With 4.9 feet or more of increased water levels, all existing development in the Capo Beach community would likely be flooded. Additionally, CoSMoS does not take into account the massive shoreline loss at Capo Beach from the 2015-2016 El Nino event, and therefore could severely underpredict erosion and flooding in these scenarios. Current worst-case scenario projections as published by the City of Dana Point show up to 10 feet of sea level rise by the end of the century.

The City of Dana Point has recognized the severity of these sea level rise projections and the residents of Capo Beach have made clear their concerns of losing their beloved beach. The challenge now becomes how to reconcile the recreational and sentimental value of the beach, while adapting appropriately to the imminent environmental threats.

The City of Dana Point Sea Level Rise Vulnerability Assessment was published in October of 2019 and outlines possible strategies for adapting to these challenges. The document’s first suggested step is a large beach replenishment effort to restore the beaches at Capo and Doheny, as well as in front of the Capo Beach developments. However, as shown throughout Capo Beach’s history, and especially with increasing storm action, beach replenishment alone may not be sustainable in the long term. Another proposed plan in conjunction to replenishment is to create a hybrid dune protection system. This would consist of adding hard protection -including stone, cobble, and geotextile fabric- under a rehabilitated vegetated dune. A system like this would provide the hard protection necessary to protect against storm surge while allowing sediment to accrue and prevent further erosion. Finally, the most extreme adaptation method suggested is to retreat. This could be a daunting task for the hundreds of coastal properties in the developments surrounding Capo Beach. However, an initial and easier step to consider could be to remove the beach parking lot, allowing the beach to widen while creating more area for recreation and a wider buffer to absorb wave energy.

Opportunities to Adapt Through Community Collaboration

Unfortunately, Capo Beach is not unique in the challenges posed by climate change. Cities all across Southern California are grappling with how to adapt to sea level rise and extreme events. Fortunately, a regional effort called AdaptLA has allowed cities and organizations across Southern California to communicate and collaborate on adapting to these challenges so that no one has to navigate climate change alone. Led by USC Sea Grant, AdaptLA is a network between scientists and local coastal jurisdictions that strives to establish a community of practice by engaging collaboration and increasing the use of the best available science in planning efforts. AdaptLA provides tools like CoSMoS (the engine that provided sea level rise projections for Capo Beach) and resources on how to use them in order to inform local coastal adaptation planning efforts. Cities like Capo Beach are able to tap into the innovative network and scientific resources of AdaptLA to collaborate with other municipalities that may be facing similar challenges. As a result, many cities are making significant progress in integrating climate change considerations into their existing planning mechanisms and evaluating potential strategies for adaptation along the coast.

As storms continue to batter California’s coast and impact beaches and critical infrastructure, mitigating vulnerability across Capo Beach will likely require a dynamic implementation of many pathways of adaptation. Future planning considerations will need to include preserving the historical, recreational, and sentimental value of Capo Beach while addressing the extreme conditions that are possible under CoSMoS predictions. Additionally, history provides the valuable lesson that short term, reactionary solutions are not sufficient when planning for sea level rise at Capo Beach. Instead, preserving the beach and protecting nearby properties in the face of sea level rise will require a long term, proactive approach. Learning from history while utilizing innovative resources such as AdaptLA and CoSMoS projections can help Capo Beach identify common challenges along the coast and collaborate with cities on planning efforts to preserve this beautiful, historical beach amid a changing coastline.