New Findings Suggest that the Removal of Sea Urchins Result in Helping Kelp Forest Ecosystems

USC Sea Grant-funded research recently concluded a decade-long study on determining the effects of reducing sea urchin density in efforts to restore kelp forests in Southern California. Their results were recently published in the April 2021 issue of the Marine Ecology Progress Series. Many years, collaborations, and publications later, along with an unexpected curveball halfway into the study, the researchers conclude that drastically reducing sea urchins results in restoring healthy kelp forest ecosystems.

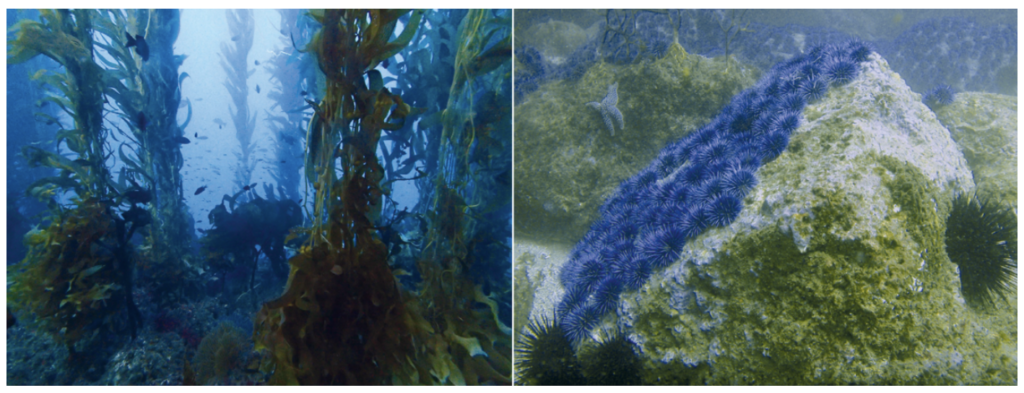

Beginning in 2012 with initial funding from USC Sea Grant, the Vantuna Research Group at Occidental College in Los Angeles teamed up with The Bay Foundation on this project to study the area of the Palos Verdes Peninsula, just north of Long Beach, CA. Kelp in this region, precisely Giant Kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera), is known as a foundation species that creates an ecosystem for over 700 species and supports high-value recreational and commercial fisheries. Nearly 25 percent of marine organisms in California depend on this ecosystem throughout their life, further revealing the significance of this coastal species.

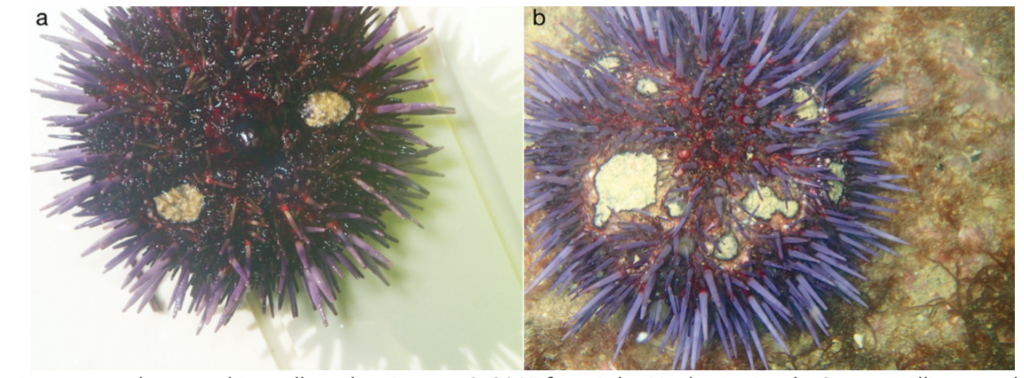

One of the most significant causes of kelp forest loss in this area of Southern California is from overgrazing by purple sea urchins (strongylocentrotus purpuratus) and red sea urchins (Mesocentrotus franciscanus). This overgrazing commonly leads to “urchin barrens,” areas of bare rock formed when large amounts of sea urchins graze entire kelp forests. In turn, this often reduces fish and invertebrate species who depend on the kelp forests, causing catastrophic ecological impacts and severe economic disruptions to our rocky reefs. Although sea urchin predators can usually control sea urchin grazing, many of these species (like otters) have been overharvested or killed by disease, despite even recent ecosystem-based management efforts in areas such as the Marine Protected Areas.

This project sought to analyze the effectiveness of culling (removing/replacing) sea urchins for restoration efforts by studying twelve sites–eight urchin barren sites and four kelp forest sites–every year for a decade from 2011 to 2020. Four of the urchin barren sites were monitored for restoration by culling purple sea urchins (they left alone red sea urchins as these are economically valuable and currently not overabundant). The other four barren sites were used as a control, and the four kelp forest reefs were used as kelp forest reference sites. Promising findings from the first three years of this research were highlighted by USC Sea Grant back in 2013; however, after this, mother nature unexpectedly changed the course of this project.

Halfway through this study, between 2014-2015, a large mass of unusually warm ocean water devastatingly affected the coast of Southern California, a natural event known as “the blob”. During this time, both red and purple sea urchins were found at the Palos Verdes Peninsula with black-ring disease, a deadly bacteria infection, killing a majority of sea urchins within the project sites and ultimately impacting the entire study.

Instead of stopping the experiment, the project team shifted their study to observe how urchin barren sites recovered after the event compared with the kelp forest reference sites. It was found that the drastic reduction of sea urchins in barren sites led to the restoration of the kelp forest and that all species (including benthic cover, algae, fish, and marine invertebrates) returned to healthy conditions within six months. Even damaged red sea urchins returned healthily and more abundantly. Further, these conditions remained stable throughout the remaining five years of the study. The above observations helped gain insight into what happens when sea urchins are removed, such as from culling urchins for restoration efforts. The study concluded that kelp restoration through sea urchin culling essentially mimics the mass mortality events of sea urchins.

The findings of this study suggest that removing purple sea urchins can produce similar declines as seen in the 2014-2015 mass mortality event, and it may be valuable to consider culling as a management tool to restore kelp forest communities rapidly. In addition to supporting healthy ecosystems of kelp forests, this recommendation may benefit economic and fishery interests as restoring kelp forests result in the return of precious commercial and recreational fisheries species. Additionally, the study recommends that by not removing the red sea urchins, the restored kelp forest will provide a more significant food source and lead to increased red sea urchin production for the commercial fishing industry.

Following the study’s conclusion, the restoration of kelp forests along the Palos Verdes Peninsula has recovered to the highest aerial amount covered in nearly 80 years, and several fish species have significantly increased in abundance and size. The researchers further conclude that in addition to restoring kelp forests through the reduction of sea urchin density, improving water quality and the protection of sea urchin predators can help prevent future urchin barrens.

Publication Citation:

Williams JP, Claisse JT, Pondella DJ II, Williams CM and others (2021) Sea urchin mass mortality rapidly restores kelp forest communities. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 664:117-131. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13680