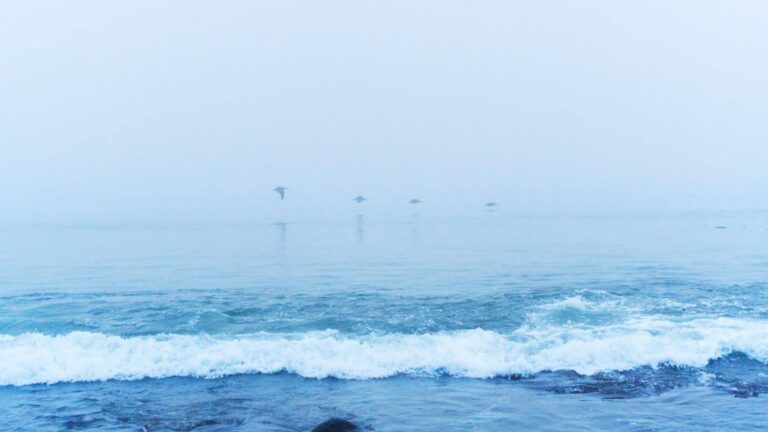

Brown pelicans flying over the water with limited visability. Image courtesy of Arian Tomar.

Fog, Filmmaking, and the Future of Kelp

It’s 4:30 am. I wake up, my mind already racing. Is everything packed? Did I forget anything? Is it going to be cold? I check the weather. 45 degrees. Not great. Not bad.

It’s 4:40. What’s in the fridge? I scan its blank interior for anything appetizing this early in the morning. I close the door, defeated. I should’ve gone grocery shopping.

It’s 4:50. Time to leave. I turn off the kitchen lights and I’m out the door.

It’s 5:30. I’m halfway to my destination, flying up the Pacific Coast Highway in the thickest fog I’ve ever seen. “This will clear up when the sun comes out,” I think to myself.

It’s 6 am. I finally feel awake. With my destination moments away, I think to myself: I can’t believe this is my job.

I’m parked, counting down the minutes to first light, expecting a beautiful sunrise, the feeling of the sun on my face, an escape from the cold, and – this is what I see.

It’s beautiful in its own way, but it certainly isn’t the sun-kissed beach I imagined on my hour-long drive. I laugh to myself. This is documentary filmmaking, and though I feel foolish, I know I’ll make the most of this. I can’t see more than 100 feet past the beach because of the fog, and I take a moment to reflect, enjoying the sound of crashing waves and the scent of salt in the air. How did I get here?

I’m Arian Tomar, a documentary filmmaker and film production student at the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California (USC). And I love nature. Growing up in Minnesota, I was surrounded by it, and, as I got older, I fell in love with science because it helped me understand the natural world around me. This fall, I worked with USC Sea Grant as an intern to share a cutting-edge science story about selective breeding kelp research. USC Sea Grant Program is part of the national network of 34 programs in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Sea Grant College Program. USC Sea Grant is a federal-university partnership that integrates research, education, and outreach on marine and coastal topics, such as the selective breeding kelp research project I was working on this fall.

Selective breeding is a common agricultural practice that takes domesticated individuals and makes them more fit for human use. Sweeter fruits, more resilient crops, and seedless watermelon are all the results of selective breeding in agriculture.

The research project, led by Sergey Nuzhdin (USC), Scott Lindell (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI)), Amalia Almada (USC Sea Grant), and Joshua Reitsma (WHOI Sea Grant), seeks to advance selective breeding efforts for kelp, which has tons of applications in products like toothpaste, shampoo, all kinds of food products, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and agricultural applications such as organic plant fertilizer and animal feed. With more research, kelp may also be used to create biofuel and bioplastics. So, while there are tons of current applications for kelp, there’s also a lot of interest in developing new applications as well.

By selectively breeding kelp, we can improve traits that make it better for farming like increasing yield, improving thermal tolerance, and changing nutrient accumulation. In the wild, kelp provide habitat, reduce coastal erosion, absorb excess nutrients from the water, and add oxygen back to the ocean. Wild kelp are particularly sensitive to warming waters caused by climate change, which reduce their growth and can even kill them. Farmed kelp are also susceptible to increasing temperatures, which is where selective breeding can help.

- Scott Lindell shows off kelp individual undergoing warm water testing to assess thermal tolerance. Image courtesy of Dr. Amalia Almada.

On land, it’s easy to keep farms separate from their environments, but in aquaculture, where we grow things in the ocean, this is much harder. The newest development in research would help keep farmed kelp separate from their marine environment and serve as an ocean protection tool that limits any risks that farming efforts may pose to local ecosystems.

This technique for breeding sporeless, improved kelp comes from our knowledge and analysis of the kelp genome, which contains all its genetic information necessary for various biological processes like growing, responding to stress, and reproducing. In the wild, there are some kelp that are naturally nonreproductive. All kinds of living things experience infertility, and, in humans, it’s estimated that one in six people may be unable to reproduce. When the research team found these nonreproductive kelp, they analyzed their DNA and compared them against many kelp individuals until they found a difference in a particular region of the genome that they believe influences kelp fertility.

- Gary Molano of the USC Nuzhdin Lab shows me what kelp spores look like. Image courtesy of Arian Tomar.

By pairing two kelp together with similar, naturally occurring mutations that make them susceptible to infertility, the research team was able to produce a nonreproductive offspring that still inherited the improved traits of its parents, with the added benefit of being sterile. Due to the open nature of the ocean compared to land used for farming, sterility is a common trait in individuals grown in aquaculture. This new research would add kelp to that list of nonreproductive aquaculture products.

While I may be a science lover, I diverged from my educational interest in science a long time ago and have been focused on making films for my entire college experience. Needless to say, learning about kelp farming, selective breeding, and genomic analysis was a challenge! On top of understanding the science, I had to communicate through film what I knew to an audience that potentially knew nothing about kelp biology or even what a genome is. Luckily for me, a pretty image now and then helps keep a viewer’s attention. Oh hey, look below, a pretty image.

Now that you know where I’ve been, let’s return to the main plot: I’m at the beach and the fog is so thick, I can’t see a thing. I think back on the countless hours I spent poring over research papers, sitting in on lab meetings, and watching every video on kelp available on the internet. Now it’s finally my time to shine; it’s time to make the film. Aaaand I can’t see a thing.

The day before, I watched a video of surfers at Leo Carillo surfing around a kelp forest, and in the video, you can clearly see the kelp under the water. I came all the way out here so I could get similar footage for my video, and the fog has ruined any chance I have of seeing into the water.

I look at the ground, kick some sand around, and wonder if I just wasted a night of sleep on an unsuccessful trip to find kelp. And that’s when I see it. A small blade of kelp washed up on the beach.

All is not lost. I spend the next hours carefully positioning washed-up kelp, recording a few seconds of video, and repeating the process until I’m satisfied. Though I’ve found a silver lining in the clouds hovering over the water and found a way through the fog, my mission is not over. I’ll have to make the hour-long trek back out here so I can film kelp in the water. I pack up my camera equipment, making sure to keep sand out of gear and take one last look at the fog-covered beach. In the words of one of California’s coolest governors: I’ll be back.

I return the next day. It’s two in the afternoon. The sun is out, the sand is warm, and the beach is dotted with families enjoying the weekend. I scan across the ocean, spotting dark clumps of green swaying the water: success.

This project was one of the most rewarding I’ve had the privilege of working on during my time at USC. To communicate such a novel science story that can advance aquaculture and make kelp farming more sustainable, environmentally resilient, and economically viable was awesome. And the filmmaking wasn’t half bad either.

As I conclude my time with USC Sea Grant, I feel more empowered as a documentary filmmaker seeking to advance conservation and motivate informed action that makes our shared future more sustainable. Thank you to everyone who contributed to my learning and made this video possible. Go watch it now and leave a comment if you learned something new about kelp!