The Marine Exchange of Southern California, located in San Pedro, CA near the twin ports. Source: CAPT J. Kipling Louttit

12. Coordinating Vessels in the Ports of San Pedro Bay: The Marine Exchange of Southern California

Author: Dr. James A. Fawcett, USC Sea Grant Maritime Policy Specialist/Extension Director (retired)

Media Contact: Leah Shore / lshore@usc.edu / (213)-740-1960

Just as an airport needs air traffic controllers to weave arrivals and departures, so does a major seaport. In smaller seaports, the port itself is often capable of coordinating traffic into and out of its waters. However, in large seaports,, it is important to provide informational order to port operations. Since 1923, the Marine Exchange of Southern California (MXSOCAL) has been that manager for our twin ports, first to the Port of Los Angeles and then later expanding to include the Port of Long Beach. It is little known outside the ports and its purpose may seem mysterious or obscure at first until we realize why it is such a critical seaport function.

Port Coordinator

In the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach (POLA/POLB), the busiest of U.S. seaports, over 4,500 ships arrive each year, and they are crewed from a variety of nations. Some vessels make repeated visits to our ports, others come infrequently, but each requires assistance from a trusted agent who knows port operations and can assist the vessel while in port. The shipping agent or cargo agent is engaged by the carrier (the vessel operator) in advance of arrival. This arrangement is usually made by the carrier’s office, not by the captain of the ship, whose responsibility while at sea is providing safe navigation.

The agent needs to know when the vessel will arrive to ensure that berthing arrangements are made, tug boats are engaged, line handlers are on the docks to secure the vessel, and that port pilot services are ready to assume the responsibility for safe entry, exit, and docking of the ship. The challenge is that agents only know the arrival, departure, and shift information for their own ships; they schedule blind to other agents and firms. This is where MXSOCAL makes itself invaluable. Every day of the year, the MXSOCAL’s Maritime Information Specialists (MISs) contact all agents for all ships arriving, departing, and shifting around the ports, and collate the individual schedules into one consolidated schedule. The first and most essential role of the Marine Exchange is to be the coordinator and single point of contact for information for all vessels.

A busy seaport will experience many simultaneous activities—adjacent vessels seeking to depart, scheduling tug services and harbor pilot services for both arriving and departing ships, planning for hazardous cargo loading, and refueling activities—each increasing the potential for confusion or conflict in the port. For that reason, the Marine Exchange makes coordination possible by serving as a central clearinghouse for information about all these activities. Without it, confusion would be inevitable and, in fact, the overall management of the port and its many moving, constituent parts would be very difficult. Its day-to-day operation may seem ordinary and routine, but considering the wide variety of activities that take place in a busy seaport, without it, chaos would be a daily experience.

Vessel Traffic Service

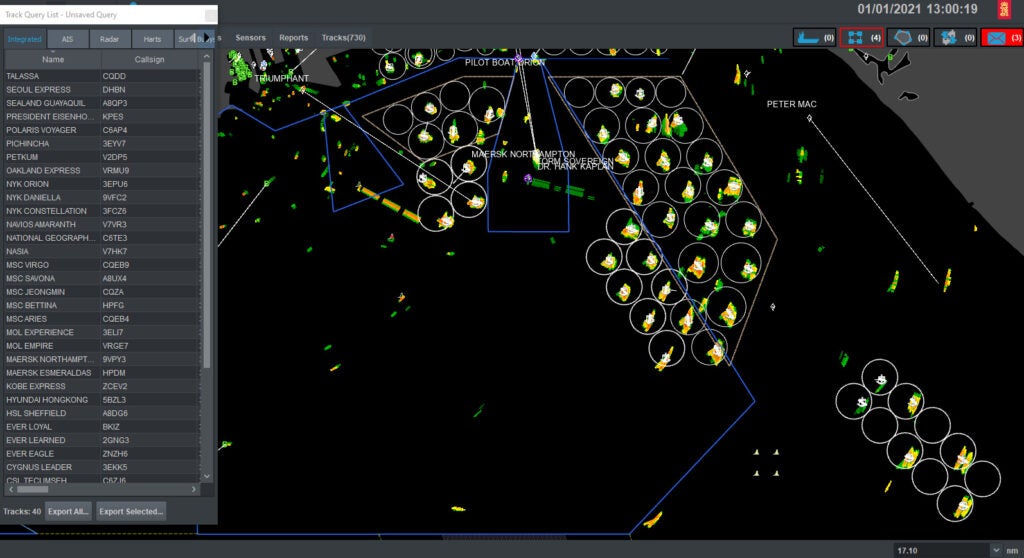

The second critical function of MXSOCAL is to operate the Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) for the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. If the MXSOCAL is the administrative scheduling and reporting coordinator for shipping movements, its partner, the VTS, is most equivalent to the responsibilities of an air traffic control system. Every major seaport has a VTS to coordinate the actual movement of vessels approaching, departing, shifting around, or at anchor in the vicinity of the port. The VTS in the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach is unique in the U.S. because it is a non-profit public/private partnership between the U.S. Coast Guard, and the MXSOCAL. The VTS is staffed by a mix of 11 MXSOCAL employees (many of whom have significant experience at sea in the Coast Guard, U.S. Navy, or as civilian mariners), and six active-duty Coast Guard Operations Specialists. Using sophisticated digital radar, computer, and radio equipment, they track all vessels[1] between Morro Bay and the Mexican border. The MXSOCAL and its VTS are led by CAPT J. Kipling Louttit, U.S. Coast Guard (ret.) whose predecessors were also experienced sailors, CAPT Richard McKenna, U.S. Navy (ret.), and civilian Master Mariner CAPT Manny Aschemeyer.

Funding

The MXSOCAL is a self-supporting 501c(6) firm whose funding primarily comes from two sources. The Maritime Information Service is funded by the charging customers who purchase the consolidated vessel schedules and other reports. The Vessel Traffic Service is funded by each arriving vessel paying a tariff based on the ship’s length and weight.

Tracking Vessels Through an Automated Identification System

In 2002, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the United Nations (UN) agency regulating international shipping, instituted a regulation that all vessels over 300 gross tonnes[2] must have onboard and operating a Class A-type Automated Identification System (AIS) transceiver. This piece of equipment is capable of transmitting a vessel’s unique IMO identification number, its position, course, speed, and other information to other vessels, which is received by their AIS equipment, shipboard electronic charting and data information systems (ECDIS), and to VTS facilities worldwide.[3]

Armed with this information, vessels in the vicinity of the two ports, as well as ship operations along the ~200-mile coastline of Southern California and the MXSOCAL, communicate with a wide swath of vessels in Southern California waters on a 24/365 basis. Their Maritime Information Specialists produce the schedule four days in advance of a vessel’s arrival at the ports to inform all interested parties of expected vessel arrivals. About a day in advance of a vessel’s arrival, the VTS begins tracking it. At 25 miles from the ports, about two hours before arrival, vessels check-in with the VTS and validate arrival information. They also validate that the vessel is cleared to enter port by the Coast Guard, whether the vessel is going directly to pick up a harbor pilot and go to a berth inside the harbor, or if it is heading to an anchorage outside the breakwater to wait in the queue for a berth. The VTS can also provide a host of other functions and information such as advising of a potential collision, advising a ship that its anchor may not be secure on the bottom (which may lead to the ship drifting out of its assigned anchorage), or the approach of severe weather.

Voluntary Vessel Speed Reduction Program

The Marine Exchange performs several other unique functions for the ports that benefit the local community. The first is tracking vessel speeds as they approach the ports under the Voluntary Vessel Speed Reduction Program. As was discussed in Blog #7, the two seaports have agreed on a Clean Air Action Plan because the Los Angeles air basin often is unable to meet federal clean air standards. Under this plan, ships are urged and incentivized to slow to 12 knots when they are 40 nautical miles from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, reducing their engine emissions and contributing to cleaner air. By slowing, the two ports have agreed to reduce their wharfage charges by 15-25%. Using information from the VTS, each of the ports is able to assess those ships qualifying for the fee reduction.

Providing Harbor Safety

Another important facet of the MXSOCAL is its role as a watchdog over marine operations in the two ports as the secretariat of the Harbor Safety Committee (HSC), established and supported by the California Office of Oil Spill Prevention and Response (OSPR). Its 24-member board was originally commissioned to ensure that harbor activities are safe from oil spills, however, the HSC also documents hazardous activities such as collisions, allisions[4], aids to navigation, anchorages, “near misses,” channel depth and construction, bridges, small craft, pilotage, tug escort/assist for tank vessels, under keel clearance, environmental impacts, and inclement weather, and standards of care for vessel movements. The HSC is responsible for a harbor safety plan and holds regular meetings with representatives from maritime industries, the ports, the U.S. Coast Guard, the U.S. Navy, public agencies, and interested members of the public.

A Public Record of Data Collection

The MXSOCAL may bring to mind the image of an old sailor sitting by the bay, smoking a pipe and perhaps mending a fishing net while watching ships sail by—they both have long and vivid memories of the history of port operations. However, unlike the old sailor, the MXSOCAL and its VTS are very busy on a daily basis, shepherding vessels, documenting harbor operations, and making a recorded memory in charts and reports of ship arrivals and departures. What is even better, is that this “memory” is accessible to public agencies, academic researchers, lawyers, historians, and the public who are seeking reliable, contemporaneous records of port operations. It holds data that can be useful in settling disputes between parties, information on the changing physical character of the two ports, the types of cargo handled, and the duration of vessels in port. It also holds the records of port disasters such as the S.S. Sansinena, a Liberian oil tankship that exploded in the Port of Los Angeles on December 17, 1976. Clearly, its repository of historical information is another valuable asset secured by a century of watching, listening, and coordinating on this busy coastline.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to CAPT Louttit for his contributions to and accuracy of the description of these critical seaport functions.

References

[1] All vessels which are of 300 gross tonnes and as such are transmitting their identity via the Automatic Identification System (AIS).

[2] Tonne is a metric ton or 2204.6 lbs. A vessel of 300 tonnes would weigh 330.7 short (Imperial) tons.

[3] US Coast Guard. (N.d.). US Coast Guard AIS Regulations, Now and Proposed. https://www.navcen.uscg.gov/pdf/AIS/USCG_AIS_Regs_Current-Proposed_v2.pdf

[4] An allision is defined as: “The running of one ship upon another ship that is stationary.” https://naylorlaw.com/blog/allision/