For the Love of the Beach

They say that happiness is a day at the beach. Aside from the physical comforts of warm sand and cool water, there is something exhilarating about being on the edge of a blue wilderness that is unpredictable and repetitive all at once. You never know what the tide will bring in, what that wave will feel like as you surf that day, or who you may meet along the shore. Yet, the familiar sound of seagulls and taste of sea salt can make it feel like you have returned home.

Despite this enduring beauty, our beloved beaches in Southern California and the animals that need them face many challenges including coastal water pollution, sea level rise, erosion, and even artificial light. In honor of National Beach Day (August 30th) and World Beach Day (September 1st), we would like to give you a glimpse at some of the beach-focused research which USC Sea Grant is currently funding in order to make sure our beaches and their ecosystems are healthy and resilient.

Challenge: Pollution

A critical component to a good beach visit is clean water. USC Sea Grant has a long history of funding applied research on beach water quality; especially along populated coastlines like Southern California, people who swim or surf in the water have a risk of getting sick from fecal indicator bacteria (FIB) such as E. coli. Usually levels of bacteria are below risky levels, but events like rain, increase in stormwater run-off, waste-treatment plant overflows, or change in currents can increase bacteria levels. Many water quality monitoring agencies in California have a two-day laboratory turnaround of beach water samples, and this time lag often results in the exposure of many beachgoers to contaminated water.

For more timely results, some water quality managers have moved to use data-driven models to predict the presence of poor water quality. However, these models to date have required extensive multi-year data sets to accurately predict water quality. This requirement automatically leaves out “data-poor” beaches where monitoring is infrequent or non-existent. USC Sea Grant is funding Professor Alexandria Boehm at Stanford University, who has successfully developed predictive models of water quality based on only two days of sampling. This means that even a data-poor beach could have accurate beach water quality data relatively quickly. Boehm’s team is making their model public, allowing resource managers, wastewater treatment plants, environmental groups, and even community-based science groups to build a predictive model for their beaches in a short period of time.

Concern is also growing over antibiotic-resistant bacteria. According to the Center for Disease Control, each year in the U.S. about two million people get an antibiotic-resistant infection. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria are jeopardizing contemporary medicine’s capacity to treat infections and diseases. Scientists are now focused on determining how antibiotic-resistant bacteria and genes get into and are transported through the environment and their effects on the human microbiome. One suspected source of human exposure to antibiotic-resistant bacteria is stormwater run-off in coastal waters, potentially putting surfers and other regular beach-goers at high risk. USC Sea Grant is funding a study by Professor Jennifer Jay at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) to illuminate the role of the marine environment in the transmission of antibiotic-resistant pathogens, specifically methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), to humans. Results so far show that swimmers and surfers are at the highest risk of MRSA infection after rainy events, especially the first rains of the season in the fall. These results have the potential to inform local public policy and management of beach closures for public health.

Challenge: Sea Level Rise

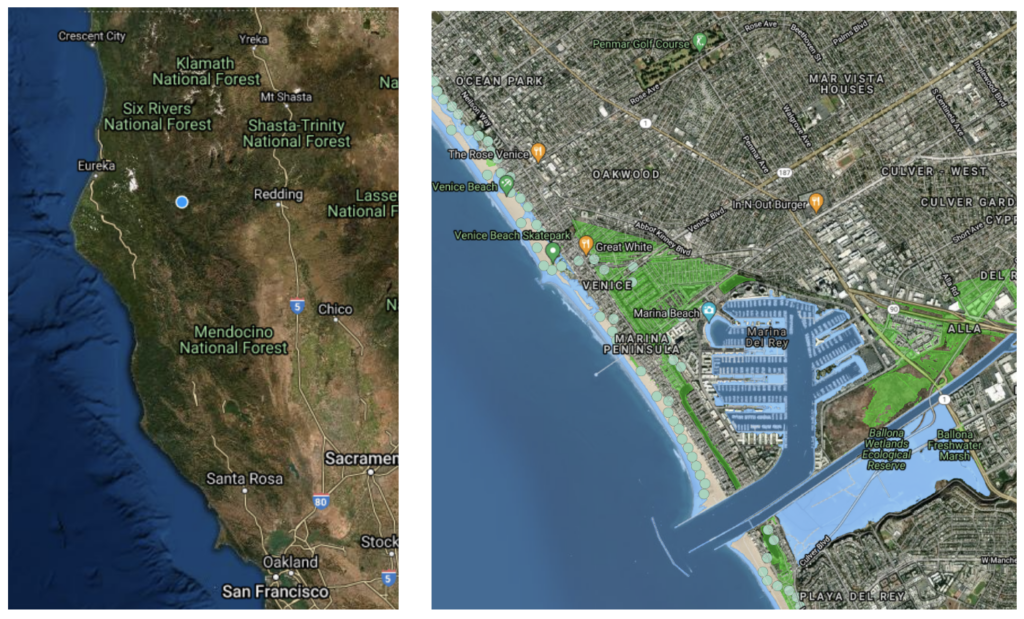

For coastal beach communities, one of the biggest threats of climate change is sea level rise, which can cause coastal flooding, threaten the stability of coastal infrastructure, and exacerbate the erosion of beaches and bluffs. USC Sea Grant has worked with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and their Coastal Storm Modeling System (CoSMoS) for years to facilitate across Southern California the model’s ability to predict coastal flooding and erosion driven by climate change. Recently, USC Sea Grant-funded the extension of the CoSMoS modeling into Northern California, with the goal to have a complete picture of the most vulnerable coastal areas in the state. One of the factors included in the modeling is beach erosion. The results of this study will be made public in an online tool to provide coastal communities the information resources to plan and adapt accordingly for their most vulnerable beaches and coastal infrastructure.

USC Sea Grant has also funded more locally focused in-depth analyses of the threat of sea level rise to beaches. Professor Ian Walker of Arizona State University is studying a 30-mile shoreline in Northern California which is the longest barrier system in California and includes some of the best remaining native, naturally functioning sand dune systems on the west coast of the United States. The barriers protect not only three local estuaries, but also neighboring communities and critical infrastructure. The resilience of the barrier system is at risk from ongoing impacts of accelerated sea level rise, as well as other threats such as changes in sediment supply from rivers and dredging, and invasive European beachgrass. Using sea level rise simulation models, Walker and his team have identified which sand dunes are most at risk. In coordination with local community-based nonprofits and organizations, education and restoration efforts are underway.

Challenge: Erosion

Cobbles, or small stones, naturally stabilize many California beaches. They have been used to construct artificial protective berms and influence shoreline change in the face of sea level rise. However, scientists still do not fully understand the physical and historical distributions of cobble or the dynamics of their motion. USC Sea Grant is funding Scripps Institution of Oceanography researcher Adam Young, in partnership with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and California State Parks, to generate the first quantitative study of cobble motions in California. The results will illuminate how cobble transport and dynamics influence and provide beach stability, and are likely to have important implications for coastal response to future sea level change.

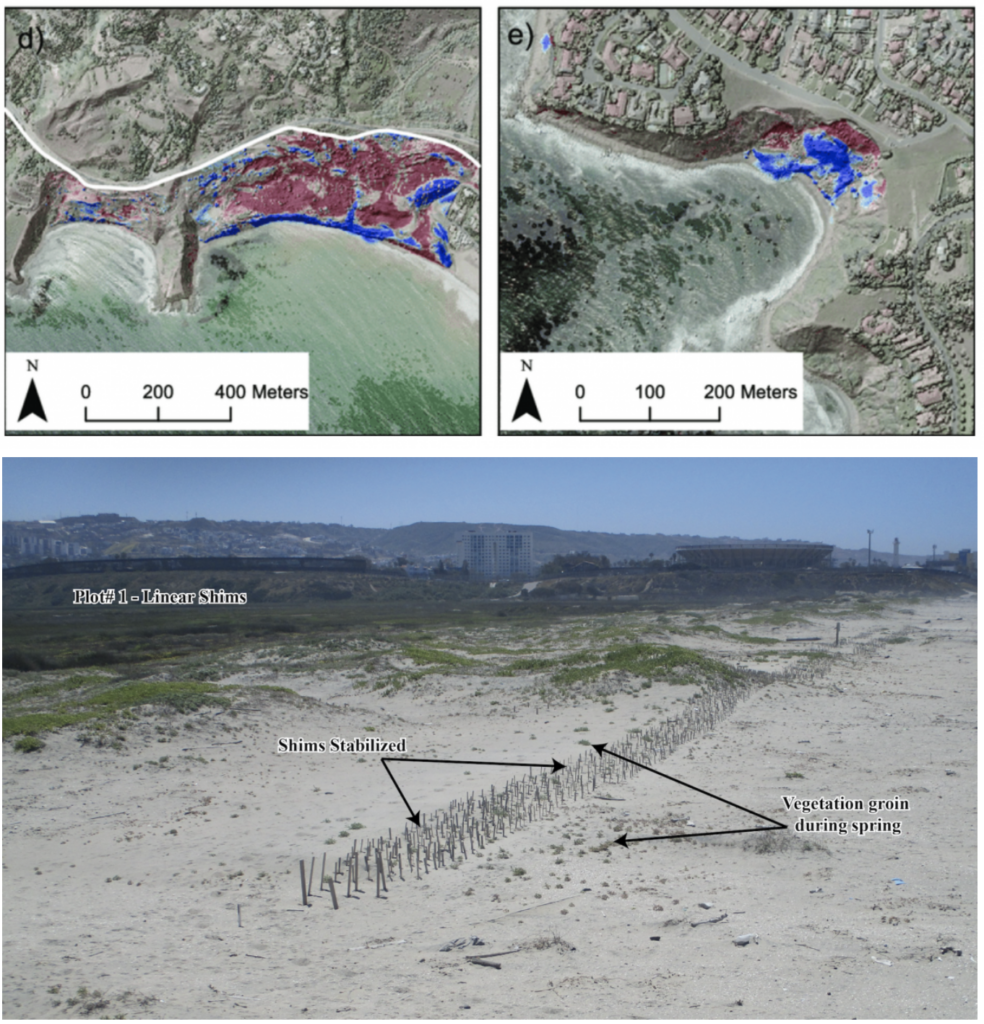

Like beach cobbles, coastal sand dunes are an integral part of natural coastal systems and historically occurred along much of the southern California coast. They provide coastal resilience by protecting inland areas against storm waves, sea level rise, flooding, and beach erosion. USC Sea Grant is funding a study by Coastal Environmentals, Inc., in partnership with the Tijuana River National Estuarine Research Reserve, to restore a coastal dune system within Border Field State Park in San Diego. Using a living shoreline approach, the project is rebuilding dune topography and restoring native vegetation to assess restoration techniques on a large scale, increasing wetland system resilience to sea level rise, and providing a model for habitat enhancement. Results to date show positive trends in sand accumulation in the experimental area where native vegetation is regrowing.

Challenge: Light

In addition to rich coastal biodiversity, Southern California has some of the brightest night skies on the planet. Unfortunately, artificial light at night disrupts a wide range of natural processes for beach animals, including foraging for food, migration, and nesting. USC Sea Grant funded a study led by Dr. Travis Longcore at UCLA to measure the quantity and distribution of nighttime coastal light pollution across Southern California. Using unique technology that only measures artificial light from the ground (as an animal would experience it), the study has published the largest dataset of light pollution measurements in the world. Longcore and his team have analyzed how artificial nighttime light impacts sensitive species like California grunion (fish that lay eggs on beaches at night) and Western snowy plover (a bird that nests in sandy dune areas). The plover prefers the darkest beaches while the grunion will use slightly brighter beaches, revealing that future management of sensitive beach species should include consideration of artificial light.

USC Sea Grant believes that it is possible to have healthy, sustainable beaches and beach ecosystems in an urban environment, and is committed to funding beach research like the studies above which lend themselves easily to immediate application, policy change, and action.

For more information about USC Sea Grant’s current research, click here.