The Power of the Model Minority Myth and the Need for Solidarity

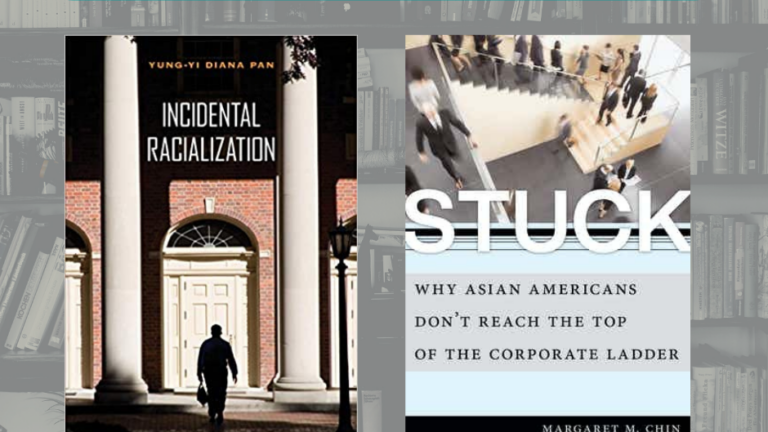

One time in high school, Diana told a friend’s parent that she didn’t like math. The parent looked confused, and asked: but aren’t you supposed to like math? This assumption followed her through college and into adulthood. The model minority myth is powerful by invoking an indifferent positive advantage called “Stereotype Promise.” This apparent optimism obscures controlling images and prejudice toward Asian Americans, according to our recent and emerging research. Margaret spoke to over 100 American-raised or -born finance, media and law professionals who graduated college between the 1980s and 2000s for her book, STUCK, and Diana is currently speaking with attorneys, physicians, and professors on the east and west coasts. Both of us find that Asian Americans experience racism differently from their Black or Latinx counterparts.

The model minority myth suggests that Asian Americans experience little adversity or that they lack solidarity with the concerns of other marginalized groups. This is not the case, as seen from research on Asian Americans and affirmative action. Positive, or neutral images shield Asian Americans from particular systemic racism experienced by other nonwhite groups, such as police brutality. Even so, these images connote abnormality and a deviance from a societally-accepted white norm. In this way, Asian Americans — and their concerns — are systematically ignored and marginalized.

The “model minority” concept originated in the 1960s. Sociologist William Pettersen, in an article for The New York Times Magazine, touted Japanese Americans’ ability to overcome discrimination during and after World War II. The characterization “model minority” seemingly elevates the status of Asian Americans as nonwhite minorities, but instrumentally drives a wedge between communities of color by pitting the “good minorities” (Asian Americans) against “bad minorities” (Black/African Americans). What’s missing from this narrative, however, is that both communities are systematically deemed divergent or othered from the standard, white cultural norm. Further, this myth undermines a long history of cross-racial solidarity between Black and Asian American communities.

The model minority myth actually does three things: (1) obscures anti-Asian American racism, (2) renders invisible Asian Americans from broader society, and (3) implies that solutions labeled as anti-racist are inappropriate for Asian Americans.

As two Asian American academics, we have been told by non-Asians that we do not understand racism or have not truly experienced it because we are “almost White” or not “people of color.” Diana’s current research finds that Asian American attorneys, professors, and physicians will describe “uncomfortable experiences.” Yet, these respondents stop short of labeling such interactions as racist because our society’s characterization of race-based discrimination does not include the experiences of Asian Americans. In Margaret’s book STUCK, most of her finance, media, and attorney respondents say that racism against Asian Americans existed during their parents’ youth. They refer to their own experiences as implicit bias. But, the bamboo ceiling is an outcome of these biases.

In STUCK, Margaret finds that her corporate respondents follow what she coins the “Asian American playbook,” a verbal checklist enunciating the following: being good at school, becoming leaders in extracurricular activities, and working hard. When they don’t progress up the corporate ladder, Asian Americans then consider themselves failing as “model minorities.” Almost all of Margaret’s respondents shared this story, such that she recognized this as an institutional problem that should serve as the basis for solidarity with groups that have been broadly “othered.”

Similarly, the Asian American law student respondents represented in Diana’s book, Incidental Racialization, jokingly shared that they elected to attend law school because they were not good at math, and thus couldn’t go to medical school. Their race – or otherness as Asian Americans – is heightened through interactions with peers and professors in the institutionally and culturally white space of law school.

When asked about diversity efforts, our respondents all say similar things: they’re not sure they’re included. And literally, they are often not counted even when studies reveal that Asian Americans are just as likely experience problems getting promoted, much like their Black and Latinx Americans.

Likewise, when there are stories in the press about racism in the professions, it often remains a Black (sometimes Latinx) and White story, leaving Asian Americans out of this very real American experience.

Employers will acknowledge the Lunar New Year with a Chinese food spread. However, anti-racist solutions, such as executive training for minorities that helped some of Margaret’s more senior executives advance are rare for today’s young Asian American employees. When Asian Americans do confide in co-workers, their experiences are dismissed while asked: “what are you complaining about?” Without knowing this larger picture, Asian Americans can be confused as to who or what to blame for their experiences and with whom they could be working in solidarity to overcome racism.

This is what the model minority myth does — ostensibly congratulates us while simultaneously leaning on the image to discount and marginalize our very own existence.

About the authors:

Yung-Yi Diana Pan is Associate Professor of Sociology at City University of New York – Brooklyn College and The Graduate Center

Margaret M. Chin is Professor of Sociology at City University of New York – Hunter College and The Graduate Center

© 2021. This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.