TPS: Living in Between, Neither Here Nor There

On June 24, 2019, nearly 9,000 U.S. residents with Temporary Protected Status (TPS) from Nepal will be losing their TPS status. The Secretary of Homeland Security decided to terminate the status on the grounds that the initial conditions (environmental disaster) for which TPS was granted, are no longer met. Ironically, just this year on January 8, 2019, the U.S. Department of State issued a travel advisory for Nepal, warning individuals to practice extreme caution due to political violence. But what are the effects of this sudden termination for TPS recipients, their families, and the communities they have long been a part of? Particularly, when some of these countries like Nepal, El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Sudan might not be considered safe? This essay aims to provide important information on TPS, including its history, the status quo, the most recent estimates of recipients across the United States, and the social impact that TPS has for individuals and immigrant communities.

Currently, the 10 countries with TPS designations are El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. Under the Immigration Act of 1990, the Secretary of Homeland Security can designate a country for TPS due to ongoing armed conflict, an environmental disaster, or other extraordinary and temporary conditions that prevent nationals from safely returning to their home country. Individuals who are granted TPS are permitted to legally reside in the United States, obtain an Employment Authorization Document (EAD) to work legally, and can be granted a travel authorization (Advanced Parole). Far from permanent, TPS can only be granted for 6, 12, or 18 months at a time.

While numerous TPS designations have been targeted for termination recently, ending TPS is not new. In the past, TPS has been granted to 12 other countries for which it has since expired. Figure 1 below lists these countries, their designation date, and expiration date.

Figure 1. Countries with Previous TPS Designations

|

Country |

Designation Date |

Expiration Date |

| Angola |

2000 |

March 29, 2003 |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina |

1999 |

February 10, 2001 |

| Burundi |

1997 |

May 2, 2009 |

| Guinea |

2014 |

May 21, 2017 |

| Guinea-Bissau |

1999 |

September 10, 2000 |

| Kuwait |

1991 |

March 27, 1992 |

| Lebanon |

1991 |

April 9, 1993 |

| Montserrat |

1997 |

February 27, 2005 |

| Province of Kosovo |

1999 |

December 8, 2000 |

| Rwanda |

1994 |

December 6, 1997 |

| Sierra Leone |

2014 |

May 21, 2017 |

Note: Liberia is excluded from the chart because it has been granted TPS and DED interchangeably since 1991. See https://www.justice.gov/eoir/temporary-protected-status

Source: Office of the Federal Register, National Archives. Data accessed, February, 19 2019, available at https://www.federalregister.gov/

In 2016, TPS terminations were issued for Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone on the basis that the countries’ conditions for TPS designation were no longer met. Yet, the case of Liberia is unique in that qualified nationals were also granted Deferred Enforced Departure (DED). Under DED, recipients are protected from deportation, can obtain an EAD to work legally, and can be granted a travel authorization (Advanced Parole). Under the president’s discretion DED is issued but DHS establishes the requirements. While TPS for Liberia was issued in 1991, DED was later issued in 2000. Since then, TPS and DED designations for Liberia have been extended interchangeably. To summarize these complex extensions, TPS for Liberia expired on May 21, 2017 and DED for Liberia is set to expire on March 31, 2019.

More recently in 2017, the Secretary of Homeland Security announced the termination of TPS for El Salvador, Honduras, Haiti, Nicaragua, Nepal, and Sudan. However, in 2018, the terminations for El Salvador, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Sudan were countered under Crista Ramos, et al., v. Kirstjen Nielsen, et al.,resulting in the protection and extension of TPS until further resolution. Because the terminations for Honduras and Nepal were announced after the case was filed, these recipients filed a separate class action lawsuit in February of this year.

In the case of Somalia, South Sudan, Syria, and Yemen, TPS designations were extended. Figure 2 summarizes the countries currently under TPS designation, their designation date, whether they are protected by the preliminary injunction, their current TPS termination status, and their expiration date.

Figure 2. Summary of the Current Status of Countries with TPS Designations

| Country |

Designation Date |

Protected by the Preliminary Injunction |

Terminated |

Expiration Date |

| El Salvador |

2001 |

X |

|

September 9, 2019 |

| Haiti |

2010 |

X |

|

July 22, 2019 |

| Honduras |

1999 |

|

X |

January 5, 2020 |

| Nepal |

2015 |

|

X |

June 24, 2019 |

| Nicaragua |

1999 |

X |

|

April 2, 2019 |

| Somalia |

1991 |

|

|

March 17, 2020 |

| South Sudan |

2011 |

|

|

May 2, 2019 |

| Sudan |

1997 |

X |

|

April 2, 2019 |

| Syria |

2012 |

|

|

September 30, 2019 |

| Yemen |

2015 |

|

|

March 30, 2020 |

Source: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2018. Data accessed, January 8, 2019, available at https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/temporary-protected-status

Considering current TPS recipients living in the U.S., about 61 percent are from El Salvador, 18 percent from Honduras, and 15 percent from Haiti. These three countries comprise the vast majority of TPS recipients. Figure 3 below highlights the percentage of TPS recipients by country of origin.

Figure 3. Percentage of TPS Recipients by Country of Origin, February 2019

*Other category includes TPS recipients from Liberia, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen.

Note: Liberia is currently under Deferred Enforced Departure (DED).

Source: These numbers are calculated using the 2016 5-year American Community Survey (ACS) microdata from IPUMS.

TPS recipients are, for these big three countries of origin, a relatively large share of those immigrants who lack status as lawful permanent residents (or do not hold a student or other visa). For example, around 42 percent of Haitians in this legal status limbo have TPS as well as about 31 percent of Salvadorans and 16 percent of Hondurans. And while it might be easy to think of the uncertainty around TPS as affecting only individuals with TPS, the requirements necessitate many beneficiaries to be long-settled and thus highly likely to be integrated into families and communities.

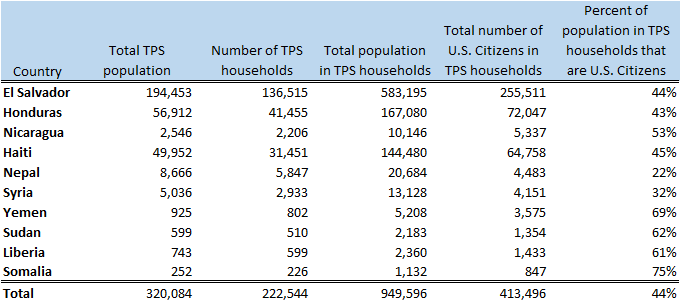

To illustrate this, Figure 4 breaks down the total TPS population, the number of TPS households, the total population living in TPS households, and the total number of U.S. Citizens in TPS households. As seen below, it is estimated that there are over 220,000 TPS households and approximately 44% of the population in these households are U.S. Citizens. The truly startling number: nearly one million people have TPS themselves or live in a household with a family member who is a beneficiary of TPS. Terminating TPS would disrupt families, potentially forcing family members to separate or relocate to a country foreign to them. Already, families are living with the fear of separation that creates stressful situations, compromising the well-being of adults and even children.

Figure 4. TPS Population and Households, February 2019

Note: Liberia is currently under Deferred Enforced Departure (DED).

Source: These numbers are calculated using the 2016 5-year American Community Survey (ACS) microdata from IPUMS.

Indeed, while TPS and DED recipients are currently protected, the temporariness of this status referred to as “liminal legality”, (a tenuous legal, social, and psychological position), has become an indefinite cycle of instability with its own limitations. TPS allows individuals to obtain better paying jobs, access driver’s licenses, and participate in society’s institutions and civic organizations. However, this “liminal legality” creates a sense of blocked mobility when accessing resources or employment opportunities. For instance, not all employers recognize EAD as a legal work authorization. Moreover, the lack of consistency with the renewal process, including the anticipation of re-approval and reregistration that varies by country, fuels a permanent fear of deportation.

Although TPS and DED may have once been a suitable solution, these statuses have turned into indefinite cycles of uncertainty. Year after year, organizations like the African Communities Public Health Coalition, Adhikaar, Haiti Advocacy Working Group, CARECEN, and the National TPS Alliance have advocated for TPS extensions for most of these countries. However, some of these extensions eventually terminated. We can no longer ignore how such “liminal legality” has only been a Band-Aid approach to a problem that needs a comprehensive and institutionalized solution. As looming expiration dates for certain countries quickly approach, it is time to strategize and rethink a more permanent and sustainable policy solution for an impending scenario that would impact nearly one million people.

About the authors

Learn more about the blog post authors on the staff page.

Dalia Gonzalez, Thai Le, and Manuel Pastor.