Food, Class and Emigration Experiences: Finding Sources in the Special Collections

In this blog, 2023-2024 Breslauer, Rutman, and Anderson Research Fellow Julie Fitzpatrick discusses her exciting finds in the USC Library Special Collections during her month of research.

My research investigates German Jewish women’s relationship with food during the prewar, wartime and postwar periods, analyzing how they navigated prewar emigration, antisemitic decrees, hiding spaces, ghettoization, concentration camps, death marches, railway journeys, DP camps, and postwar emigration all through the prism of food. I knew the VHA testimonies would offer a treasure trove of sources for me to draw from. Almost every single oral testimony I consulted referenced food in some capacity. However, I would like to use my blog post to discuss one of the most rewarding and interesting parts of my month in residence, having access to the Special Collections at the USC Doheny Memorial Library.

One thing that drew me to research here were the private papers of the German Jewish émigrés Lion and Marta Feuchtwanger. Lion and Marta Feuchtwanger were bourgeois Munich-born Jews who were part of the literary and artistic circles of prewar Europe. They spent a lot of time in North Africa, Italy, and France, which is where they were when Vichy France sent a number of Jews to internment camps. They managed to escape the southern French internment camps and travel to Portugal, where they each boarded separate ships to New York. In 1941, the Feuchtwangers moved to Los Angeles, where a large number of European intellectuals and artists were taking up residence.

Their entire personal archive was bequeathed to the University of Southern California. I was intrigued to see if food was part of this vast archival collection, but I was not sure if I would find anything of note for my own research. Searching for key terms like ‘cookbooks’ and ‘recipes’ did not reap any results in Marta’s papers. Instead, I searched things like personal ephemera, personal manuscripts, and scrapbooks in the hopes that there could possibly be something useful there.

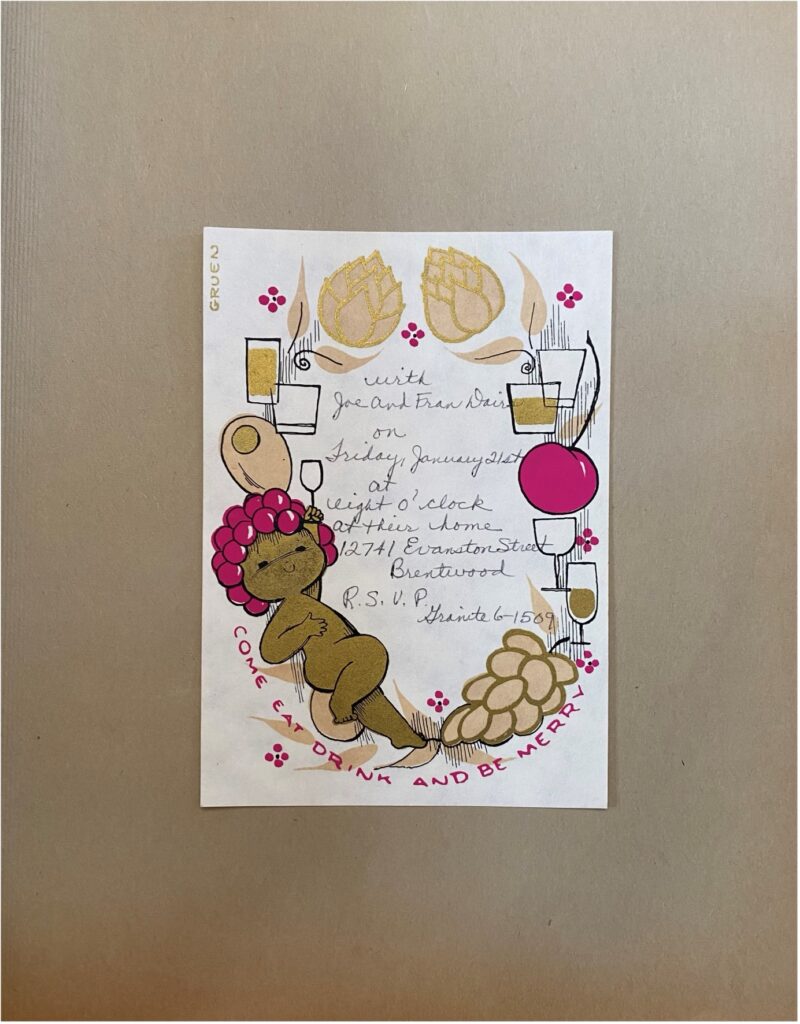

In one scrapbook, every leaf offered a snapshot into Marta’s life. There were many invitations to dinners, many of which were formal. One stood out. A jolly cherubic figure invites Marta to ‘come eat, drink and be merry’. The couple had planted deep and meaningful roots in Los Angeles and had many friendships to show for this. The friendly invitation bespeaks the socializing Marta continued to do, even after her husband’s death, and the ways that food and drink were part of her life in LA and the communities she made.

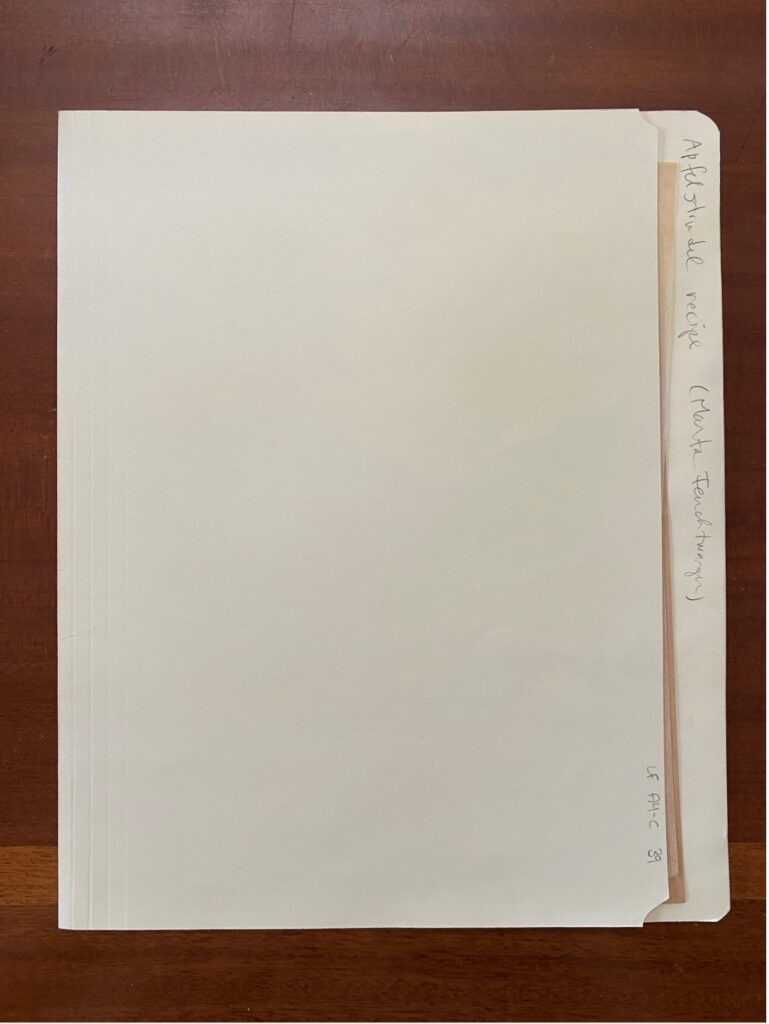

In Lion’s papers a search for recipe resulted in an apple strudel recipe of Marta’s, and it must have been particularly good as a folder is dedicated to it in one of his archival boxes.

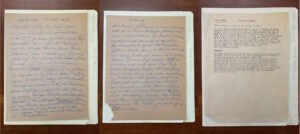

The filling calls for a fully homemade concoction. It begins, ‘you can use applesauce in cans, but it will be a little too runny and you’ll have to mix in cracker crumbs warmed in butter’. In the folder is the hand drafted version of the recipe, which appears to have been written on scrap pieces of paper from one of Lion’s manuscripts, this is followed by the typed out instructions for the strudel pastry and filling. It feels like a sentimental document in this box of papers and was evidently a much loved recipe that provided a connection with the German part of their identity.

In Marta’s papers, there are numerous transcripts and manuscripts about different aspects of their life as exiles. In an oral history transcript, we learn about their adventurous trips around North Africa and Italy in the 1910s and 1920s, where they lived in, and I quote, ‘relative poverty’ as bohemian travelers. On these adventures they sampled delicious fresh produce – tomatoes and fresh fish – in elegant places like Capri.

We also learn about the community of German-speaking exiles they were part of in Los Angeles. There are countless references to glamorous dinner parties where things like lobster and avocado were served, a combination enjoyed by the Feuchtwangers before it became popular. Marta is keen to emphasize this, suggesting they were culinary trendsetters. The Feuchtwangers would spend New Year with Charlie Chaplin, and Christmas at the Brechts, a couple they knew from Germany, where they’d eat goose and mirror carp. This Christmas tradition was something the Feuchtwangers transplanted from their lives in Germany into their new life in LA.

Lion’s personal papers support this picture of their rather glamorous life where food was part of the story. There are guest lists to teas and dinners hosted by the Feuchtwangers. Chaplin is a name on one these. There are also receipts from a two-month stint in New York in 1947 where they stayed at the Sherry Netherland Hotel on Fifth Avenue, a five star establishment for society’s elite. There are eight invoices from the Sherry Wine & Spirits Company – a few orders are for the rather expensive and luxury champagne houses of Bollinger and Veuve Clicquot.

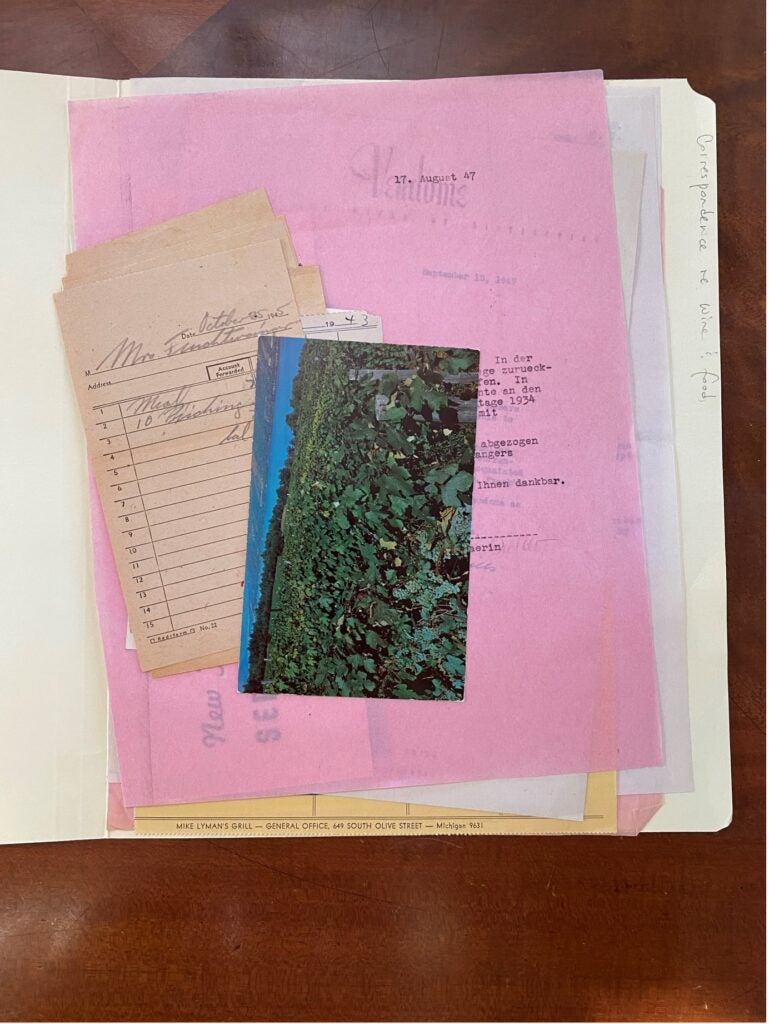

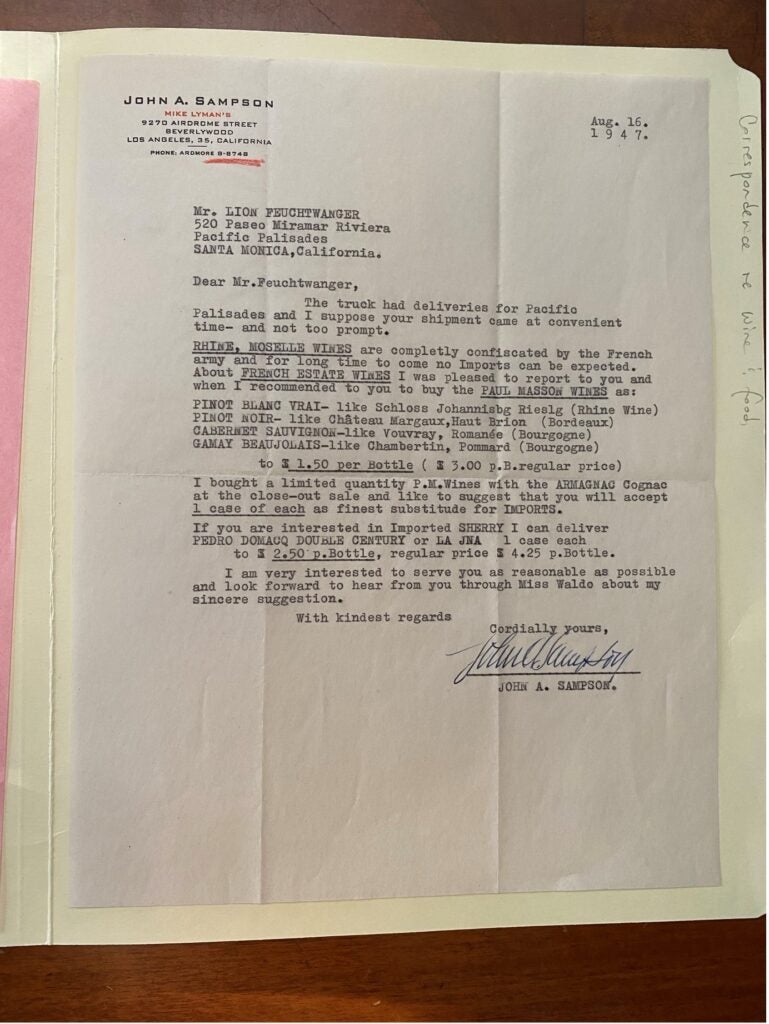

There is another folder dedicated to ‘correspondence re wine and food’, which includes receipts and invoices of Marta’s for food items like duck. It also includes letters of interest for things like ‘Scotch grouse’ – not the famous whisky, but the game bird – and German wine, which the Feuchtwangers are informed they cannot obtain because the French army has confiscated it and denied permission to export it. I am sure there is something to be said about diplomacy and wine heritage with the French army confiscating German wine, especially as the letter goes on to inform Lion that there is a whole host of French wines he can purchase. The archival collection is full of animated and entertaining descriptions of the Feuchtwangers’ lives from bourgeois German Jews to bohemian European travelers to famous Los Angeles residents with connections across the artistic spectrum and a food scene to match.

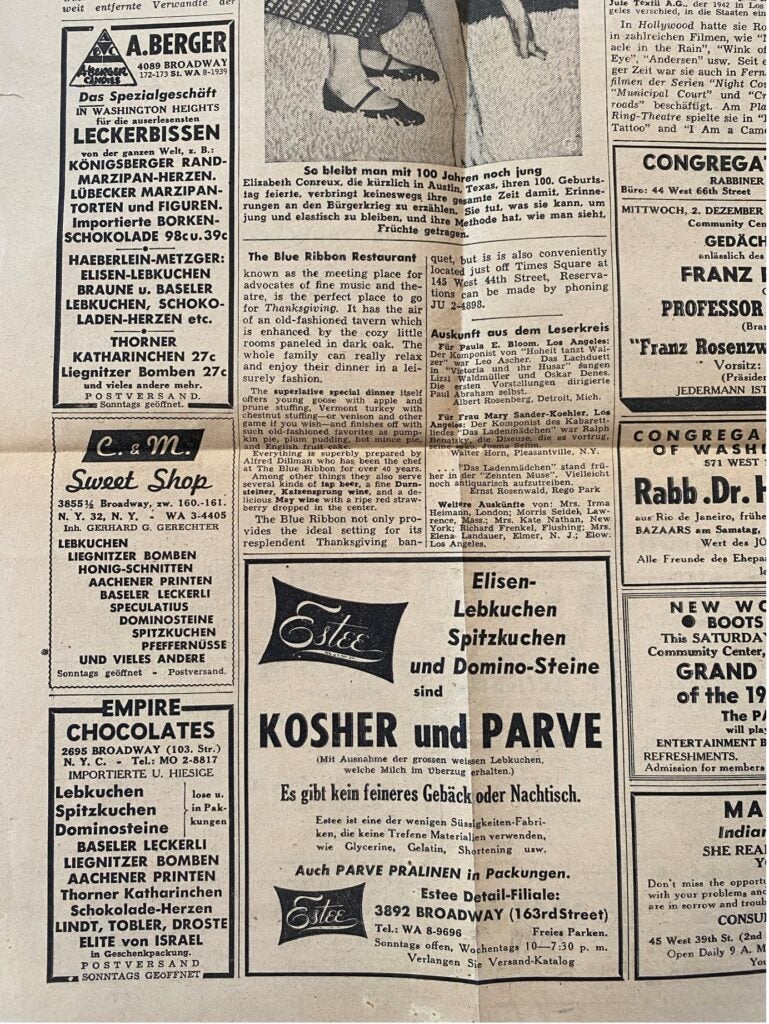

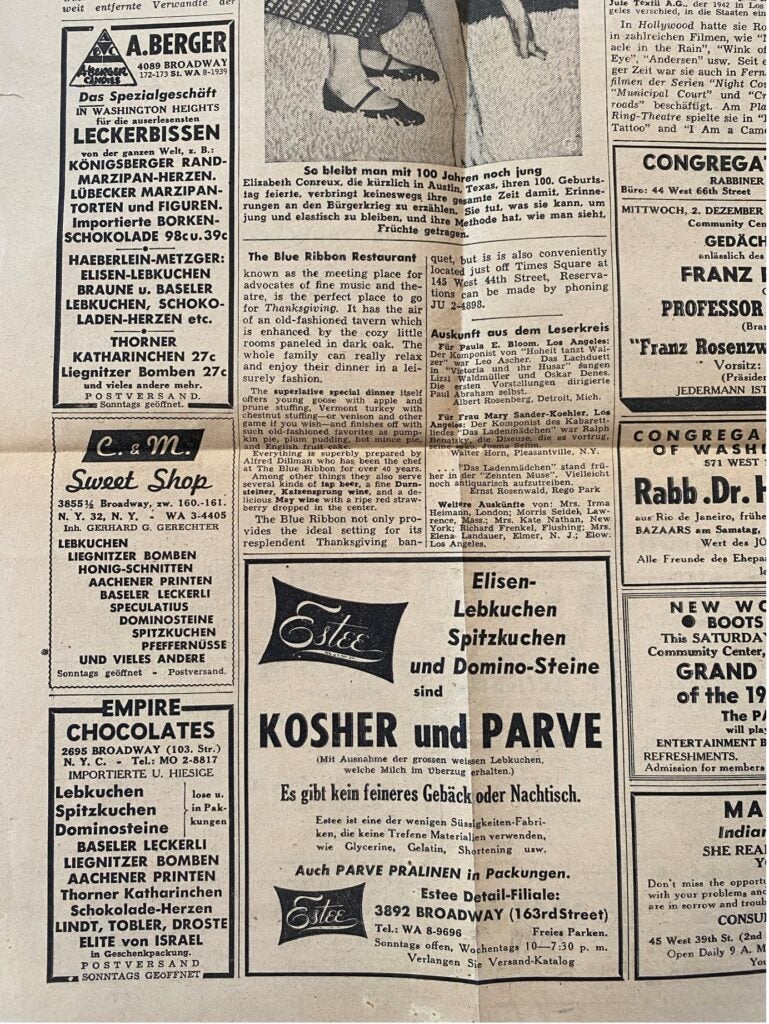

To conclude this blog post, I would like to focus on a newspaper clipping I found in Marta’s personal ephemera. It is an excerpt from a November 1959 edition of Aufbau. Aufbau was a periodical founded in 1934 in New York City as a newspaper for German Jewish immigrants. The clipping I found was from their Thanksgiving edition and across either side there are adverts and articles about food, including one that talks about the historic relationship on Thanksgiving tables between turkey and cranberry sauce. There are countless adverts for chocolate and sweet shops that sell kosher and parve treats.

When I found the page, I was not really sure what to make of it. There were no supplementary documents to explain its positioning in one of Marta’s scrapbooks, nor any evidence that Marta bought produce from the various delicatessens being advertised. I was intrigued by it and thought it spoke of Marta’s continued connection to her German Jewish identity – and food’s role in this – whilst simultaneously having fully embraced life in Los Angeles. However, the next day I was listening to various VHA testimonies of German Jewish émigrés and came across the testimony of German Jew Bianca Berger.

Bianca Berger emigrated to Cuba in 1939 with her young family and moved into a boarding house where they would rent out the rooms and she would cook for the residents. In Havana, the Berger family started a small clandestine business of selling candies. The Cuban authorities, with a little bribe, turned a blind eye to their entrepreneurial endeavours. This business was to become a more significant feature of the family’s life as German Jewish emigres when they finally secured visas to move to New York in 1941. Within three months of being in New York, the Bergers set up a ‘tiny little candy store’ on Broadway. Their first shop was next to a butchers, which Bianca hated because it made their sweet shop smell of meat. After about one and a half years they could afford to move into a bigger store across the street, which Bianca describes as ‘a real store’.

A lightbulb went off when I realised that the advert I had been most drawn to in the newspaper clipping was for A. Berger’s Broadway store. A. Berger is Alfred Berger, Bianca’s husband. The advert publicized the shop’s most exquisite delicacies, including gingerbread, fruit and marzipan cake hailing from Lower Silesia, honey slices, spiced cakes from Aachen, delicacies from Basel, and many other things.

I had been drawn to this advert the day before because I felt it demonstrated that German Jews who were carving a life for themselves in the United States utilized food as a means to not only make a living but also to connect the various parts of their identity in an emigratory environment. I had now also found a connection between my work in the Special Collections and my work with the VHA.

In her testimony, Bianca goes on to say how a lot of past acquaintances and friends from Germany found them again through these advertisements in Aufbau. Their store became hugely popular. She describes them making marzipan that filled the street with a sweet smell that caused huge queues and gatherings outside the door, especially at Christmas. The Berger’s candy store became a hub for German Jews. As Bianca said,

“It was a place where everyone met, where German Jews who couldn’t speak English yet and they had so many worries […] They came in, in the evening, to meet in our little store and talk everything over. It was like a family house.”

For displaced, even homesick Jews, familiar foods provided a comfort and connection to home. Urban pockets of Jews from earlier migrations had created a lively culinary scene of kosher butchers, delis, and continental stores that would sell foodstuffs recognizable to German Jews. This is where the Berger’s store, which sold traditional German kuchen from different regions, fit in.

The store was a quintessential German Jewish food store, transplanted into the bustle of New York City. It was so German that their late-teenage daughter, Inga, found a job in another candy store in the Bronx to learn, and I quote, “the American way of candy making.” Bianca describes how “we had a European way […] We were connected with our German people and our European people and she wanted to see how [it was done] the other way around.” Both Bianca and Inga were forging their way in their new lives as middle-class German Jewish women thrust from their home, via Cuba to New York City. Bianca stuck to her German Jewish identity, whilst Inga sought out the American culture she was going to grow up in.

In consulting the Aufbau archival records – which are digitized – I found the article, interested to contextualize the two pages in the wider publication. Marta’s clipping came from a 36-page edition where food or adverts for grocery stores are not mentioned again. Additionally, while there are numerous other newspaper articles in her personal collection, those articles were all about her and the interviews she had given to journalists. In the archival collections I consulted, this clipping of Aufbau’s 1959 Thanksgiving edition is the only one I could find that has absolutely nothing to do with Marta. Why did she choose to keep a page of adverts for predominantly New York based German Jewish food stores? Of course, we might never know why Marta kept this clipping but it is fascinating to hear another survivor talk about these adverts and their importance to her and her family’s life abroad. My month in residence was incredibly fruitful on all fronts, but this overlap between the VHA testimonies and Special Collections felt like a special and exciting find.

Watch Julie Fitzpatrick’s lecture about her research here and read a summary here. Read an interview with Julie Fitzpatrick here.