A New Methodology

By Tim Cole, Alberto Giordano, Anne Kelly Knowles, Paul B. Jaskot

In January 2014, four scholars from the “Holocaust Geographies Collaborative”—an international, interdisciplinary group of researchers—spent a week at USC to work intensively in the Institute’s Visual History Archive. Their charge was to evaluate the link between personal testimony, the index of the archive and geography.

The Holocaust Geographies Collaborative has its origins in a 2007 summer research workshop sponsored by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, where a team of nine researchers met to experiment with geographical concepts and methods that the researchers thought could lead to new understanding of the Holocaust as an event that occurred in both space and time. In the years that followed, we worked with testimonial evidence to varying degrees, most notably in a study of the evacuations—or “death marches”—out of Auschwitz in January 1945 and another of Wehrmacht atrocities in Belarus, but our projects have primarily focused on building digital infrastructure to establish the structural geographies of Holocaust locations and events. For the next phase of our collaborative research we have decided to systematically explore the potential of testimonies as a source for geographical analysis. Testimonies provide a profound source with which to reconstruct the social circumstances of the victims. For example, testimonies could help us study how social networks (e.g., families) move through space and time.

We are convinced that the Visual History Archive’s index of nearly 52,000 interviews will enable us to expand the next stages of our work by mapping thousands of survivor trajectories through the Holocaust. In the course of our exploration of the archive, it quickly became clear that while the index contains a great amount of geographical information—places of birth, residence, incarceration—there was far richer material within the testimonies themselves. For example, working with the testimony of Gilberto Salmoni, an Italian survivor, we came to see that while the index allowed us to map the Salmoni family’s movements through Italy and into the camp system, only listening carefully to his testimony revealed the fine grains of experience we now seek to understand. The index might provide a city’s name where an individual spent time during the war, but only the interview offers the micro-geographies of frequent movement within a city and will help us reconstruct the spatial trajectory of the victim through a series of Italian detention camps before final deportation to camps outside Italy. And only at that level could we glean the significance of both movement and places to Holocaust survivors. In his testimony, Salmoni describes places, people, and events that unfold at a continental scale.

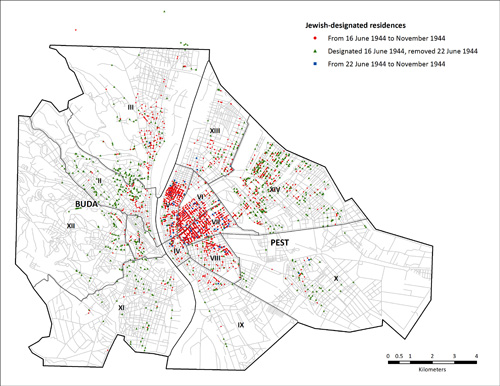

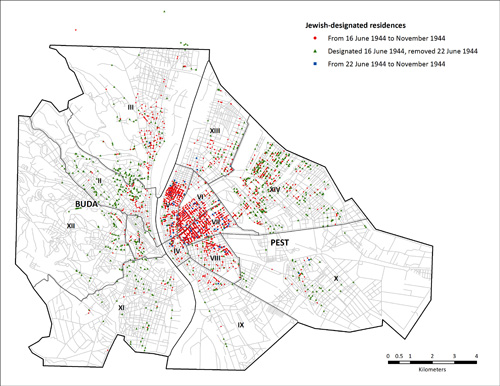

Judith Agular’s story, on the other hand, takes place entirely in Budapest, as she crisscrossed the river Danube from Pest to Buda, then back to Pest, and over to Buda again. But when Judith’s story is mapped conceptually, it is clear that she moved through a series of distinct places, each with particular meaning. Forced to leave her family home when ghettoization was implemented in June 1944, Judith moved with her father, mother, and aunt into one room of a crowded two-room apartment. From here she—along with thousands of other women and men of working age—during an armed raid by Nyilas (the Hungarian fascist party) in the fall of 1944 was taken to a brick factory in Obuda, Here Judith huddled with five women from the ghetto apartment building to keep warm. Although most of these prisoners were marched westward, Judith was released and returned to her home district, where she lived and worked in a Red Cross children’s home in the so-called “International Ghetto” area. She escaped another Nyilas armed raid by fleeing to a nearby convent. She finally found a hiding place in a Buda timber yard owned by a Communist sympathizer, the home of a non-Jewish acquaintance, and the apartment of her non-Jewish uncle. It was he who placed her with a caretaker of a four-story apartment building in Buda. Judith remembers the woman as being “cruel.” She was sheltered there until liberation in early 1945.

As Gilberto’s and Judith’s testimonies unfolded, it was clear that rather than comparing the spatial trajectories of thousands of survivors like Judith, studying the particularities of one individual’s movements would enable a deeper explanation of what kinds of places were seen to offer safety or opportunities for resistance, how these places were experienced by various survivors, and how interpersonal networks played a role in survival and resistance. A new methodology of Holocaust geography was right before our eyes, talking to us.

Listening to testimonies of other survivors who worked at many sites of forced labor, we further realized that remembered details of work places and relationships with fellow prisoners and perpetrators are vital for understanding how labor could both save and kill. Having mapped the general patterns of specific kinds of forced labor in the SS camps system, we now saw a vast new terrain of evidence to explore. The testimony reveals how prisoners experienced forced labor from place to place, and how the characteristics of those places and the people who inhabited them created fleeting moments of opportunity or luck or comradeship – chances to counter the extreme force of Nazi brutality. Furthermore, labor is described not so much in terms of specific spaces but in terms of spatial relationships of proximity and distance in space and in time. For us, this topological understanding of space suggests that survivors perceived the places of forced labor, and not as the physical locations that the SS so carefully planned but as places formed through experience.

Two overlapping ideas became increasingly important to us. Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, we became aware of the importance of place in survivors’ Holocaust experiences. Geographers tend to distinguish between “space” and “place,” seeing the former as a more abstract notion and the latter as imbued with meaning. Previously, much of our work has focused on space, for example, the growth and demise of the SS camp system across Europe, the building of Auschwitz, or the shifting shape of ghettoization in Budapest. Such work is critical for placing survivor testimonies within the broader geographies of ghettos and camps, but it says little about how those places were experienced, understood, reworked into sites of resistance or hiding, and later retold in postwar interviews. After watching multiple testimonies, we came to see them as central to any understanding of the Holocaust as an event experienced as a series of places lived and recollected by the victims as relationships, not only with the physical world of the ghetto, the camp, or the train but with other people. And that’s how place is often described: as geographies of relations, and quite particular relations at that. In fact, one of the aspects that struck us most while listening to testimonies was the survivors’ tendency to detail their relationships with other individuals or bystanders, even when these relationships incorporate feelings of fear and danger, while largely avoiding descriptions of perpetrators. Alongside this, a second theme emerged from our analysis: that the spatial is social and the social is spatial. As people, like Gilberto and Judith, moved through a series of places, social networks played a critical role in the meaning of those places and the role they played in survival. For Gilberto, a remark by an acquaintance at the Milan train station prevented the entire family from being immediately deported to Auschwitz. Factory workers and political prisoners in Milan offered Gilberto’s pregnant sister Dora extra food and protection, although her ultimate fate was to be murdered in Auschwitz with her mother and father. For Judith, her aunt joining them in the ghetto house was critically important because she had worked in a bakery before the war and so could get hold of bread. Judith’s journey to Buda at the end of the war was a journey not just to a place but also to a person—the non-Jewish uncle who ultimately found a hiding place for her.

Testimonies are not only a narrative of places, times, and events but, perhaps more profoundly, a narrative of social relations, which are continuously broken apart and re-created through space and time. Our week exploring the Visual History Archive and working together sharpened our interest in understanding how places and social relationships might help explain survival, and has provided a basis for developing a larger research project in connection with the USC Shoah Foundation Center for Advanced Genocide Studies. This project will be centered on a synergistic approach to narratives, in which we will study survival as the product of relationships between geography, history, and the victim’s social status and social networks, with the ultimate objective to develop an explanatory framework for survival for Holocaust and genocide researchers. We hope our research will also result in new and improved methods of indexing testimonies, which will allow teachers, students, and the general public to develop personal paths of exploration of the Visual History Archive and other similar archives.