L.A. consistently proves resilient in the face of disaster

Los Angeles is defined by diversity, opportunity, and perhaps more than anything, resilience. From fires to floods and from earthquakes to civil unrest, its infrastructure and spirit have been repeatedly tested.

Many of these trials have driven systemic change, including a transformation of the Los Angeles River, earthquake safety advances and police reforms.

“Resilience isn’t just a necessity here; it defines us,” said historian of California and the West, William Deverell, Divisional Dean for the Social Sciences at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. “This is in part due to our environmental vulnerabilities, the potential for disaster. In crises, neighbors help neighbors, leaders learn, and Los Angeles aims to rebuild stronger.”

The most destructive fires in U.S. history

The latest deadly calamities to test Angelenos’ mettle, the Pacific Palisades and Eaton wildfires claimed nearly 30 lives and caused unprecedented destruction, reducing entire neighborhoods to ash. The fires displaced thousands from their homes and caused an estimated $250 billion in damages — the costliest natural disaster in U.S. history.

“Despite the exceptional nature of what’s transpired and is transpiring, I fear we are getting a look at a new, terrible and tragic normal,” said Deverell, director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West. As climate change accelerates, experts warn, such disasters will only become more frequent and severe.

History, however, offers valuable lessons and a roadmap for moving forward. From each disaster, changes have emerged — new laws, agencies and initiatives designed to improve safety, advance building policies and galvanize community action. Though often tragic, these events have also reshaped the city’s landscape, leaving a lasting legacy.

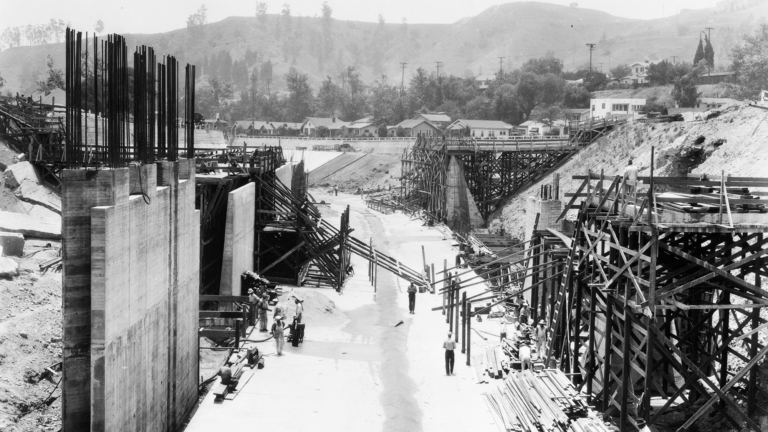

The L.A. River flood of 1938

Back-to-back storms hit Southern California in early 1938, bringing nearly a week of torrential rains that dumped 10 inches in L.A. and upwards of 32 inches in the mountains. The Los Angeles River rapidly exceeded its capacity, sending muddy water and debris throughout the city.

- The San Fernando Valley suffered severe flooding as water rushed down from mountains to the north, and the surging L.A. River flooded areas south of downtown.

- Dozens of bridges were damaged or destroyed by rushing flood waters carrying debris.

- L.A. was cut off from the outside world for days as mud buried roads and railways, and power, gas and communication lines were severed.

- The flood killed 100 people, destroyed about 5,600 homes and caused $70 million (about $1 billion today) in damages.

- The Red Cross fed thousands of evacuees across the L.A. basin. The U.S. Coast Guard ran mail service by boat between San Diego and L.A. and searched the L.A. River for flood victims, finding none.

Lessons and legacy: The devastation spurred action to control flood risks, including channelizing the river and constructing dams.

- The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers oversaw the channelization project, utilizing funding from the Works Progress Administration (WPA) — the largest public works programs in U.S history.

In his words: “Through the major channelization and damming projects of the Army Corps of Engineers in the 1930s, we pretty much put the rivers of the West in a straitjacket. And for very good reason, when you see how damaging these floods can be,” said Will Cowan, who earned his PhD in history from USC Dornsife in 2021 and is now a faculty member at Cal Poly Pomona.

Earthquakes: A way of life

Southern California often conjures idyllic images of sunshine, beaches and movie stars, but it certainly has its faults — literally. One ruptured in 1971 when the magnitude 6.5 San Fernando Earthquake, often called the Sylmar quake, killed 65 people, caused $500 million in damages and exposed critical weaknesses in infrastructure, particularly hospital construction.

- 52 people in hospitals died when the quake struck. At Olive View Hospital, nurses evacuated nearly 500 patients from the collapsed building. Ambulances, buses and other vehicles transported them to county hospitals.

- Thousands of homes in surrounding neighborhoods were condemned.

- The near collapse of the Lower Van Norman Dam on the San Fernando Valley’s north edge prompted the evacuation of 80,000 area residents for three days.

- Even though the Red Cross sheltered 17,000 residents and assisted some 11,000 families, a mass rally two weeks after the quake drew 1,500 people demanding aid and action.

Two decades later, in the early morning hours of Jan. 17, 1994, the magnitude 6.7 Northridge Earthquake killed 72 people, injured more than 9,000, displaced 20,000, caused $60 billion in losses, and disrupted daily life across Los Angeles.

- The I-5 and I-10 freeways collapsed, and damaged roads disrupted daily commutes.

- Several hospitals suffered severe structural damage.

- Tent cities were erected to shelter the more than 100,000 people left unhoused.

- $17 billion was earmarked for quake aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Lessons and legacy: Both quakes led to advances in earthquake preparedness and local and state reforms.

- California’s 1972 Alquist-Priolo Earthquake Fault Zoning Act restricted construction on active faults.

- Building codes were revised to require homes to use plywood to reinforce sheetrock walls, and regulations mandated stronger steel welds to prevent cracks and breaks.

- The U.S. Geological Survey upgraded from analog to a real-time digital seismic network, enabling tools such as Shakemap, which maps ground shaking within minutes to aid emergency response.

“Since Northridge, we’ve addressed many structural weaknesses, but we need better building codes, hazard maps, and faster early warning systems,” said Dean’s Professor of Earth Sciences John Vidale. “Big quakes can set off nearby quakes by redistributing stress onto adjoining faults — understanding the hazard is difficult and critical.”

Civil unrest and the struggle for justice

The 1965 Watts Riots erupted on Aug. 11, 1965, in the predominantly working-class black and poor South L.A. neighborhood of Watts. Sparked by the arrest of 21-year-old Marquette Frye and fueled by outrage stemming from police brutality, housing discrimination and poverty, the uprising lasted six days.

- The Rumford Fair Housing Act, which aimed to end discrimination against people of color, had recently been overturned by Proposition 14.

- The city deployed 934 police officers, 718 sheriff’s deputies and 14,000 National Guard troops.

- 34 people were killed, more than 1,000 injured and nearly 4,000 arrested.

- $40 million in damages were incurred and more than 1,000 buildings were destroyed.

Lessons and legacy: Then-Gov. Edmund G. (Pat) Brown formed the McCone Commission to identify the root causes of the riots. Though few recommendations were implemented by city leaders, there were several local and statewide developments in the wake of the unrest.

- The California Supreme Court ruled Proposition 14 unconstitutional in 1966.

- Budd Shulberg, a novelist and Hollywood screenwriter, created the Watts Writers Workshop, a writing group that inspired literary works about the riots by acclaimed authors such as Thomas Pynchon and Joan Didion.

- USC Dornsife historian Russell Caldwell founded the USC Neighborhood Scholarship Program, now called the Russell L. Caldwell Neighborhood Scholarship Program, to support USC students from the surrounding community.

Following the 1992 acquittal of Los Angeles police officers who were accused of beating Rodney King after a high-speed car chase, Los Angeles erupted in five days of civil unrest and violence.

- More than 50 people were killed, 2,000 were injured and upwards of 1,000 buildings and businesses were destroyed, with damages exceeding $1 billion.

- President George H.W. Bush deployed 4,000 Army and Marine Corps troops to L.A., and they, along with 1,000 officers from the FBI, Border Patrol and other federal agencies, joined state and local police to respond to the uprising.

- For four days, a dusk-to-dawn curfew was imposed on large portions of the city and the surrounding county.

- The L.A. Board of Police Commissioners established the Webster Commission to assess the LAPD’s response to the uprising. Their report, “The City in Crisis,” recommended putting more officers on the street and emphasized community policing, among other efforts.

Lessons and legacy: Like the Watts Riots, the 1992 civil unrest exposed racial and economic disparities but also spurred leaders to action.

- Voters passed City Charter Amendment F, increasing City Hall’s authority over the police chief and expanding civilian review of officer misconduct.

- In 2000, the U.S. Department of Justice ordered a consent decree mandating further reform, requiring the LAPD to track officers’ use of force, arrests and complaints and reform search procedures and community outreach.

- The late Rev. Cecil Murray worked to address the social and economic ills underlying the unrest. In 2004, Murray joined USC at the invitation of the university’s president and provost. Through programs at the USC Dornsife Center for Religion and Civic Culture, he helped faith leaders lead change in underserved communities.

In his words: As pastor of the First African Methodist Episcopal (FAME) Church of Los Angeles, Murray delivered several sermons that both condemned the violence and called out the systemic oppression that sparked them. In one speech, shortly after the unrest ended, he said, “We are not proud that we set those fires, but we’d like to make a distinction … the difference between setting a fire and starting a fire. Those fires were started when some men poured gasoline on the Constitution of the United States of America.”

- Thirty years later, Distinguished Professor of Sociology and American Studies and Ethnicity Manuel Pastor, director of the USC Dornsife Equity Research Institute, said, “The role of systemic inequalities fueled the rebellion.” He added, “Part of it was driven by a reaction to racist policing, in neighborhoods that were twice as poor, twice as unemployed and were about 50 percent Latino …”

The road ahead

Los Angeles has a long history of rebuilding after disasters. As Deverell put it: “The question this time isn’t whether the city will recover from these latest fires — it can and will — but how we will all help shape the future to better withstand the next fire, earthquake or flood.

“We have long claimed to live in the city of the future. We should prove it.”