Not Following the Herd

A newborn goat, umbilical cord still attached, stumbled across the dusty road, bleating in wonder.

From the airplane window a day earlier, eight USC Dornsife undergraduates had watched the Los Angeles sprawl and jammed I-405 vanish before their eyes.

Now they were in rural Ghana.

On the dirt road where the bewildered kid zigzagged his way to a trip of goats, students were greeted by a coterie of children who hung on them, gleefully yelling, “Obruni! Obruni!,” the Twi word for white person, affectionately given to foreigners. The students took a tro-tro — or minibus — to a one-square-mile patch of farmland, where they would live for five weeks investigating agriculture, education and sustainable development in central Ghana.

They were part of USC Dornsife’s first Summer Research Fellowship to Ghana held this year. Blue Kitabu, a nonprofit supporting sustainable education in developing nations, organized the program with the Summer Undergraduate Research Fund (SURF).

Blue Kitabu co-founder Elizabeth Barreras earned her bachelor’s degree in international relations from USC Dornsife in 2007. Wanting to involve her alma mater in the Ghana program her organization started two years earlier, she contacted her former professor, Steven Lamy, vice dean for academic programs in USC Dornsife.

“There are many fragile states in Africa, but health care and education options are improving in places like Ghana,” Lamy said. “Our students have an opportunity to really make a difference.”

Barreras accompanied the fellows on their journey, which resulted in research papers containing recommendations for the Ghanaian government. But before they could offer realistic advice, students had to walk the walk.

Sometimes, literally.

Left: a tro-tro breaks down. Right: fellow Elisabeth Wolfenden leads the way on a narrow bridge. Photos courtesy of Blue Kitabu and Ghana Research Fellows.

“We climbed a mountain,” said Aron Theising, a junior majoring in economics, as if doing so was commonplace. After a tough hike to a waterfall, they felt a sense of accomplishment and closeness.

“So we huddled together and flashed the Trojan victory sign.”

Climb a mountain they did. Theising could have been referring to what this group achieved in five short weeks with never-ending barricades.

“I was really impressed with their guerrilla-like tactics,” Barreras said of the fellows. “They had incredible obstacles when conducting their research. They had to be very persistent and knock on every door. Everyone adapted and rolled with the punches.”

The HIV/AIDS Stigma

Theising, for example, quickly hit a brick wall finding anyone with HIV/AIDS willing to talk. Of Ghana’s 24 million people, 1.8 percent reportedly has HIV/AIDS, but Theising believes the number is higher. He expanded his research analyzing the economic effects of HIV/AIDS in Ghana to include studying the stigma associated with the disease.

When those with HIV decide to tell their communities, he said, many are fired from their jobs, beaten by community members and kicked out of their homes.

“Doctors usually spread the names of people who have HIV,” Theising said. “So someone from Cape Coast will go all the way to Accra, a three-hour drive, to get treatment.”

That is, if that person has travel money. The Ghanaian government subsidizes some HIV medicine, but not transportation costs or treatment for opportunistic infections such as pneumonia. Further, schools are forbidden to educate students about safe sex, but must teach abstinence.

With the help of the Abura-Asebu-Kwamankesie district youth leader, Elvis Donkoh, Theising was eventually able to interview HIV/AIDS patients. They were predominately female because when a woman becomes pregnant, doctors require she be HIV tested.

Elizabeth Barreras ’07 co-founded Blue Kitabu, which provides business models to schools and communities in sub-Saharan Africa to reduce or eliminate aid dependence and promote sustainability. Photo by Alexander Rivest.

“Because of the stigma, men don’t get tested,” Theising said.

The stigma exists even for babies.

Theising recounted one heartbreaking sight. He and Donkoh found an emaciated toddler alone in a house lying on a cement floor, wailing. Neither his mother, nor anyone, could be found. Donkoh, who runs an orphanage, made plans to rescue the child, who was HIV-positive.

“These people don’t have anything,” Theising said. “Still, they have this disease and have to make decisions, or not, to deal with it.”

Harassment in Schools

Four fellows’ research focused on education. Megan Lambert, a psychology and neuroscience double major, studied the barriers to female education in Ghana. Lorenzo Tovar, a senior majoring in philosophy, politics and law, looked at education reform, while Elisabeth Wolfenden, a junior majoring in neuroscience, analyzed the impact of health education in rural Ghanaian schools. James Liu, a senior majoring in philosophy and business administration, researched the performance of Ghana’s business schools.

Lambert learned that most females never make it past junior high school. First there is the cost. Uniforms, textbooks, supplies, registration fees and transportation are too expensive for most families. Faced with educating their children, preference goes to boys.

Fellow Megan Lambert cooks with the locals. Photo courtesy of Blue Kitabu and Ghana Research Fellows.

Her interviews revealed rampant sexual harassment of girls by male students and teacher bias toward boys. By high school, when boys surpass girls 2 to 1, teasing escalates to threats, intimidation and harassment. Girls told Lambert they would rather not eat than face boys in the dining halls calling them “ugly, stupid and bad.”

If a girl refuses sexual advances from a boy, he taunts her in front of his friends and spreads false rumors, Lambert said. Reports to teachers are ignored.

“The students seem to accept harassment as part of life,” Lambert said.

The absence of separate bathrooms for females and males is a major issue. Many girls, especially during menstruation, stay home rather than share a bathroom with boys who will tease them harshly.

“One young woman looked at me incredulously after I asked her questions about sanitation, harassment and teacher bias in school,” Lambert said. “She told me no one had ever talked to her about any of this before.”

The USC Dornsife students sought permission from officials before visiting schools. That may not sound too difficult, but appointments usually involve a four-hour or so window in Ghana. Tovar recalled an official who told him to arrive on Monday morning.

“What time Monday morning?” Tovar asked.

“Just come on Monday morning,” the official replied.

“I would get there, wait and hope he showed,” Tovar said.

The school day, too, started when most of the children arrived. Some youngsters could not afford transportation and had to walk three hours to school. Other children worked mornings and went to school afterward.

In his research, Tovar found that many children whose families cannot afford supplies or the proper uniform skip school for fear of being hit by the teacher. When children are unprepared, the teacher punishes them with a small piece of wood or cane.

Lambert observed this.

“Several students gathered by the windows to see what I was doing in the classroom,” Lambert recalled. “A teacher came out with a stick and started hitting the children away from the windows. They went running trying to escape, and she smacked the slower children repeatedly, rounding them up.”

Upon his arrival, Tovar learned that government funds for supplies often end up in teachers’ pockets.

“After visiting schools, I would get so frustrated I would throw my notebook on the floor and go for a run,” Tovar said. “I didn’t want to deal with it anymore. There are so many obstacles, where do you begin to improve the educational system?”

Later, Tovar discovered that teachers, who earn a meager wage when they do get paid, keep some money because they bring in food for their students who arrive hungry.

“I had to step back and look at the big picture,” Tovar said.

Left: fellows Casey Schmalacker (left) and Lorenzo Tovar sort through the more than 100 books Blue Kitabu donated to the Asuansi Farm Institute. Right: market time in Ghana. Photos courtesy of Blue Kitabu and Ghana Research Fellows.

In her research, Wolfenden found that the Ghana health administration has a good syllabus in place, but it cannot be implemented. Guidelines call for teaching aides to deliver health lessons and nurses to visit schools. But there are no teaching aides or nurses. Each school principal does appoint a health coordinator.

“At some schools, the assigned health coordinator didn’t know he was the health coordinator,” Wolfenden said.

Adding personnel seems an unrealistic luxury when students need soap to wash their hands, Wolfenden said. In addition to teaching aids like books and posters, instructors wished they had dust bins and washing bowls. They told Wolfenden they need computers, DVDs, videos, posters and projectors. But there were more immediate needs. Some rural schools lacked bathrooms and students instead used bushes.

But as West Africa’s fastest growing country, Ghana could one day extricate itself from its status as a developing nation.

“Within the country itself, a good place to begin understanding the Ghana of tomorrow is by studying its soon-to-be middle and upper class: the college-attending population,” Liu said.

Looking at business schools within universities, Liu determined that neither the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, nor the University of Cape Coast have experience, developed infrastructure or an established reputation.

“The University of Ghana-Legon is the obvious 800-pound gorilla,” Liu wrote, “with a well-established brand and Ghana’s only experienced business school.”

Slash and Burn

Divya Rao, an environmental studies sophomore, and Lane Johnston, an international relations sophomore, researched sustainable farming. Staying at the Asuansi Farm Institute, which provides agricultural education, the fellows interviewed teachers and students of aquaculture. They also spoke to University of Cape Coast professors and to farmers.

Rao studied sustainability of tilapia farming because fish supplies about 70 percent of the protein in a coastal Ghanaian diet. To interview farmers, she traveled solo by taxi and tro-tro to the Volta region in eastern Ghana. When the tro-tro driver dropped her off, she panicked.

“It was the middle of nowhere,” Rao recalled.

Finding her way to Lake Volta, the world’s largest artificial lake, she saw workers, young and old, on shore hustling to net fish. Others fished from canoes with treetops in the background poking up from shallower waters. Lugging a bag filled with books and notepads, she found a tilapia farm and sought out the owner.

“It was a real confidence builder,” Rao said. “You don’t know what independence is until you go to a foreign country and travel by yourself.”

Besides teaching Ghanian students in the classroom, the fellows took them on field trips to the beach and other fun places. Photo courtesy of Blue Kitabu and Ghana Research Fellows.

Discovering that subsistence farmers cannot afford to build ponds, Rao recommended that the government set up microfinance operations to provide the initial capital needed.

Johnston investigated deforestation and the hazards of slash and burn — or cutting down plants on a plot then burning it to clear the area for sowing. The practice depletes soil nutrients, threatens animal habitats and leaves the land susceptible to erosion and brushfires.

Climate change due to global warming also adversely affects farmers who rely on rainfall to water their crops, Johnston said. The language barrier made it difficult for Johnston to glean this information from farmers — the subject of one fellow’s research.

Robert Rosencrans, a junior majoring in comparative literature and psychology, had planned to study sustainable agriculture, but after interviewing farmers he focused on the language gap.

Take the term climate change.

“Even with a translator speaking in their native language all you can get is an approximation,” Rosencrans said.

Or organic farming.

“When I asked one citrus farmer of Asebu to define organic, he said simply, ‘We’re not spraying it,’” recalled Rosencrans.

In addition, Ghana has more than 50 languages with some overlap. The Fante and Twi can communicate, for example, because they are part of the Akan tribe. But the Ewe are not and their language differs.

“So how can a researcher, professional or volunteer overcome this challenge?” Rosencrans asked.

In his research, he listed several farming terms — including sustainability — and their meanings in English and various Ghanaian languages.

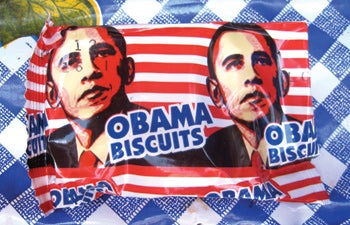

Elephants, Obama Biscuits and Fufu

At night, fellows gathered around a table and recapped their highs and lows of the day. They cherished their visits with villagers, who taught the female fellows how to cook fufu — a staple local food made by boiling cassava root and unripe plantain then pounding the mixture in a large mortar with a long, wooden spoon. Using their fingers, they would dip the fufu into palm nut oil and curries.

The taste?

“Like dough in a broth,” Theising said.

“It’s good with salt,” Rosencrans offered.

President Barack Obama’s image was displayed everywhere in Ghana. Here, cookies are named after him. Photo courtesy of Blue Kitabu and Ghana Research Fellows.

One unusual item was Obama Biscuits, a cookie named after Barack Obama, the first African-American United States president, whose image was displayed everywhere in Ghana.

An unexpected highlight was a walking safari. Unexpected because when they got to Mole National Park, Ghana’s largest wildlife refuge, it was closed. Discouraged, they headed back to the lodge. Then the minibus made an abrupt stop.

“Elephants walked across the road,” Tovar said. “We were feet away from these giant creatures grazing off the trees.”

The lows usually involved water, electricity and tro-tros breaking down. A few weeks into their trip, overgrown bamboo knocked down their power line. They ate dinner using flashlights and walked 15 minutes to gather buckets of cold water for sponge baths. The smallest one in the group, Wolfenden, tried mimicking the locals by balancing the heavy bucket on her head. “It worked,” she said. “Although I did have to hold it with my hands.”

Living for a short time with no electricity, running water, Internet or phones, the fellows learned something new about themselves.

“I was happy, really happy and fine without all of those things,” Wolfenden said.

They had wondered how Ghanaians can seem so content with so little. Now they had an inkling.

Still, this wasn’t their greatest discovery.

Do Something About It

Students grew most excited when talking about how their research may help the people of Ghana. Their recommendations were sent to Ghana’s Ministry of Education, Ministry of Agriculture, the Asuansi Farm Institute and the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology.

Lambert created a detailed awareness campaign for parents, focusing on the practical benefits for educating their female daughters. Wolfenden called for a communitywide approach to teaching about health issues, including the involvement of local radio stations. Johnston recommended farmers start conserving water as a result of climate change.

Rosencrans’ study on overcoming language barriers can become a guidebook for researchers after him.

“At first I thought I should do something concrete in Ghana, like build a school or church,” Rosencrans said. “I felt kind of embarrassed thinking that my research could possibly help.”

He came to a different conclusion.

Read more articles from Dornsife Life magazine’s Fall 2011/Winter 2012 issue