USC ERI & Greenlining Partnership

February 15, 2024

The California Climate Investments (CCI) are turning 10. After a decade of investments and nearly $10 billion implemented throughout the state, is CCI delivering on its promise? Does it drive benefits to environmental justice communities that are the most vulnerable to pollution, have the fewest resources to adapt to climate change, and the least political power to attract these dollars? Do these communities feel the impact of these dollars? In this report, we strive to answer these questions, particularly in light of unprecedented federal funding for climate investments.

Key Findings

- The majority of implemented CCI dollars (73% of the $9.2 billion implemented) are landing in and benefiting Priority Populations which include Disadvantaged Communities (DACs), and low-income communities and households. DACs have received over $4.2 billion (nearly 47% of the $9.2 billion implemented).

- California does not explicitly use a race-conscious approach to delivering climate investments. However, there are statutory requirements around delivering CCI benefits to DACs which are disproportionately Black and Latinx. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that CCI programs are implicitly required to, and are indeed, reaching places with higher percentages of people of color.

- Reductions in co-pollutants such as diesel particulate matter (PM), nitrous oxides (NOx), PM2.5, and reactive organic gasses (ROG) produced by CCI projects were concentrated in the most pollution-burdened communities (top quartile of CalEnviroscreen scores), although these places had the most pollution to begin with, and therefore, the most potential for reductions.

- Most CCI funding is going towards investment types identified as helpful and desired by interviewed environmental justice advocates and leaders (e.g., transportation, housing, urban greening, air quality, solar, water infrastructure).

- Many interviewees were not aware of the suite of programs supported by CCI. At the local level, many interviewed environmental advocates and leaders were not aware of CCI-funded projects in their communities.

- On the other hand, the “felt impact” of investments–the visibility and perceived usefulness and impact of investments to local people– appears strongest when projects are community-driven and well-coordinated (e.g., programs such as Transformative Climate Communities (TCC) and Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities (AHSC)).

- Community groups currently do not have the agency to influence some key aspects of CCI, namely determining how funding is appropriated to different programs and pushing back on unwanted projects.

- “Ease of use” differs across programs, but overall, accessing larger grant opportunities (e.g., TCC, AHSC, Forest Health) is still a challenge for under-resourced applicants, particularly smaller community-based organizations.

- Some problematic projects (e.g., dairy methane digesters, alternative fuels) face continuous pushback from EJ communities for perpetuating inequities and claiming benefits without proper accounting of harms.

- Tribal Communities require tailored offerings, collaboration, and assistance. There is strong sentiment among EJ groups that Disadvantaged Unincorporated Communities continue to be left behind.

- The CCI Detailed Implemented Project Dataset has areas for improvement; advanced data analysis is required to understand many aspects of the data, as well as cumulative outputs landing in communities.

- Philanthropy has a clear and vital role to play in supporting equitable CCI implementation.

- The ecosystem for climate justice in California has made climate investments more equitable, advancing efforts to improve program design, to create specific programs like TCC, and to secure increased funding for Tribal Nations and Indigenous communities.

Lessons for Future Climate Investments

Equity goals matter and must be paired with clear requirements, trackability, and accountability to yield measurable results.

Climate investments produce the most visible, felt impacts when projects are community-driven or have significant community buy-in and involvement.

Climate investments are not neutral. Harmful investments—particularly those that perpetuate fossil fuel infrastructure, false solutions, worsen local pollution, or create harms globally—must be identified and corrected, or defunded.

For equity outcomes, community and EJ groups must have structural influence over climate investments that go beyond engagement (e.g. determining what types of programs are funded, pushing back on unwanted projects).

Ongoing support from the state and philanthropy is needed to ensure communities can easily access and utilize public climate dollars. In particular, defragmenting programs, streamlining and reducing administrative barriers, and providing ample technical assistance should be priorities.

Tribal Nations and Indigenous communities relate to climate investments in their own ways—and investments must tailor support to respect the unique context of these communities.

The ecosystem for climate justice has and will continue to make climate investments more equitable and impactful for communities through power-building, advocacy, community engagement, and project implementation.

Complete data that incorporates community knowledge alongside quantitative statistics is essential for determining and tracking equity outcomes.

The next evolution of climate investment programs can build on previous improvements by producing deeper economic benefits including high-road jobs, supporting community wealth building, and building long-term capacity and power.

In many places, including California, the immense scale of need in pollution-burdened communities likely requires deeper, more reliable funding towards climate justice solutions, including private and philanthropic investments.

Recommendations

From the broader equity analysis, we offer our recommendations to the following decisionmakers.

-

- Create a new funding source exclusively available for use by EJ communities, Disadvantaged Unincorporated Communities (DUCs), and Tribal communities to flexibly address community-identified needs that fall outside the primary scope of CCI goals (e.g., soil remediation, infrastructure, community health, affordable housing development irrelevant to GHG emissions potential).

- Make GHG reduction and local co-pollutant reduction co-equal goals for CCI.

- Commit to reliably funding the strongest climate justice programs–in particular, TCC with ample technical assistance funds.

- Ban the use of GGRF dollars to fund fossil fuel infrastructure and inequitable transition strategies which would apply to dairy digesters for biogas production, natural gas infrastructure, and selected hydrogen projects that are not 100% clean.

- Create a community oversight committee to oversee CCI implementation and weigh in on key aspects (e.g., funding appropriations decisions, development of Investment Plans, Funding Guidelines updates, procedural equity, and reporting and accountability around outcomes–including jobs, environmental, and health benefit outcomes).

- Ban state agencies from requiring waivers of sovereign immunity from Tribal Nations as a requisite for accessing CCI funding.

- Commission a working group composed of relevant state agencies, subject matter experts, and EJ advocates to identify concrete strategies the state can undertake to minimize adverse impacts from domestic and global mineral mining which are being accelerated as a response to California’s clean energy transition goals.

- Allow selected CCI programs to fund work upfront instead of through reimbursement to expand program accessibility for under-resourced organizations, particularly nonprofits.

- Require the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) to determine whether the environmental, health, and economic conditions which represent components of the CalEnviroScreen score are measurably improving in DACs with each subsequent update of CalEnviroScreen. If GHG co-pollutants are disproportionately increasing in places, task CARB with assessing the role and possible shortcomings of the current cap-and-trade mechanism in contributing to disparate geographic outcomes, and identifying avenues to address these.

- Create set-asides for programs created by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and future federal climate funding allocations to California to ensure funds land in and benefit priority communities (i.e., those at the frontlines of the climate crisis, low-income, majority POC communities) in California.

-

- Provide CCI funded users with well-organized, up-to-date, sortable information on opportunities and timelines via CCI websites and calendars.

- Continuously improve CCI reporting by improving output data, neighborhood-scale implemented project mapping, data on benefits to Priority Populations, funding recipient sector and/or demographic data, jobs quality data, and data on successful CCI-related community-benefits agreements or labor agreements.

- In Funding Guidelines, provide more clarity on how the condition “maximize…where applicable and to the extent feasible” can be met by programs for economic, environmental, and public health co-benefits.

- Work with the California Labor and Workforce Development Agency to facilitate a transparent process that allows for labor movement advocates’ feedback on the proposed approach to implementing AB 680.

- Streamline and update benefits criteria tables to reduce the number of possible benefit types and ensure that awarded projects can still claim that benefits to a community or household still significantly outweigh any potential harms, which must also be named.

- Coordinate with all other state agencies working on Tribal support activities (e.g., SGC, CEC, OPR) to collect and coordinate feedback received on Tribal needs and customize program delivery to Tribes.

- Proactively foster dialogue with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), as many California tribes reside on trust lands associated with the BIA and future projects utilizing GGRF dollars may require close coordination with this federal agency.

- Host a discussion between program administrators of selected agriculture CCI programs (e.g., Healthy Soils) and staff from the Department of Pesticide Regulation to identify opportunities to integrate pesticide reduction efforts as a co-benefit into existing program guidelines and relevant metrics that could be tracked.

- On a regular basis, coordinate with state agencies (e.g., SGC) that are working to center DUCs in existing funding programs to identify opportunities to better support DUC communities and to disseminate best practices to other CCI administering agencies.

- On a regular basis, coordinate with state agencies (e.g., SGC, OPR) that are already fostering partnerships with philanthropy to increase community capacity, support community engagement where the state cannot, and to catalyze programs.

-

- Create a clear list and calendar of Justice40 covered programs that can be easily interpreted by different user types and is updated on a regular cadence.

- Develop a definition for “benefits” in collaboration with the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council (WHEJAC), in the context of delivering “benefits to disadvantaged communities.” Any reported benefits should be reflective of both benefits and potential risks including unintended ones.

- Create a data tracking mechanism that will be used by all J40 covered programs to track delivery of benefits; release tracking mechanism for public input on included metrics.

- Create metrics around community engagement to demonstrate the degree to which community members and groups were involved in driving funded projects. Require J40-covered programs to track this metric.

- Require J40-covered programs to track and report on the primary funding recipient type for all projects (e.g., households, companies, community-based organizations, local governments).

- Require J40-covered programs to track and report on whether job quality and job creation requirements were included in program guidelines.

- Release benefits outcomes data from J40-covered programs on a regular cadence that includes information on demographics including race/ethnicity, where possible, and is displayed in a way that helps community understand how investments are flowing to them or not.

- Solicit public feedback on J40 reporting processes and outcomes on a regular cadence; iteratively improve processes and public reporting.

- Support efforts like the J40 Accelerator or Greenlining the Block that prioritize community capacity, particularly in Black and Brown communities that are most vulnerable to climate change.

- Identify possible mechanisms through which to give community members, community-based organization, as well as the WHEJAC more oversight and decision-making power around how J40-covered programs are designed and implemented.

-

- Invest in the long-term strength of member-based organizing institutions who can anchor local collaboratives implementing climate dollars.

- Invest in the leadership of Indigenous, Black, and Latinx climate justice leaders to ensure that those who are experiencing the most harm are leading the way to solutions.

- Support regional collaboratives, like EJ Ready in Los Angeles County and Greenlining the Block, to bring together environmental justice and community-based groups to prepare to receive government funds on their terms.

- While public funding is catalytic, it is rarely enough on its own; the philanthropic sector should finance and fund projects that help close gaps during the planning, pre-development, and implementation phases of using public dollars.

- When public funds are disbursed on a reimbursement basis, take the financial risk off community organizations by funding projects upfront.

- Offer financial capacities to receive funding and allocate it to community groups as a way to support community-driven work.

- Fund opportunities to bring community-based organizations, public agencies, and funders together in a way that uplifts community agency, facilitates relationship building, identifies challenges and barriers around resource delivery, and improves long-term coordination.

- Fund food, childcare, and participation stipends at community engagement events to supplement these activities where public dollars cannot be used.

- Fund community and labor coalition building, so that concerns about jobs and community benefits and risks can be addressed concurrently.

- Fund equity-focused evaluations of climate investments that can contribute to iterative improvements.

10 Years of California Climate Investments: An Equity Analysis and Lessons for this Moment — A panel at the Just Futures Summit 2023

Moderator: Lolly Lim, Program Manager of Climate Investment Research at The Greenlining Institute

Panelists:

- Dr. Jalonne White-Newsome, Federal Chief Environmental Justice Officer, White House Council on Environmental Quality

- Julie Corrales, Barrio Logan Policy Advocate of Environmental Health Coalition

- Leah Fisher, Program Director of Invest In Our Future

- Vanessa Carter Fahnestock, Project Manager at the USC Equity Research Institute

California Climate Investments Program Case Studies

10 Program Case Studies

Dairy Digester Research & Development Program (DDRDP)

The Dairy Digester Research and Development Program (DDRDP) funds the development of dairy digester technologies which captures methane from large manure lagoons and converts it to biogas. This material can be used as transportation fuel or to generate electricity. Since 2015, DDRDP has funded over 130 dairy digester projects, primarily located in the Central Valley. For many years, the program has faced opposition from EJ organizations and local residents. These groups have called out digester technologies as investments that entrench and perpetuate unhealthy livestock management practices which in turn, produce concentrated and unequal burdens in places—air pollution and malodors, extensive water use, and potential water pollution.

Photo credit: Association of Irritated Residents

Community Solar Pilot Program

The Community Solar Pilot Program was another success, that is improving access to clean energy for households unable to benefit from existing low-income solar programs. Through the program, California awarded $2.05 million to a project administered by GRID Alternatives Inland Empire in partnership with the Santa Rosa Band of Cahuilla Indians and the Anza Electric Cooperative that built a community solar system on land leased from the Tribal Nation. Since 2021, the funded project has provided reliable energy access, job training opportunities, and lower energy costs to 38 Tribal households and 162 non-Tribal low-income households. The project is expected to produce more than 42 million kilowatt-hours of energy over the next 20 years.

Photo credit: Santa Rosa Band of Cahuilla Indians

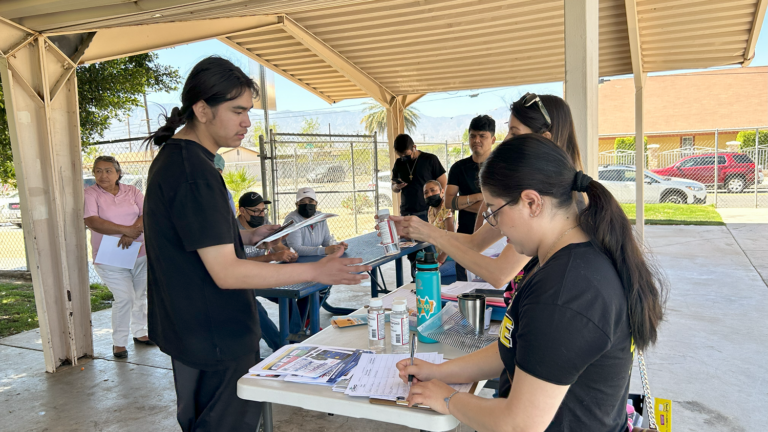

Community Air Protection Incentives (AB 617)

The Community Air Protection Incentives Program (CAP Incentives) was created to support air pollution reduction activities in communities with some of the most concentrated levels of pollution throughout the state—as identified in AB 617 and also known as AB 617 communities. When it comes to centering community priorities and having community members drive decision-making on how incentive dollars are spent, we found mixed experiences. The first two years of the CAP Incentives program funding was spent on vehicle and equipment replacement activities without notable community input. For more recent program years, we heard of positive experiences with participatory budgeting exercises conducted between air districts and local Community Steering Committees.

Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities (AHSC)

The Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities (AHSC) program funds affordable housing and transportation. While the application process is onerous, it includes strong equity guidelines and has produced large-scale, multi-faceted projects, including roughly 15,000 new homes for low-income people, in addition to community-wide benefits like street trees, improved sidewalks, transit infrastructure, and free transit passes. The program has pushed developers to increase community engagement and coordination and improve jobs outcomes. However, several community members and developers representing less dense parts of the state have expressed frustration regarding difficulty accessing funding.

Photo credit: AHSC

Hybrid and Zero-Emission Truck and Bus Voucher Incentive Project (HVIP)

The Hybrid Voucher Incentive Program (HVIP) focuses on transitioning fleets like trucks and buses across the state to cleaner vehicles. Between 2010 and April of 2022, “HVIP has supported the purchase of over 6,000 zero-emission trucks and buses, 2,500 hybrid trucks, 2,400 natural gas engines, and 290 trucks outfitted with electric power take-off.” While it did not start with extensive equity goals, the program funding structure has shifted over time to ensure small fleets and publicly owned fleets can benefit from the program as much as larger private fleets, and that funding prioritizes vehicles domiciled in DACs. Currently, it is estimated that over 60% of HVIP funding has benefited priority communities by locating clean vehicles in DAC or low-income communities. In 2022, 41% of all vouchers were given to public or small fleets.

Photo credit: HVIP

Transformative Climate Communities Program (TCC)

Transformative Climate Communities (TCC) was lifted up across our project interviews as a strong model for funding comprehensive, community-driven climate projects. Through TCC, California has distributed planning or implementation grants to 30 communities, and for this report, we investigated three of these 30 communities—South Los Angeles, Stockton, and San Diego. We found that TCC’s application process ensures applicants engage with community members and trusted organizations to create project proposals that are community-driven. TCC’s strengths lie in the program’s focus on catalyzing local collaboratives and prioritizing tangible progress on climate, health, and economic development projects. However, the high level of technical knowledge, time, and effort required to apply for and report on these funding opportunities remains a significant challenge.

Photo credit: SLATE-Z

Sustainable Agricultural Lands Conservation Program (SALC)

The Sustainable Agricultural Lands Conservation (SALC) Program enables agricultural land owners to enter legal agreements (conservation easements) that protect lands from development in perpetuity. The program also provides funding for technical assistance and planning grants. Through more than eight rounds of funding, 194,000 acres of agricultural land in the state has entered into these trust agreements. The program has made notable efforts to expand eligibility and funding opportunities for Socially Disadvantaged Farmers and Tribal communities. However, few funds from the program have ultimately benefited Priority Populations in direct and meaningful ways.

Photo credit: California Department of Conservation

Forest Health Program

The Forest Health Program was established in 2015 to improve resilience against catastrophic wildfire. According to our interviews, the program has created collaborative multi-jurisdictional partnerships supported by large-sum, flexible funding to awardees. While Forest Health has been a significant touchpoint between CCI and Tribal Nations, there has been tension around this and other state programs that require Tribal entities to commit to a limited waiver of sovereign immunity in order to utilize public funding. Similar to many larger CCI programs, interviewees identified reporting requirements being technically and administratively onerous. Additionally, no job quality standards are required for the program.

Photo credit: Mid Klamath Watershed Council

Low Carbon Transit Operations Program (LCTOP)

The Low-Carbon Transit Operation Program (LCTOP) provides funding to transportation agencies to implement operations or capital projects. The program is guaranteed year-to-year funding from the GGRF (5% appropriation) ensuring reliability. LCTOP dollars are made available on an allocation basis instead of through a competitive process and funding is provided up-front instead of via reimbursement. For any transit agencies whose service area includes a DAC, at least 50% of received LCTOP funds must benefit its DACs. While LCTOP has improved transit in DACs, there have been concerns that this rare source of funding available for transit operations is being diverted towards EV fleet purchases for which there is much more available funding as transit agencies respond to aggressive mandates to transition to zero-emissions vehicles.

Photo credit: MOVE LA

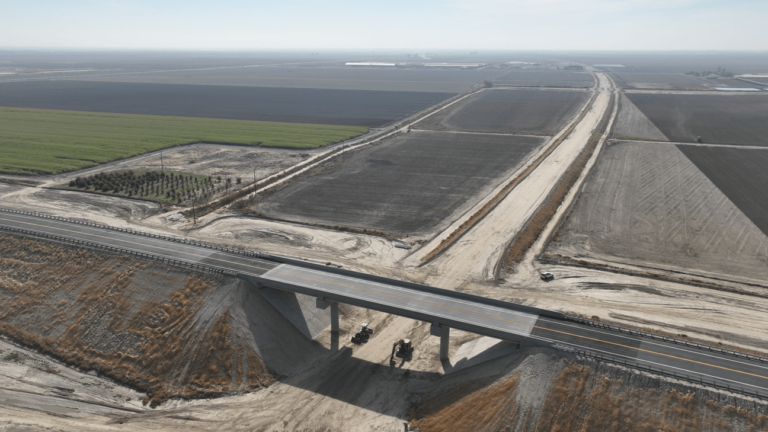

California High-Speed Rail

The High-Speed Rail Project has often been overlooked in analysis because it is so large and still in development. It will be the nation’s first fully electric high-speed rail system and will connect communities across the state. While it is behind schedule and faces escalating costs, HSR has set important workforce and small business goals and produced impressive job outcomes, while building a reputation for addressing community input. Due to its size, we largely focus on HSR activities and impacts in Fresno. Most of our interviewees within Fresno except one were supportive of HSR. However, when it comes to the project’s use of GGRF dollars, we heard critiques from stakeholders within and outside Fresno related to HSR receiving significant and continuous funding from the GGRF (25%) at the expense of other programs that could provide more immediate, tangible benefits.

Photo credit: California High-Speed Rail Authority

Transformative Climate Communities

Transformative Climate Communities (TCC) was lifted up across our project interviews as a strong model for funding comprehensive, community-driven climate projects. Through TCC, California has distributed planning or implementation grants to 30 communities, and for this report, we investigated three of these 30 communities—South Los Angeles, Stockton, and San Diego. We found that TCC’s application process ensures applicants engage with community members and trusted organizations to create project proposals that are community-driven. TCC’s strengths lie in the program’s focus on catalyzing local collaboratives and prioritizing tangible progress on climate, health, and economic development projects. However, the high level of technical knowledge, time, and effort required to apply for and report on these funding opportunities remains a significant challenge. Local philanthropy often plays a critical role filling funding gaps. Despite its excellence, EJ advocates must constantly advocate for TCC to be funded by the legislature–and sometimes do not succeed.

“After consultation with community organizations, TCC expanded program guidelines to include disadvantaged rural and tribal communities as lead applicants. Even with this recent update, program staff are continuously identifying ways to improve and expand accessibility, reflected in our updates to our guidelines.”

Community Conversations

- Dialogues with Communities: Understanding Felt Impacts in Three Places

- Oxnard

- Richmond

- Eastern Coachella Valley

Equitable Climate Investment Principles

Performing an equity-focused analysis of CCI requires a framework against which to measure the initiative’s design, processes, and outcomes. We offer below 10 Equitable Climate Investment Principles (ECIPs) which can serve as guiding principles for use by anyone working to design and implement climate investment programs and projects that center equity. These principles are grounded in the understanding that solutions to addressing climate change must start with equity to be effective.

Equity in the Goals |

Drive with equity from the start, leading with race-conscious solutions that center the most impacted communities. |

Equity in Process |

Center the agency and stated needs of EJ communities, Tribal communities, and other communities (such as disadvantaged unincorporated communities) that have been sacrificed or underserved. Minimize burdens and barriers for priority groups in accessing and utilizing resources. Invest in community organizing, leadership, and capacity building—before, during, and after climate investments are made—to build long-term community power. |

Equity in Outcomes |

Produce desired, thoughtfully coordinated, multi-benefit outcomes for communities on the frontlines of the climate crisis. Make reductions in local pollution burden a co-equal goal and outcome to decreasing GHGs. End the use of all fossil fuels without investing in transition strategies that perpetuate harms or cause new harms to EJ communities. Advance health equity outcomes and at minimum, do not create more harm. Build wealth in EJ communities, including through high roads jobs creation, that can help close the racial wealth gap; at minimum, do not perpetuate economic harms or inequities. |

Equity in Measurement, Evaluation, and Accountability |

Conduct regular equity analyses to ensure transparency and accountability, with a focus on understanding benefits and impacts on communities. |

Acknowledgments

Lead Authors: Lolly Lim (Greenlining) and Vanessa Carter Fahnestock (USC ERI)

Senior Contributing Authors: Alvaro Sanchez (Greenlining) and Manuel Pastor (USC ERI)

Contributing Authors (USC ERI): Austin Mendoza, Cynthia Moreno, Fernando Moreno, Jeffer Giang, and Paris Viloria

Funders: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Open Society Foundations, The James Irvine Foundation, The California Wellness Foundation, and the Bezos Earth Fund.

Download the report

Vanessa Carter Fahnestock, USC Equity Research Institute

Lolly Lim, The Greenlining Institute

Read our other publications by research area

- Immigrant Inclusion & Racial Justice

- Economic Inclusion & Climate Equity

- Social Movements & Governing Power

- Publications Directory