Building Political Power Among Asian American Immigrants Through Naturalization

Kamala Harris’s groundbreaking presidential nomination as the first Black and South Asian American to lead a major party ticket has energized the Asian American community, who could be key swing voters in 2024. According to The Hill, there are more eligible South Asian voters in Michigan, Georgia, and Pennsylvania than the margin of victories in the last presidential election.

Asian Americans are the fastest growing racial group, and consequently, the fastest growing voter bloc in the U.S. Considering that 71% of Asian American adults are immigrants, increasing naturalization rates in this racial group is crucial to supporting their political integration in the pursuit of a more representative, democratic society. In fact, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) face the greatest political underrepresentation as elected officials compared to other racial groups. Though AAPIs represent 6.1% of the nation’s population, they make up only 0.9% of elected leaders. Immigrants’ political inclusion and civic engagement in the U.S. are limited if they lack U.S. citizenship, which is necessary for the right to vote and run for office.

In 2018, Asian American immigrants made up nearly 4 out of every 10 naturalized immigrants, making them the most likely racial/ethnic group to naturalize, compared to immigrants from South America, Central America, Mexico, Africa, Europe, and Oceania. However, these high naturalization rates mask the diversity of Asian American immigrant experiences. For example, while immigrants from Vietnam (76 percent) and Cambodia (81 percent) have naturalization rates well above the average for all immigrants (52 percent), immigrants from Japan (34 percent) and Nepal (36 percent) are naturalizing at much lower rates.

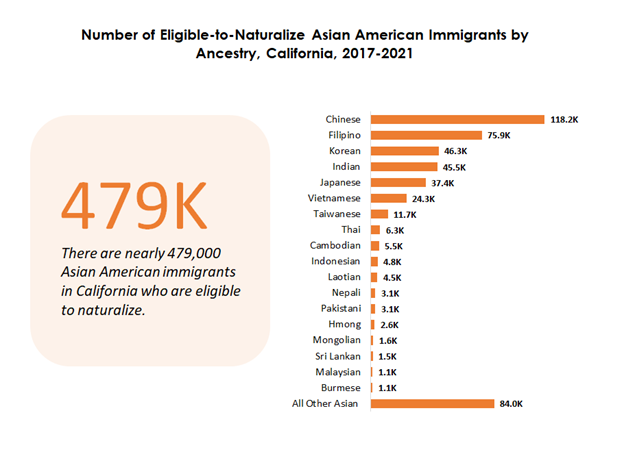

Our research report, Asian American Immigrant Inclusion in California: Citizenship, Community, and Policy, estimates that there are nearly 479,000 Asian American immigrants who are eligible to naturalize (ETN) in California, a state where “the growth of eligible AAPI voters…in the last decade was more than double the growth of the statewide eligible voting population.” In the figure below, the ETN Asian American immigrant population in California is broken down by ancestry, showcasing the political opportunity of increasing naturalization rates across all Asian groups.

To increase naturalization rates among Asian American immigrants, we must address barriers to naturalization, including the rising costs. The application fees for naturalization have increased over time, now costing $760 for a paper filing or $710 for online filing. However, immigrants with annual household incomes not more than 400% of the Federal Poverty Guidelines are eligible to apply for fee waivers, which reduce application costs to $380. A research study revealed that the fee waiver expansion in 2010 increased naturalization rates among lower-income immigrants, demonstrating the importance of lowering fees to reduce barriers to naturalization.

The cost of becoming a U.S. citizen often extends beyond official fees, as some immigrants may need assistance in preparing the application or attending English and civics classes to study for the naturalization exams. Paying for application assistance is common among immigrants with limited English proficiency, as heard in our interviews with service providers at community-based organizations (CBOs). CBOs provide critical naturalization services to Asian American immigrants, often meeting demands that public agencies struggle to address in serving diverse communities. While CBOs often serve clients at no cost, our interviews revealed that they face a variety of challenges in serving Asian American immigrants, such as the impact of fee-for-service intermediaries. During our research, we found that some Asian American immigrants turn to co-ethnic third-party intermediaries for application assistance, potentially putting them at risk of costly scams and/or illegitimate services. Sofia (pseudonym used), who works at a CBO primarily serving South Asians, shared her experience working with clients who rely on intermediary services:

I had one client who’s going to an accountant, who is kind of like the attorney for the community, because everybody trusts him, but he’s not helping anybody. He’s just taking their money and letting a case sit for years and years and clients are just thinking, “Oh, no, no, no – I paid him so much. He’s going to help me. He’s gonna help me.” Clients will trust people and attorneys that they pay a lot of money to, versus, as a nonprofit, we don’t charge them. They barely trust us sometimes and sometimes they’ll question me.

The challenges of building trust with Asian American immigrants was frequently brought up during our interviews. Asian American immigrants who are unfamiliar with nonprofit organizations’ “doing-it-for-free” model may prefer those who charge a fee, believing higher costs indicate higher quality services. Furthermore, our interviews revealed that immigrant clients may prefer co-ethnic intermediaries over nonprofit service providers because they are seen as more linguistically and culturally similar, and thus more trustworthy.

Another common barrier to naturalization for Asian American immigrants is the difficulty of the required English and civics exam. This is especially true for lower-income Asian American immigrants who don’t have the time to attend courses and study for the exams. Natalie (pseudonym used), who works closely with Thai immigrants shared:

I’ve had a lot of clients who prepared the naturalization application, but they cannot pass their English language and civics exam and they had to go in multiple times, still do not pass. And this is a real barrier, I think, especially for folks who live in ethnic enclaves that work full time […] These are people that work seven days a week and there’s no options. They want to make money, so that they can raise their kids and then their kids can do those things.

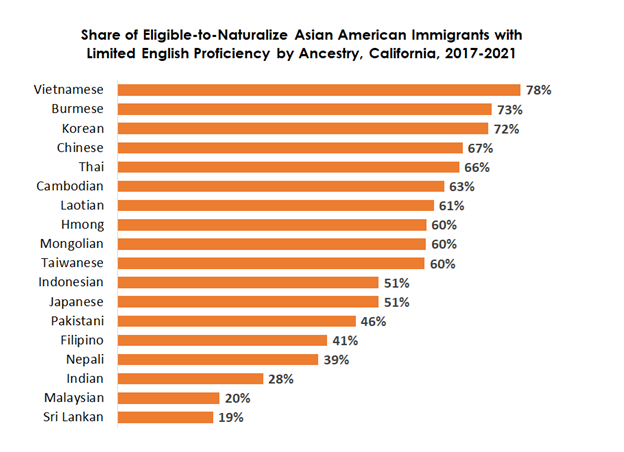

As seen in the figures below, the rates of limited English proficiency among ETN Asian American immigrants vary greatly depending on ancestry.

However, even though the figure shows Filipino American immigrants with lower rates of limited English proficiency, there are variations within the group itself, as seen in Leslie’s statement:

[The] Philippines has five national languages, plus English. If you’re formally educated, you would have had access to two or more languages, including English. But if you didn’t, which is [the case for] a lot of the new immigrant communities [who] are not formally educated, they only have their native language, which isn’t usually the five.

Overall, while disaggregating Asian American immigrant data by ancestry is important, there is also a need to investigate the differences within ancestry groups. Just as Asian Americans are not a monolithic group, neither are Filipinos, Indians, or any other ancestry group. Within each group, the combination of certain barriers and drivers of naturalization can shape immigrants’ choice and ability to naturalize in different ways. For example, Ivy shares how her Vietnamese clients value citizenship differently depending on their age and class:

Based on [my] personal experience, 10 years ago, I see a lot of people come here, as international students or through sponsorship, they would put naturalization as the top, the main reason that they want to stay here. […] Recently, I met a lot of later generations […] even though they’re international students, they have shared with me that it’s okay for them to go back [to Vietnam]. […] Mainly because I feel like in Vietnam, everything is improving […] But at the same time, I feel like even though there’s a slight shift like that, it only applies to people who are middle-class or a little bit higher class. For people who are lower income, they would prioritize staying here as the main purpose [of naturalization].

In our report, we explore the drivers and barriers of naturalization for Asian American immigrants and how they are differentiated across subgroups. Our research report dives deeper into the intersectional experiences of Asian American immigrants, in terms of labor, gender, family circumstances, place of residence, as well as policies and conditions in immigrants’ country of origin. Furthermore, the research report shares recommendations for CBOs, policymakers, and philanthropic funders to increase naturalization rates among Asian American immigrants and support their political integration for a more representative democracy.

In our report, we explore the drivers and barriers of naturalization for Asian American immigrants and how they are differentiated across subgroups. Our research report dives deeper into the intersectional experiences of Asian American immigrants, in terms of labor, gender, family circumstances, place of residence, as well as policies and conditions in immigrants’ country of origin. Furthermore, the research report shares recommendations for CBOs, policymakers, and philanthropic funders to increase naturalization rates among Asian American immigrants and support their political integration for a more representative democracy.

Acknowledgments

The research for the Asian American Immigrant Inclusion in California: Citizenship, Community, and Policy report was conducted by Thai V. Le, Shannon Camacho, Chuchen (Eden) Pan, and Alicia Võ.

This research is a collaborative effort with our invaluable research partners, who are providing important on-the-ground services and advocacy to support immigrant inclusion in California. The USC Equity Research Institute (ERI) would like to thank all our research partners who participated in surveys and interviews to share their lived experiences, successes, and challenges.

We extend our gratitude and appreciation to the team of researchers, analysts, communications staff, and designers who provided crucial support throughout the project: Jeffer Giang, Jennifer Ito, Sabrina Kim, Joanna Lee, Edward Muña, Rhonda Ortiz, Manuel Pastor, Cristina Rutter, Justin Scoggins, Paris Viloria, Debora Gotta, and Gladys Malibiran.

This research was funded by AAPI Data with support from the California API Equity Budget. We would like to thank Whitney Ibarra, Fontane Lo, and Karthick Ramakrishnan from AAPI Data for their support in facilitating the funding and helping to shape the vision of the research at its inception.

About the author:

Alicia Võ (she/her) graduated from the University of Southern California with an MA in Sociology and her thesis analyzed the effect of regional racial demographics on the potential for multiracial coalition, focusing on Asian American communities. Before graduate school, she attended Harvey Mudd College and received her BS in Computer Science and Asian American Studies. During college, she conducted computer science research in natural language processing to evaluate children’s oral reading skills. Afterwards, she did human-centered design research to preserve indigenous health practices in Vietnam. Her variety of experiences reflects her love for learning and inherent curiosity of the world. Alicia worked at the Equity Research Institute as a graduate student and will be transitioning to a Research & Data Analyst position at Catalyst California. In this next stage of her career, Alicia is excited to conduct community-engaged research and envision improved governance models for social change.

Alicia Võ (she/her) graduated from the University of Southern California with an MA in Sociology and her thesis analyzed the effect of regional racial demographics on the potential for multiracial coalition, focusing on Asian American communities. Before graduate school, she attended Harvey Mudd College and received her BS in Computer Science and Asian American Studies. During college, she conducted computer science research in natural language processing to evaluate children’s oral reading skills. Afterwards, she did human-centered design research to preserve indigenous health practices in Vietnam. Her variety of experiences reflects her love for learning and inherent curiosity of the world. Alicia worked at the Equity Research Institute as a graduate student and will be transitioning to a Research & Data Analyst position at Catalyst California. In this next stage of her career, Alicia is excited to conduct community-engaged research and envision improved governance models for social change.