Linguistic Diversity and Support for Multilingual Spaces for Asian and Black Immigrants

California is home to a myriad of immigrant communities that enrich the state’s demographic and cultural fabric. To enhance immigrant livelihoods, data-driven insights are vital for identifying needs, improving services, and informing policy decisions. The California Immigrant Data Portal (CIDP), launched in 2020, offers insights into the state’s immigrant population, measuring economic mobility, warmth of welcome, and civic participation. Leveraging data from federal, state, and local sources, the portal, updated in October 2022, delivers comprehensive macro and micro-level data disaggregated by immigration status, race, and language. This blog post showcases data and analysis featured on the new languages spoken indicator on CIDP by spotlighting the linguistic diversity and language access needs within Asian and Black immigrant communities. The languages spoken indicator provides a closer look into the varying experiences of immigrants from different racial backgrounds throughout the state.

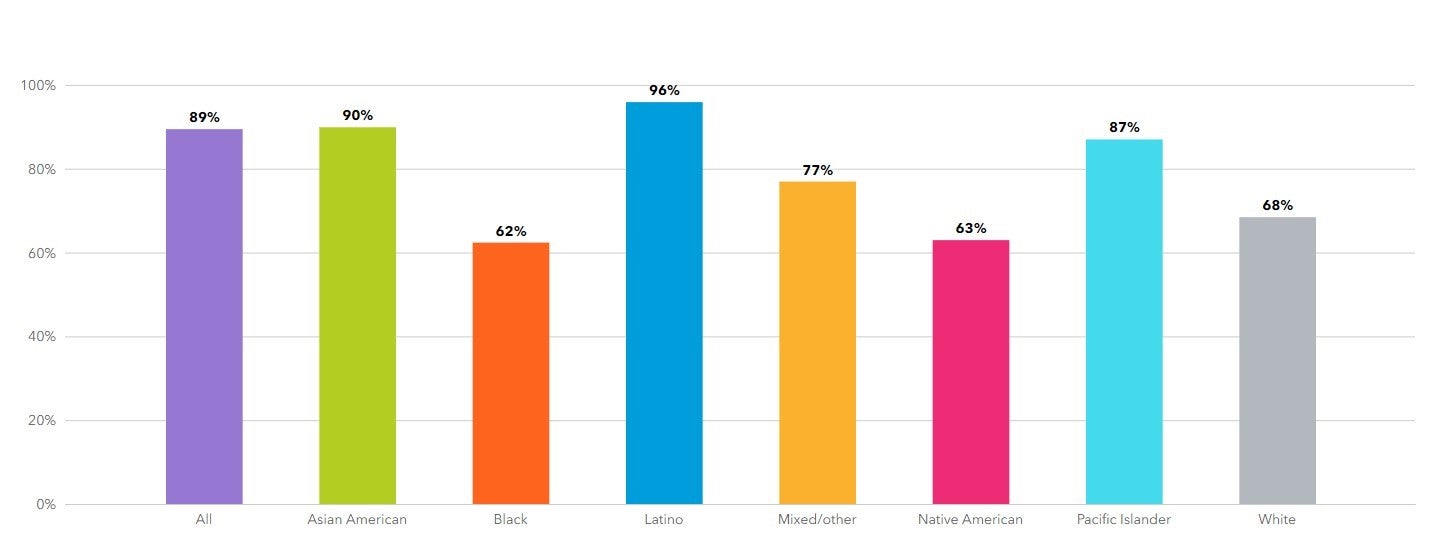

Data Highlight #1: 90% of Asian American immigrants in California spoke a language other than English at home in 2019.

Nearly 5.6 million Californians identified as Asian American in 2019, comprising about 14% of the state’s population. In 2019, 75% of all Asian American Californians spoke a language other than English at home, as compared to 45% of all Californians. Moreover, 90% of Asian American immigrants spoke a language other than English at home (see Figure 1 below). Chinese, Tagalog, Vietnamese, and Korean were among the top 10 Asian languages spoken by immigrant Californians in 2019, with over 2.4 million speakers. South Asian languages such as Hindi were also among the top 10 languages spoken by over 175,000 immigrant Californians. Other languages spoken by immigrants such as Panjabi, Urdu, Marathi, Kannada, and Gujarathi are also visible in the language spoken indicators, demonstrating the linguistic and ethnic diversity of the state. It is also important to highlight the geographic diversity of Asian languages spoken throughout the state. For example, Hmong was one of the top 10 languages spoken among immigrants in places like Butte and Fresno Counties in 2019.

Figure 1. Percent of population ages 5 or older who speaks a language other than English at home by race and immigration status, California, 2019

Source: USC Equity Research Institute analysis of the 2019 American Community Survey 5-year samples from IPUMS USA. Note: Data for 2019 represent a 2015-2019 average. The number and percentage of people ages 5 or older who speak a language other than English at home by race, nativity, and immigration status; and the top non-English languages spoken at home. Data from For more information, visit the California Immigrant Data Portal, https://immigrantdataca.org/indicators/languages-spoken?breakdown=by-race&immig=2.

Despite having a sizeable presence throughout the state, Asian immigrants grapple with critical language access challenges such as a shortage of interpreters for Asian languages and a lack of culturally responsive services. Just one example highlights the scarcity of qualified translators for Asian workers that can create barriers for workers to file health and safety concerns in the workplace. An analysis of inspectors employed by California Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA), revealed that in California there was only one bilingual inspector that was fluent in Cantonese, despite the approximately 309,000 workers that speak Cantonese and have limited English proficiency. Further, only one bilingual inspector was fluent in Vietnamese, even though about 167,500 workers who speak Vietnamese have limited English proficiency. These language gaps hinder access to fair and safe working conditions. AAPI immigrants also confront alarming barriers in accessing healthcare and legal services, where their needs have been largely overlooked, undermining the well-being of these communities.

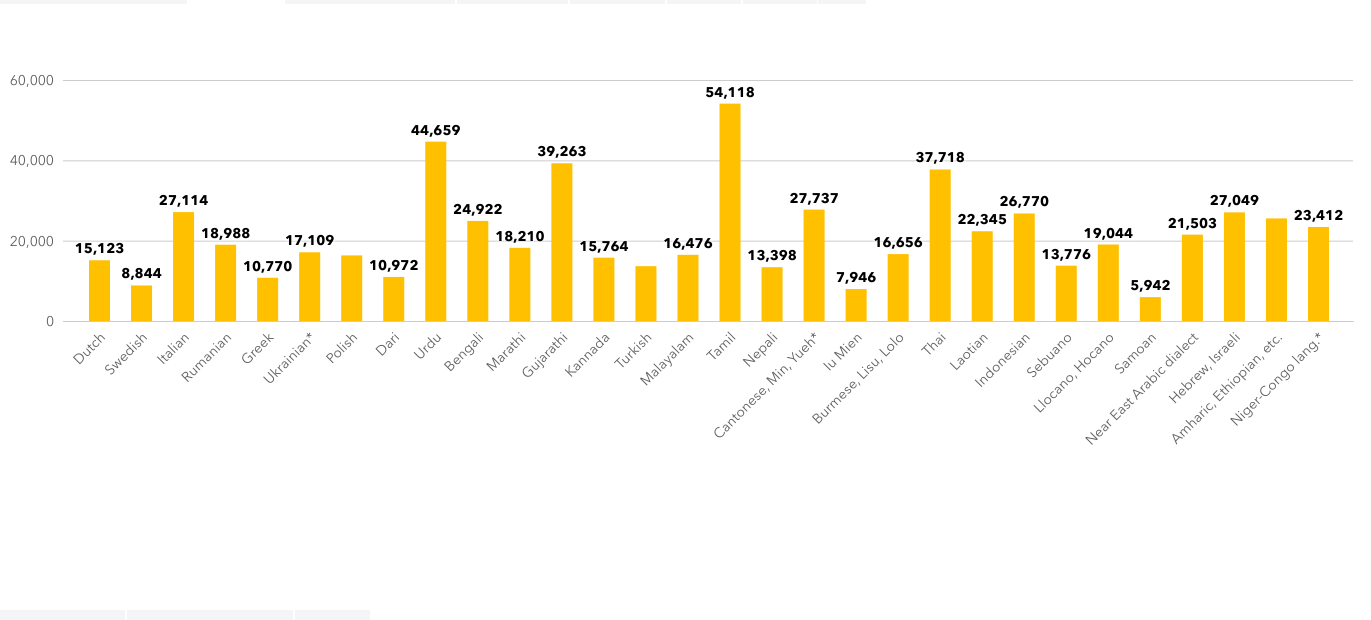

Data Highlight #2: Amharic, Ethiopian, and Niger–Congo languages are among the most spoken languages by immigrants in California in 2019.

In 2019, about 8% (or 165,000) of Black residents in California were immigrants. While many immigrants hail from Africa, others come from Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central America, facing dual marginalization as Afro-Latinos. The languages spoken indicator on CIDP shows that 62% of Black immigrants in California spoke a language other than English at home in 2019. Black immigrants form a highly diverse collective. Indeed African and Caribbean immigrant populations speak about 2,100 languages and dialects. Amharic, Ethiopian, and Niger–Congo languages rose among the most spoken languages by immigrants in California in 2019 (see Figure 2 below). In places like Los Angeles and San Diego Counties, French or Haitian Creole and Swahili, arise among the most spoken languages, respectively, highlighting the geographic diversity of languages spoken by Black immigrants throughout the state.

Figure 2. Top 21st to 50th languages other than English spoken at home by immigration status, California, 2019

Source: USC Equity Research Institute analysis of the 2019 American Community Survey 5-year samples from IPUMS USA. Note: Data for 2019 represent a 2015-2019 average. The number and percentage of people ages 5 or older who speak a language other than English at home by race, nativity, and immigration status; and the top non-English languages spoken at home. Data from For more information, visit the California Immigrant Data Portal, https://immigrantdataca.org/indicators/languages-spoken?breakdown=top-languages&immig=2&top_lang_group01=03.

Acknowledging the linguistic diversity among Black immigrants is as important as addressing the disparities in language access that persist. A report by the Black Alliance for Just Immigration (BAJI) titled, Black Lives at the Border, uplifts the stories and outlines recommendations for improving the conditions of recently arrived Black immigrants and refugees. One story highlights the case of Anabelle, a Haitian migrant and mother of six, who migrated to the U.S. due to economic hardship caused by the earthquakes in Haiti. Before arriving in San Diego at the U.S. border, Anabelle traveled from Haiti to the Dominican Republic, Brazil, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Mexico. Anabelle did not have access to immigration translation services in Haitian Creole, an experience faced by many other immigrants of African descent. As a result, Anabelle could not attend her assigned court appearance and, in her absence, was given a deportation order. These language gaps hinder access to critical legal services that can make a difference in the outcomes for immigrants fleeing precarious circumstances. Moreover, these language access gaps also impact access to other critical needs such as access to health services.

Conclusion

Asian and Black immigrants are part of California’s ethnic and linguistic diversity that should be seen as an asset. The data provided in the languages spoken indicator showcases the linguistic diversity of the state across distinct languages, different immigrant groups, and different geographies. Equally as important is recognizing that language access is a human right and critical to understanding the lived experiences of Asian and Black immigrants that can guide forward-thinking policies, services, and research tailored to diverse immigrant communities. To learn more, view a demo of CIDP, and stay up to date on data updates, visit our site here: https://dornsife.usc.edu/eri/research/california-immigrant-data-portal/. To explore the languages spoken indicator, including data, insights and analyses, and case studies, visit CIDP here: https://immigrantdataca.org/indicators/languages-spoken.

Blog co-edited by Gladys Malibiran, ERI Communications Manager

© 2023. This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.