“Port of Long Beach by Don Ramey Logan.jpg from Wikimedia Commons by D Ramey Logan, CC-BY-SA 3.0”

21. The LA-LB Harbor Safety Committee

Author: Dr. James A. Fawcett, USC Sea Grant Maritime Policy Specialist/Extension Director (retired)

Media Contact: Leah Shore / lshore@usc.edu / (213)-740-1960

In our huge, busy seaports, it is probably no surprise that safety is a top priority. But who’s in charge? There are multiple layers of safety provided by both seaports in Los Angeles. Both ports have port police agencies, as well as the U.S. Coast Guard for matters on the water. However, on an issue as important as safety, thorough protection can best be secured by working with committees that represent the needs and interests of the many industries, businesses, government agencies, and the public that jointly use the resources of our seaports. Two committees are particularly notable for us: (1) the Area Maritime Security Committee (AMSC), consisting of representatives from federal, state, local, and seaport law enforcement, and (2) the Los Angeles-Long Beach Harbor Safety Committee (LA-LB HSC).

Area Maritime Security Committee (AMSC)

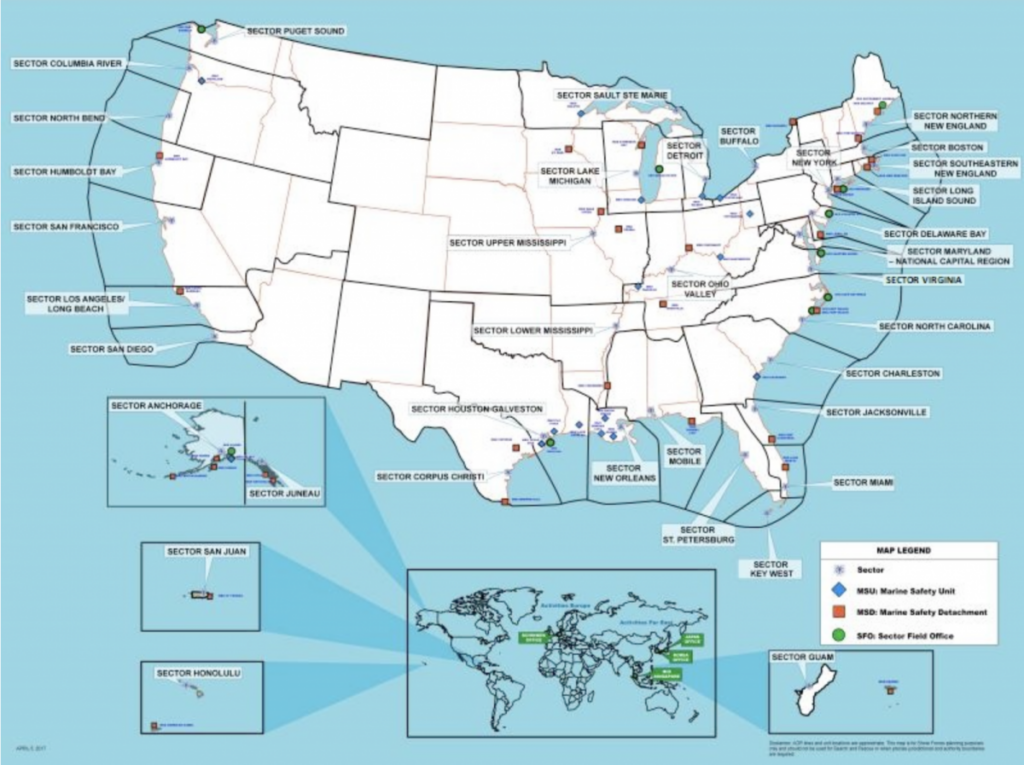

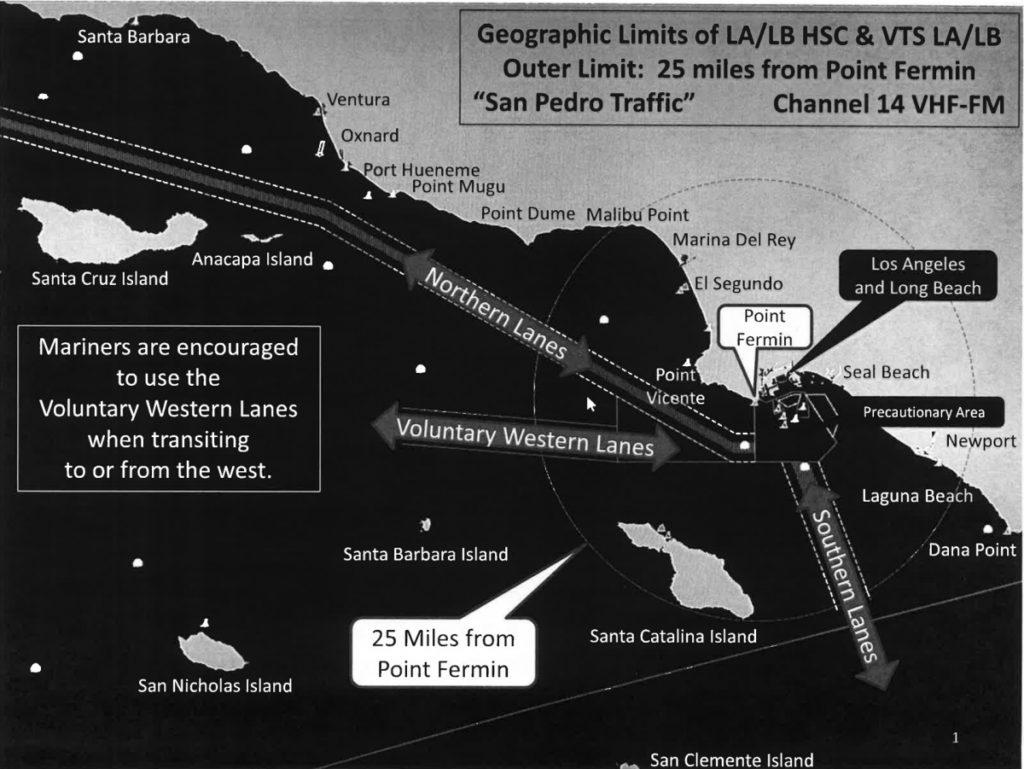

The AMSC is authorized by the Maritime Transportation Security Act of 2002[1] to provide coordination between the various law enforcement agencies noted above. While organized by the U.S. Coast Guard Captain of the Port[2], the AMSC is governed by a charter written by its members. It is responsible for both the physical security of ports and harbors and also for the cybersecurity of these facilities. Maritime security committees are established nationwide to secure the 361 public ports in the U.S., especially for the 25 ports which pass 98% of all containerized marine freight. Each committee meets at least once a year in this effort (in LA, they meet four times per year). Working together, these agencies develop security plans mandated by the federal statute and are implemented on a regional basis. In Southern California, the AMSC is organized, developed, and maintained by Sector Los Angeles-Long Beach (LA-LB) of the U.S. Coast Guard. The AMSC for our region is well established and has functioned effectively for the past 20 years, organizing communications and cooperation among the many marine and mainland agencies, emergency command centers, and state and federal law enforcement jurisdictions under one umbrella on behalf of maritime security.

Los Angeles-Long Beach Harbor Safety Committee (HSC)

The second of these two coordinating committees is the LA-LB Harbor Safety Committee, consisting of a large group of stakeholders who utilize port facilities for their common benefit. And what a group it is! Organized under the auspices of the California Department of Fish & Wildlife Office of Oil Spill Prevention and Response (OSPR), similar to the AMSC, it is chartered by the voluntary coordination of its members (see membership list below). On the commercial side of the committee are stakeholders representing the vessels handling marine freight, both in bulk and containers. On the non-freight side are stakeholders representing recreational boaters, fishers, cruise vessels, scenic tour vessels, tugs and barges, pilot boats, ship repair facilities, commercial fish markets with their fleets of fish boats, and shoreside facilities of all types. Coordinating this large group of users can best be achieved by inviting representatives from each group to join the discussion to resolve and prevent use conflicts in the two harbors.

Oil Pollution Act (OPA 90)

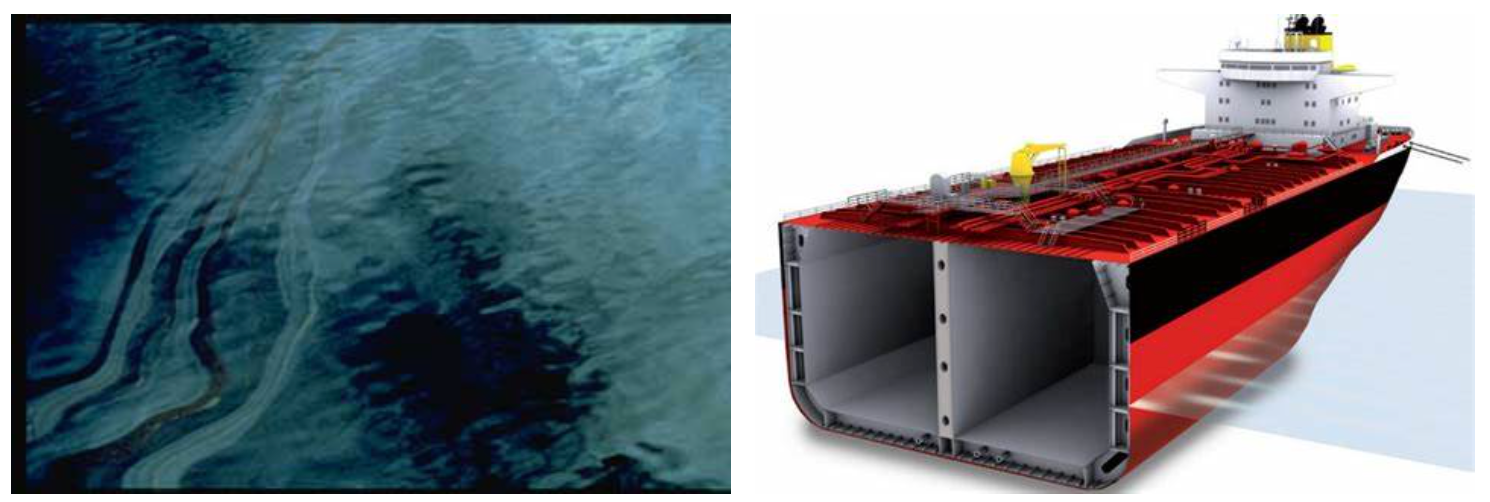

In the spring of 1989, the Exxon Valdez oil spill occurred when the tanker spilled 11 million gallons of crude oil at Prince William Sound in Alaska. This event inspired the US Congress to consider why the accident happened and what could be done to prevent future similar disasters as oil from the North Slope of Alaska was transported south to the lower 48 states. Responding rapidly the following year, it enacted the Oil Pollution Act (OPA 90), an amendment to the Clean Water Act that applied to all US waters[3]. Among other things, such as mandating double-hull tankers, setting new requirements for vessel manning and watchkeeping, mandating contingency planning, enhancing federal response capability, and increasing penalties for spills, OPA 90 established the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund (OSLTF) for “up to $1 billion to pay for expeditious oil removal and uncompensated damages up to $1 billion per incident.”[4] By 1990, the US Coast Guard has delegated the responsibility for administering the OSLTF through a new office, the National Pollution Funds Center (NPFC).

Lempert-Keene-Seastrand Oil Spill Prevention and Response Act

The provisions of OPA 90 apply only to spills in federal waters, yet because of its dependence on oil transported into the state from Alaska and foreign sources, the California Legislature in 1991 sought to similarly protect state waters from oil spill incidents by enacting the Lempert-Keene-Seastrand Oil Spill Prevention and Response Act.[5] This act established the California Office of Oil Spill Prevention and Response within the Department of Fish and Game (now the Department of Fish and Wildlife). Implementation of its provisions are defined under the California Emergency Services Act[6]. Section (a) of the latter states its rationale:

Each harbor safety committee established pursuant to Section 8670.23 shall be responsible for planning for the safe navigation and operation of tank ships, tank barges, and other vessels within each harbor. Each committee shall prepare a harbor safety plan encompassing all vessel traffic within the harbor.[7]

Subsequent provisions of the act state how the HSCs shall be organized and managed. The law empowers HSCs at Humboldt Bay, San Francisco Bay (including San Pablo and Suisun Bays), Port Hueneme, Port of Los Angeles/Port of Long Beach, and the Port of San Diego.[8] In each port, the HSC is required to develop and continually review and modify as necessary a harbor safety plan “encompassing all vessel traffic within the harbor.”[9]

The emphasis of the act is on oil spills, movement of vessels carrying oil cargo, and rules for maneuvering those vessels in the named seaports, as stated in the following:

A recommendation determining when tank vessels are required to be accompanied by a tugboat or tugboats of sufficient size, horsepower, and pull capability while entering, leaving, or navigating in the harbor. The Harbor Safety Committee for San Francisco shall give the highest priority to the continual review and evaluation of tugboat escort regulations. The administrator shall be guided by the recommendations of the harbor safety committee when adopting regulations pursuant to Section 8670.17.2.[10]

Los Angeles/Long Beach Harbor Safety Plan. Source: Marine Exchange of Southern California

Concerns for Large Vessels

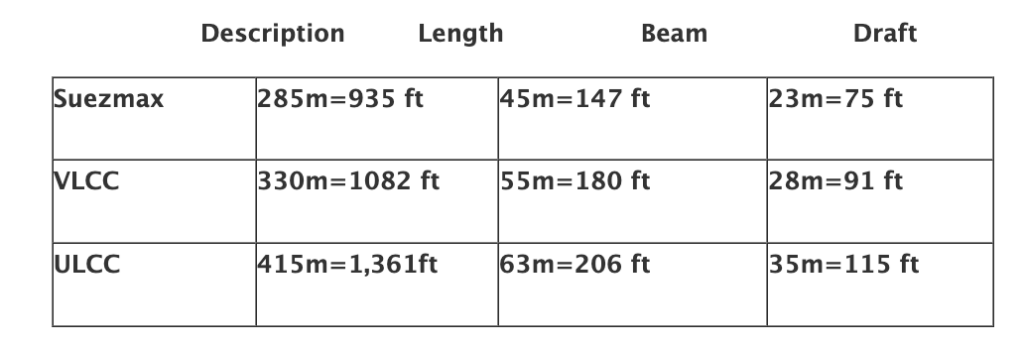

Tankships (tankers), especially large crude oil tankships that are referred to as VLCCs (very large crude carriers) or ULCCs (ultra large crude carriers) present a variety of maneuvering challenges when entering or departing from California’s harbors.

Consider the following graphic showing The Sizes of Large, Crude Carrying Tankships:

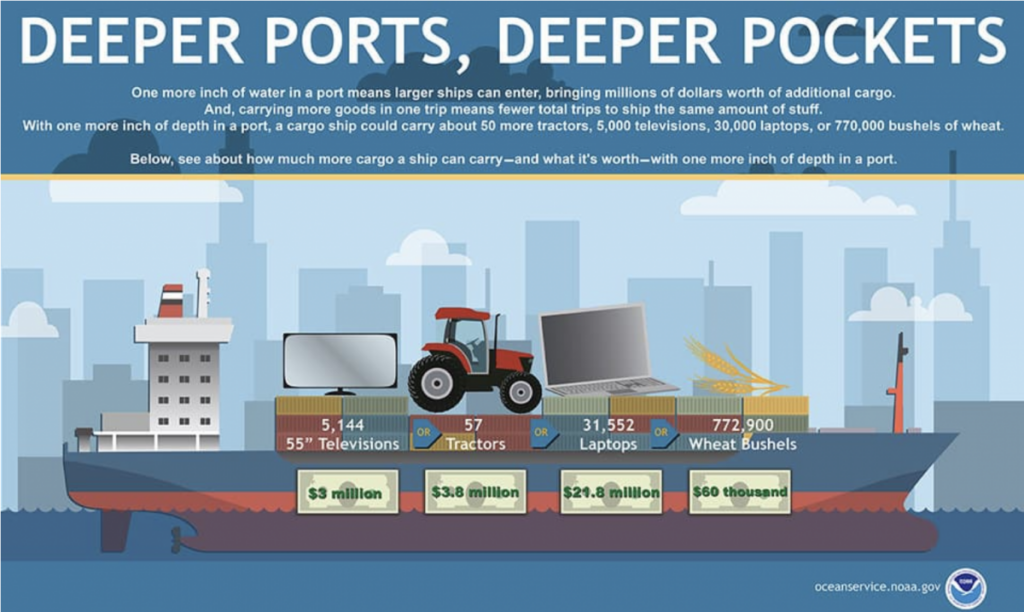

Channel Depth Limitations

The table above illustrates various sizes of larger crude carriers that exist and serve ports across the globe. Although our two ports can accommodate many vessels, they cannot handle some of the large vessels above due to vessels being limited by their draft. This is because the Port of Long Beach can only accommodate tank vessels with a draft (depth) of 69 feet or less. Generally, vessel classes have names descriptive of their size, indicating their ability to pass through important narrow channels worldwide. Thus Suezmax describes the largest crude carrier that can pass through the Suez Canal (similarly, smaller ships are designated as Panamax or Aframax, etc.).

Hazards from Wind

The issues posed by these huge ships are not merely limited to their cargo and their sizes through channels but also how they behave in oceans and harbors. For example, the large slab-sided hulls of container, vehicle, and passenger ships can act like the sails of a sailboat, catching the wind and causing the ship to be pushed sideways; and their large size does not eliminate this effect. In fact, despite their displacement and overall mass, these 1000-1200-foot-long ships have huge amounts of sail area when wind affects it from the side (abeam). While not such an issue at sea, when one of these huge vessels comes into a port with obstructions nearby, wind can create a major hazard both for the ship and its nearby obstacles.

Tank ships up to 1,100 feet long can enter the port of Long Beach. When arriving loaded and sitting deep in the water, these ships are affected more by the current than the wind. However, when departing empty, they sit high in the water and are more vulnerable to wind. In another respect, their length and tendency for fore-and-aft pitching (porpoising) creates issues in harbors; the draft of these vessels extends so far underwater that often the keel (bottom-most longitudinal plate on a ship extending from bow to stern) of the ship is only a few feet from the bottom of the harbor. As a result, for a vessel with over a 1,100-foot distance between bow and stern, just one degree of pitch creates 10 feet of up-and-down movement of the ship from bow to stern. This can mean that either the bow or stern can strike the bottom of the harbor, causing it to incur hull damage. If the damage is severe, it could result in a spill. From the perspective of OSPR, the state and the ports have a distinct interest in maintaining safety for these behemoths of the seas. The good news is that the Harbor Safety Plan contains guidelines for acceptable under keel clearance to help prevent groundings.

Ensuring Safety Beyond Oil Spills

Beyond ensuring the safety of vessels carrying petroleum products, the HSCs are concerned with creating a hazard-minimized environment for all vessels, including reducing or eliminating navigation hazards, noting collisions and allisions[11] (for lessons learned), tracking vessels anchored, noting harbor maintenance activities such as dock work, dredging, unusual vessel operations, and coordinating safety issues with both harbor departments, especially with any new developments or activities not previously noted in the current harbor safety plan.

Diversity of HSC Membership

Important as the crude carriers are, they do not make up the majority of the vessels in our ports. In fact, containerships constitute a larger proportion of vessel traffic, but they also must share the waters with bulk carriers, car/truck carriers, ferries, fishing vessels, Coast Guard and US Navy vessels, and pleasure craft. In this mix, the HSCs are established to facilitate coordination and consultation between all port users; the harbor safety plans set forth rules for those interactions and acknowledge the diverse needs of a multitude of users. Fostering that goal, representatives of the various groups of users are represented on the HSCs. The Los Angeles/Long Beach HSC is a good example of this diversity. Its members represent the interests[12] below:

| Voting Members | Non-Voting Members |

| Port of Los Angeles Port of Long Beach Dry cargo vessel carriers Tank ship operators Marine oil terminal operators Tug or tank barge operators Scheduled passenger ferry or excursion operators Harbor pilots POLA Harbor pilots POLB Mooring masters Vessel operations labor organization Commercial fishing Recreational boaters (2) nonprofit marine environmental organizations California Coastal Commission |

US Coast Guard Captain of the Port US Army Corps of Engineers US Navy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

Generally, one representative serves on the HSC for each of these groups except as noted. The HSCs operate as public agencies, subject to the “sunshine meeting” Ralph M. Brown Act, and the public is welcome to attend and participate in its proceedings.

The Role of the Marine Exchange of Southern California in Port Safety

Acknowledging its area-wide purview, the LA-LB HSC is administered by an area-wide non-profit organization, the Marine Exchange of Southern California (MXSoCal). As noted in Issue 12 of this series, the MXSoCal includes the Vessel Traffic Service for the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. It tracks all vessels in the region by radar and automated identification system (AIS). It also collects data daily and creates reports on ship activities not only for the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles but also for the oil terminal at El Segundo and the Ports of Hueneme and San Diego. The 99-year-old MXSoCal has been the source of much of the information on ship activities that the nation has learned over the past 2+ years as containerships have brought vast volumes of freight and congestion to the waters of Southern California, the busiest cargo ports in the US.

Additionally, the MXSoCal is the secretariat for the LA-LB HSC, managing the meetings, agendas, and reporting on activities to its board for more than 20 years. The Executive Director of the Marine Exchange, CAPT J. Kipling Louttit, USCG (ret.), also serves as the Executive Director of the LA-LB HSC, aided by his staff at the MXSoCal. For the past 20 years, the Chair of the HSC has been CAPT John Strong, Vice President of Jacobsen Pilot Service, the harbor pilots for the Port of Long Beach. This summer, CAPT Strong handed his duties over to his colleague CAPT John Betz of the Port of Los Angeles Harbor Pilots. Thus, the Harbor Safety Committee has, for more than two decades, presided over and created both collaboration and a set of rules for all mariners using our two busy harbors. Its work may not be well known outside the ports, but the HSC is critical to helping goods and people move safely through our busy harbors.

References

[1] P.L. 107-295, §70103 (b). Area Maritime Transportation Security Plans.

[2] 33 CFR §103.300. Area Maritime Security (AMS) Committee.

[3] US Coast Guard. N.d. National Pollution Funds Center: Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA 90) https://www.uscg.mil/Mariners/National-Pollution-Funds-Center/About_NPFC/OPA/

[4] Ibid.

[5] California Government Code (GOV), Title 2, Division 1, Chapter 7. https://www.slc.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/PF2008-PrevPort-Harbor.pdf

[6] California Emergency Services Act. Article 3.5 Oil Spills. https://law.justia.com/codes/california/2018/code-gov/title-2/division-1/chapter-7/.

[7] GOV §8670.23.1(a)

[8] California Dept. of Fish and Wildlife. N.d. Harbor Safety: Harbor Safety Committees. https://wildlife.ca.gov/OSPR/Marine-Safety/Harbor-Safety.

[9] GOV §8670.23.1(a)

[10] The section noted refers to the members of an HSC being held immune to liability when adopting regulations for their harbor of responsibility.

[11] Allision (def.). The nautical definition of an allision is “the running of one ship upon another ship that is stationary.” https://naylorlaw.com/blog/allision/

[12] Cal. Code Regs. Tit. 14, § 800.6 – Harbor Safety Committee Membership