Baby, Can I Change My Mind?

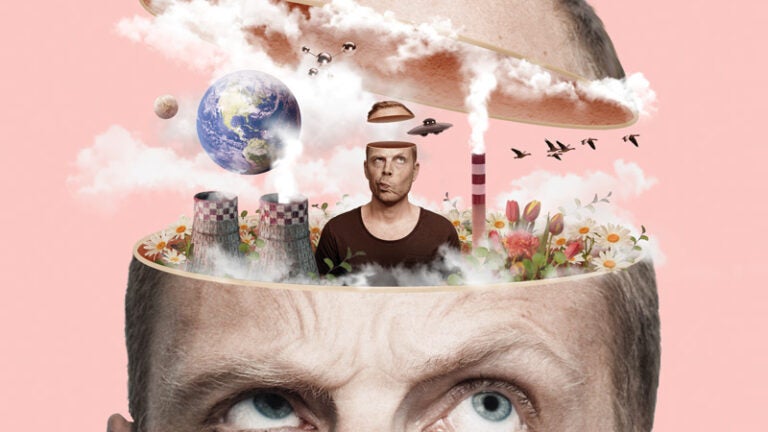

They say seeing is believing. But it would be more accurate to say believing is seeing.

Our beliefs not only define which political party we vote for, what god we worship and who we associate with, they determine which facts we choose to accept or deny.

Once beliefs, no matter how wacky, become part of our identity, they are hard-wired into our brains and almost impervious to contradictory information — and indistinguishable from objective facts.

“What we think of as facts are beliefs that we have decided are true,” said Norbert Schwarz, Provost Professor of Psychology and Marketing at USC Dornsife.

Their power has been reinforced by thousands of years of evolution in which like-minded groups have thrived because they’ve unified through shared beliefs. We’ve been conditioned to reject, or at least view with great suspicion, those who are not part of our clan, those who look or speak differently — or who hold different beliefs.

“The whole species has thrived on being tribal,” said Morteza Dehghani, assistant professor of psychology and computer science at USC Dornsife.

But something has changed. It wasn’t long ago that we believed a common set of facts: The Earth is round, vaccines prevent deadly illnesses and scientists are to be believed when they almost universally agree on a topic, as is the case with man-made climate change.

But today, even the most settled facts are being challenged by people who have formed tribes defined by increasingly outlandish beliefs.

In February, a producer with a Los Angeles-based news outlet contacted USC Dornsife to ask if there was a scholar who would appear on a program to debate whether the Earth was flat. The ancient Greeks firmly established that the Earth is round, yet thanks to the growth of evermore fabulist ideas, there is a small but growing niche who believe that we live on a large, circular plane. The invitation was politely declined based on the principle that there is nothing to debate.

To the flat-Earthers one can add a growing number of oddball beliefs and conspiracy theories, such as QAnon, the Marvel-esque notion that the military convinced Donald Trump to run for president so he could vanquish the forces of evil.

Though humans have always been tribal, a newly emerged force has accelerated the splintering of society: the internet and its spawn social media. Whereas people with bizarre beliefs were largely isolated prior to the internet revolution, today they can easily find like-minded believers online to reinforce their worldview.

“I think social networks have shown to be more divisive than anything else,” said Dehghani. “It’s a propensity that we have as humans that we like connecting with others who are similar to us. Most of the time it’s in terms of values: political orientation, religion. Essentially what the social media sites are doing, they’re just fueling these propensities, whether they’re innate or learned.”

“What we think of as facts are beliefs that we have decided are true,” said Norbert Schwarz, Provost Professor of Psychology and Marketing at USC Dornsife.Searching for Answers

At USC Dornsife, scholars are delving into how we form our beliefs and how, through that knowledge, we might be able to return to a common set of facts — and avoid spiraling into a world of fantasy.

What researchers already know is that it’s very difficult to change beliefs.

“It is just exceedingly rare to ever witness anyone change their mind about some of these important things,” said Jonas Kaplan, assistant professor (research) of psychology at the USC Dornsife Brain and Creativity Institute. “It seems so important for us to be able to change our minds, especially about important topics like climate change or whether vaccines are healthy for us. It can be a life and death issue in that kind of a circumstance.”

Kaplan combines behavior studies with sophisticated measurements of brain activity to understand what makes us tick. His work made headlines in late 2016 when he published a study indicating that people were particularly resistant to political arguments that challenged their beliefs.

Not long after the study was published, a man contacted him with a story that illustrated the peril of rejecting your tribe’s political beliefs and one of the reasons we cling to them so fiercely. The man had worked in the administrations of Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush before going to work for a conservative think tank, but his beliefs began to change until he morphed into a card-carrying liberal.

“The cost of this change for this man was tremendous,” Kaplan said. “When he started questioning the conservative politics, his coworkers were unhappy with this … and he lost his job, ultimately.”

It turns out the reason we defend our most cherished beliefs has to do with why we don’t like to eat garbage.

Our brains are designed to protect not only our physical but our psychological well-being. “If a belief becomes part of our psychological self, it then benefits from all the brain’s protection mechanisms,” Kaplan said.

And the portion of the brain that keeps up this vigil, the insula, is the same one that’s responsible for our gut feelings and emotions, such as disgust.

“It literally is the same part of the brain that says you don’t eat that rotten food,” Kaplan said.

The Imperfect Brain

Knowing how valuable yet difficult it is for almost anyone to remain open to facts that challenge their beliefs, the question becomes how we can short-circuit our brain’s predilection for raising the mental drawbridge when we are confronted with disagreeable facts. Kaplan suggests developing the habit of being aware of how you feel when confronted with uncomfortable information. He also suggests retaining a healthy dose of skepticism, without taking it so far that you become a conspiracy theorist.

The next question is how we interact with people who don’t share our beliefs — but who we wish did.

Schwarz, who has conducted extensive laboratory and field experiments on how people process information, said there is nothing to be gained by trying to argue someone out of their beliefs. In fact, it can be counterproductive.

For example, if you get into an argument with someone at a party about the disproven link between vaccines and autism, your chances of winning the debate are next to zero, but just by raising the issue you inadvertently raise questions about it in those who overhear your debate.

“You should not only worry about the person who holds the wrong belief, but you should also always worry about the bystanders,” Schwarz said.

Kaplan says the key is to connect with people on a social level before tackling contentious differences of opinion. “We know from a lot of experiments that a full-frontal assault is unlikely to work because what you do is you arouse the defenses,” he said.

Schwarz notes that most people are lousy listeners, which is one of the ways that disproved beliefs get lodged in our psyche like a lifelong virus. “We’re very bad at tracking who says what when, where you heard it, and we’re mostly relying on a feeling of familiarity to gauge how widely shared an opinion is,” he said.

And because most of us are less than perfect listeners with clunky memories, we’re also bad at replacing nonsense with fact — even when we have accepted the fact. Schwarz has conducted experiments in which people have accepted a certain truth after first hearing a falsehood. On day one, they’ve changed their mind. But by day three, they’re back to believing the falsehood.

“When you hear (the falsehood) again … it now feels very familiar and it feels like there’s something to it because you seem to have heard it before,” Schwarz explained.

Change for the Better

Despite our brain’s tenacious ability to protect our beliefs — even those that are grounded in hogwash — we are capable, at least over the long run, of changing our minds. Most of the country did so when it came to cigarettes, same-sex marriage and racism, the recent rise in hate speech and crimes notwithstanding.

“It’s not that people never change their minds,” Schwarz said, “but it does require that it seems very important to some, that they’re highly motivated, that they encounter the other arguments very often. That’s one pathway in which things change.”

But for some, there is another way to let go of those familiar, comfortable — and inconveniently false — beliefs, one that perhaps strikes a little closer to the ego.

“The other pathway is what you could think of as social climate changes: that it becomes increasingly difficult to hold some positions — that you’re getting increasingly worried that you look foolish. When social reality changes, beliefs follow.”

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Spring/Summer 2019 issue >>