Pioneering sociologist merged medical sociology and race relations before it was common practice

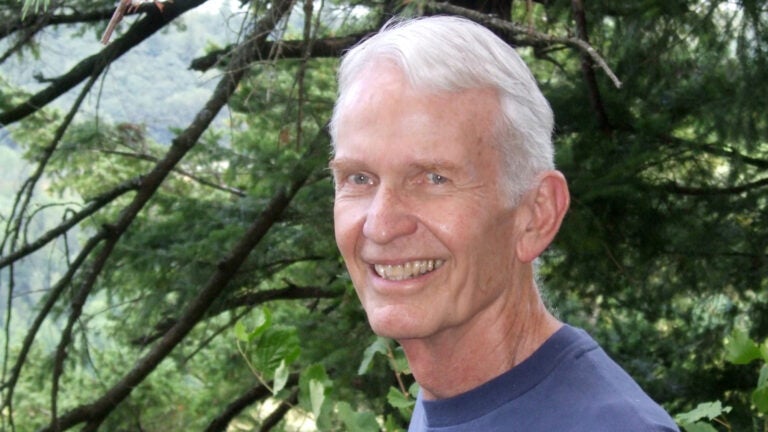

Professor Emeritus of Sociology H. Edward Ransford brought a calm professionalism to his scholarly work, influenced by his two favorite hobbies of playing stand-up bass and riding waves.

“For decades, we in the sociology department benefited from Ed’s calm demeanor; he was a Southern California surfer and a jazz musician,” says Professor Emeritus of Sociology Michael Messner. “Above all, Ed was devoted to undergraduates. During, and after, his many years as the department’s director of undergraduate studies, Ed’s office door was always open to students, and his classes inspired generations of young people.”

Ransford, a pioneering researcher, merged medical sociology and race relations before it became a common practice. He was with the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences since 1969 and taught thousands of students over his tenure.

He died July 24 at 86.

Growing up curious

Ransford was born in 1936 in Pasadena, California, where his father was a marketing and advertising manager and his mother was an artist, producing pottery in a home studio. His father, hailing from Georgia, built a southern-style house in the neighborhood complete with decorative columns.

As a teen, Ransford learned to surf and also gained an interest in music. He and a friend built a radio station in Ransford’s backyard, dubbing themselves “KER” and broadcasting to the neighborhood. Surfing and playing the upright bass became life-long hobbies.

Ransford was part of a cohort of children bussed to schools outside their district, an effort to integrate schools that predated the official end of school segregation in Los Angeles County in 1976. This experience sparked curiosity about America’s complex systems of discrimination and segregation, and later shaped his sociology research.

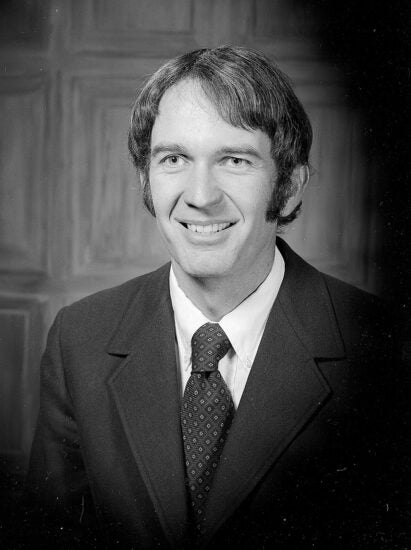

He received a bachelor’s degree in sociology from Occidental College in 1958 and then a master’s degree in sociology from UCLA.

On Aug. 11, 1965, California Highway Patrol officers pulled Black motorist Marquette Frye over for drunk driving in South L.A. The incident turned violent after a scuffle broke out between officers and bystanders, leading to accusations of police brutality. Protests, rioting and unrest, fueled by Black Angelenos’ long-standing frustration at inequality in the city, shook Los Angeles for nearly a week.

Moved by the uprising, Ransford, then completing his sociology PhD at UCLA, embarked on research into the motivations of those who participated. Prior research had found that broader causes such as housing segregation and poverty were underlying reasons for expressions of violent outrage. Ransford probed for more personal reasons, with his research concluding that feelings of isolation and powerlessness were also important drivers for violence.

This work eventually became his doctoral dissertation, a paper published in the American Journal of Sociology, and is still cited today by experts looking back at the incident.

After receiving his PhD in 1968, Ransford taught at California State University, Fullerton until he moved to USC Dornsife in 1969. Over the course of his career, he fused medical sociology with his research into race relations. In 1977, he published Race and Class in American Society. In 1980, he published Social Stratification: A Multiple Hierarchy Approach. His most recent research focused on identifying the barriers to health care among Latino immigrants in Los Angeles.

Service and guidance

Across nearly four decades at USC Dornsife, he taught popular classes to undergraduates and advised graduate students on their PhDs, with the sociology department often turning to him for help with those who were struggling.

“He supervised many over the years, including a few who, due to health or other difficulties, were having trouble finishing. Ed shepherded several such students to completion,” says Messner.

Ransford also served as director of undergraduate studies in the department for nearly 20 years and participated in numerous department committees. Although he retired in 2012, he returned regularly over the years to teach his popular classes on medical sociology and race relations.

Ransford lent a hand in less formal ways, as well. For instance, when Messner first arrived at USC Dornsife, he struggled to figure out the right wardrobe approach that was scholarly without being stuffy. After a few failed tries, Professor Emerita of Sociology Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo suggested he look to Ransford’s relaxed, yet professional style for inspiration. It did the trick, says Messner.

Ransford raised two children, Todd and Jeff, with his first wife Lynn Todd remembers him as a devoted father and excellent role model who taught him how to ride a bike, swim and throw a football with a proper spiral. He insisted on having his dad continue to read to him long past the time Todd could read on his own, just because he liked the sound of his voice.

“Later, when I became a father myself, I developed a new appreciation for all he had done because much of the time I could just do what felt natural and that was the right thing to do,” says Todd.

Ransford met his second wife, Christine Fredericks, while at USC Dornsife. Fredericks, then the director of undeclared advisement for the College, first met Ransford when she sent students his way for advising help. When they both found themselves divorced in the 1990s, they began dating and eventually married in 2000.

“Ed was the best thing that ever happened to me,” says Fredericks, who recalls his kindness as well as his humble nature. For instance, Ransford had won numerous teaching awards over the years at USC Dornsife but never put them on display. “I was always telling him to get them framed, but he never did. Not because he wasn’t proud, but because he just never wanted to toot his own horn,” she says.

Ransford was riding waves well into his golden years, and played bass regularly in the bands Jazz Mandala and The Americana Cats in Carpinteria, where he moved after retirement.

“Ed always seemed so relaxed. He floated gently through the department, like a California surfer boy, waiting patiently for just the right wave,” says Messner. “Watching Ed move, I saw him as a good lesson for all of us in academia, during this era of frantic work speed-up. Ed was never in a hurry, yet he was always getting somewhere.”

Ransford is survived by his wife Christine Fredericks, sons Todd and Jeff, four grandchildren and one great grandchild.