Los Angeles: Birthplace of the Future

The first time David Ulin visited Los Angeles in the late ’80s, he stayed with a friend who had a giant, aerial map of the city pinned to his breakfast room wall.

“What was amazing about it was that every piece of that grid, from the mountains to the sea, was filled in,” Ulin recalls. “And my first thought was, ‘Trantor. It looks like Trantor.’”

Ulin, formerly the Los Angeles Times book critic and now associate professor of the practice of English at USC Dornsife, is referring to the fictional urbanized planet — an entire planet as city — described by science fiction “Grand Master” Isaac Asimov in his acclaimed Foundation series.

It was, Ulin still feels more than 30 years later, a fitting comparison to make with L.A. and its majestic urban sprawl — “the city that ate the desert,” as the celebrated author and urban theorist Mike Davis so memorably characterized it.

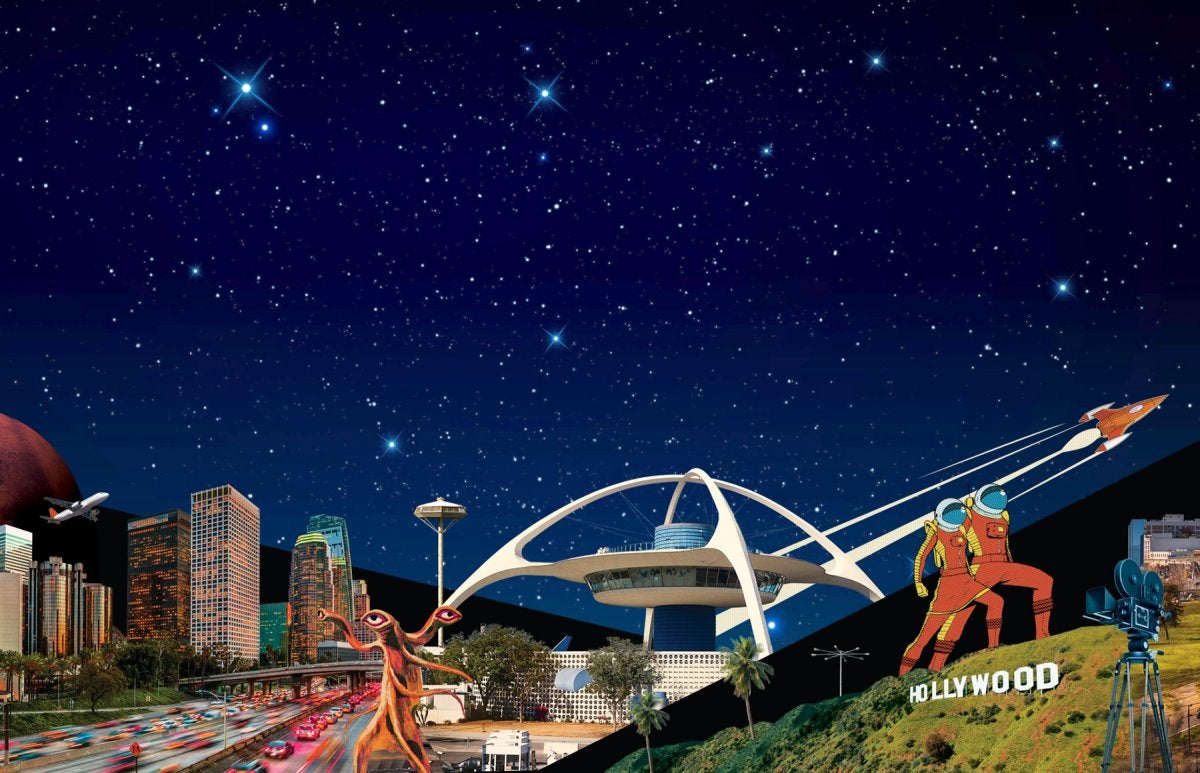

With what once seemed like limitless space to expand, L.A. has long bucked the rules, flouting the established conventions of what traditionalists thought a city “should” be, to set its own radical urban trajectory. While L.A.’s experimental architecture by pioneering practitioners such as Richard Neutra and Rudolph Schindler invented new ways of indoor-outdoor living, and its space-themed designs (the LAX Theme Building and John Lautner’s Chemosphere immediately spring to mind) reinforced its futuristic image, the city’s legendary love affair with the automobile was also carving its legacy into an urban landscape crisscrossed by freeways and embellished with swooping interchanges. When one also takes into account L.A.’s dynamic relationship with the aerospace industry and, thanks to Hollywood, its global reputation as the world’s dream factory, it’s hardly surprising that the metropolis — perched on the western edge of the New World — has long captivated the global imagination as the futuristic city par excellence.

Professor of History William Deverell points out the irony here — that L.A. has been a city of the future for so long that there’s now a past to the notion that L.A. is the future.

Indeed, L.A.’s Chief Design Officer Christopher Hawthorne, professor of the practice of English at USC Dornsife and former architecture critic for the Los Angeles Times, traces the concept of L.A. as a futuristic city all the way back to the 19th century and its history as a place made by successive waves of newcomers.

“If you have a populace who arrived here with the idea that they could remake themselves in L.A., it’s probably only a matter of time before the city begins to think of itself as capable of the same kind of reinvention,” he notes.

Now L.A. faces new challenges to reinvent itself in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, which has hit the city hard, particularly in economic terms. Fewer than half the residents of L.A. County were employed as of mid-April, according to a survey by the USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research.

Sci-Fi City

If L.A. has always been a magnet for those wishing to reinvent a new future for themselves, the city also drew others interested in creating a different kind of futuristic fantasy: science fiction. While L.A. may not have been the birthplace of science fiction, it’s certainly the capital of the genre — the place where sci-fi was embraced and popularized.

“What’s interesting is that we use the future to comment on the present in L.A. in a way I don’t know of other cities doing.”Since the early 1930s — when members of the legendary Los Angeles Science Fiction League, (now the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society), including a teenage Ray Bradbury, met downtown at Clifton’s Cafeteria — L.A. has provided a conducive environment for practitioners of the genre. Many, including Philip K. Dick, Robert Heinlein and Octavia Butler, made their mark in a city that allowed them to free their creative spirit.

“Hollywood’s embrace of popular storytelling meant there were financial and creative opportunities for sci-fi writers in L.A. that just didn’t exist elsewhere,” Ulin notes.

The presence of the aerospace industry and the prevalence of space science in L.A., he says, also had a profound influence in both transforming L.A. into an epicenter for science fiction and contributing to its glittering reputation as the city of the future.

But Ulin goes a step further, arguing that L.A.’s setting and infrastructure make it a science fiction city — not just in books and films, but also in reality.

“The dependency on technological intervention to make the city livable in an inhospitable climate is in a lot of ways not dissimilar to what we imagine would happen if we built a colony on Mars,” Ulin says. “And then in the ’50s, all those dystopian invasion-of-Mars movies took place in L.A. because they were shot here.” These two elements, he argues, led to the conflation in the public imagination of L.A. and a futuristic, science fiction city.

Paradoxically for a city built and promoted by its boosters as a utopian paradise, the overwhelming majority of the sci-fi written, filmed and set in L.A. has been — like those alien invasion movies — distinctly dystopian. Davis’ 1998 book, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster, tallies the novels and movies featuring L.A.’s destruction: at least 138 from 1909 to 1999, something in which, Davis claims, the city takes a certain civic pride.

Even when L.A. isn’t being annihilated by aliens, other dystopian visions of the city abound, from Steve Erickson’s early novels, Rubicon Beach and Days Between Stations, which are set in a dysfunctional, broken down, futuristic L.A., to Cynthia Kadohata’s In the Heart of the Valley of Love, which takes place in L.A. in the 2040s, where everything, Ulin says, “is just bigger and kind of worse.”

L.A.’s most iconic dystopian fantasy remains, of course, the acid rain-washed hellscape of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, a film inspired by Philip K. Dick’s award-winning novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? One of the film’s key settings, the 19th-century Bradbury Building in downtown L.A., is a physical manifestation of just how intimately science fiction and reality can be interwoven in the City of Angels. The Bradbury’s distinctive, wrought-iron railings and open-cage elevators provided an unforgettable backdrop for much of Scott’s film, but the building’s design was actually inspired by another work of science fiction — America’s earliest, in fact: Edward Bellamy’s 1887 novel, Looking Backwards, which takes place in 2000, 19 years before Blade Runner is set but 18 years after it hit our screens in 1982.

“What’s interesting,” Ulin says, “is that we use the future to comment on the present in L.A., in a way that I don’t know of other cities doing.” The further we move away from 1982, the more Blade Runner looks like a film about how Angelenos viewed their downtown at the time as a scary wasteland, he argues, and not a movie about 2019, when it’s set.

“I think that’s often what science fiction does,” Ulin says. “We think about science fiction as an imaginary excursion into the future, but really it’s a projection of the present.”

A Better Tomorrow

Now that we’ve caught up with Scott’s sci-fi masterpiece, what’s fascinating, Ulin notes, is that in 2020 we don’t live in the L.A. of Blade Runner. Instead, he says, we live more in the L.A. of In the Heart of the Valley of Love, a city in which the wealthy live in gated communities while everybody else must make do outside them.

Hawthorne, one of the nation’s foremost experts on the built environment, is determined to change that. As L.A. turns its back on the dystopian fates so often predicted for it in science fiction and instead reinvents and redefines itself for the 21st century and beyond, he’s working to find more user-friendly, sustainable and equitable solutions to the city’s multiple challenges.

“We’ve always toyed with both utopian and dystopian ideas of what our future would be,” he says, “and L.A. was always capable of standing in for the future city in either scenario.”

However, Hawthorne argues that this is a strength. “L.A. has been seen for most of its modern existence as unfinished, in eternal flux or on its way to some dystopian or utopian future, far more than New York, Chicago or San Francisco. Our ideas of what those cities mean and what they look like are much more fixed and immovable.”

For a long time, L.A. always assumed it had more room to grow, more space to conquer. “Being aware of our limits now that we’ve run out of room to expand has produced a shift in mindset in terms of how we see the future,” Hawthorne says.

“We’re moving to a city that will not be so reliant on the car or the kind of low-density sprawling development that has marked so much of the region.”

Those two building blocks, how we live and how we get around, are undergoing dramatic reinvention as L.A. moves toward a future that actually looks a lot more like its past — a city with a bustling downtown, that’s more connected, that has more affordable housing, more successful public open spaces and a mature and comprehensive transit system.

“That’s what the future of L.A. looks like and that’s how the voters have told us they want the future of the city to look,” Hawthorne says.

Is there a certain irony in the fact that L.A. is now looking to its past to become a city of the future?

Deverell, the historian, thinks not.

“L.A. embraced and greatly contributed to the jet age aesthetic.”“I always think we should look to the past to figure things out,” he says. “The past is not way behind us. It’s right at our shoulder; it’s right there. It’s how we understand better the present and to understand the present is to make steps in the right direction for the future.”

As he draws a blueprint for our urban future, Hawthorne is also helping USC Dornsife build bridges between its experts and community leaders through his 3rd LA project, which he brought to USC in January. This laboratory for urban reinvention will be a cornerstone of USC Dornsife’s Academy in the Public Square initiative, which encourages USC Dornsife scholars to collaborate with policymakers and nonprofit and industry leaders to address complex challenges such as climate change, affordable housing and public health.

“USC Dornsife has embraced that set of challenges and really sees itself as a proving ground for new ideas, new technologies, new solutions for helping build this more equitable, and, in some ways, more resourceful city of the future,” Hawthorne says. “We hope that the Academy in the Public Square will play an important role as a convener for these conversations. There’s more momentum, I think, at USC than in any other institution in the region to galvanize work on those fronts.”

Even as L.A. evolves, Hawthorne believes the city will remain a futuristic icon in the world’s imagination.

“I think because of Hollywood and the creative industries that are here, this will always be a center for innovation.”

Deverell agrees.

“If you’re a city of the future, then that’s built on optimism,” he says. “I would like to be part of that. Who wouldn’t?”

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Spring/Summer 2020 issue >>