Food insecurity in LA County remains well above national average, despite slight decline

Key points:

USC Dornsife researchers found that in October 2024, 1 in 4 L.A. County households — about 832,000 — experienced food insecurity. Among low-income residents, the rate is 41%.

While the rate of food insecure households has dropped to 25% — a 5% decline from 2023 — it’s still well above pre-pandemic levels and the national average of 14%.

The number of Angelenos who experienced nutrition insecurity in 2024 was even higher, at 29% of households lacking nutritious food options.

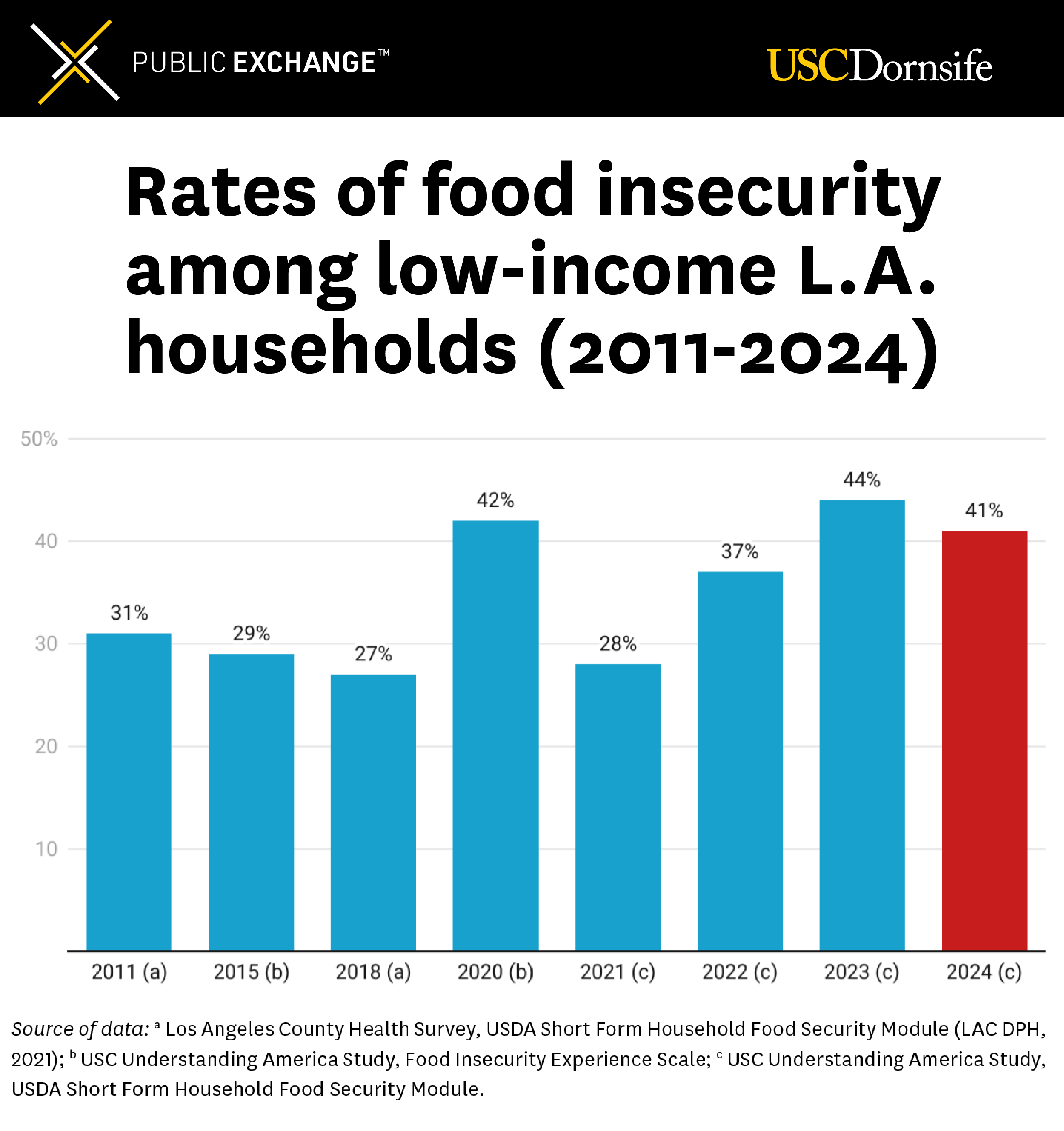

Despite a modest 5% improvement since 2023, food insecurity in L.A. County remains alarmingly high — well above the national average and L.A.’s pre-pandemic level. A USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences study found that as of October 2024, 25% of L.A. County households — about 832,000 — struggle with food insecurity. By comparison, the national average is just 14%. Among low-income households in L.A. County, 41% experienced food insecurity in 2024, compared to 27% pre-pandemic.

“The high cost of living and food, coupled with cuts to assistance programs – persistent challenges for Angelenos – continue to fuel the crisis,” said Kayla de la Haye, lead author of the study and director of the Institute for Food System Equity at USC Dornsife’s Center for Economic and Social Research.

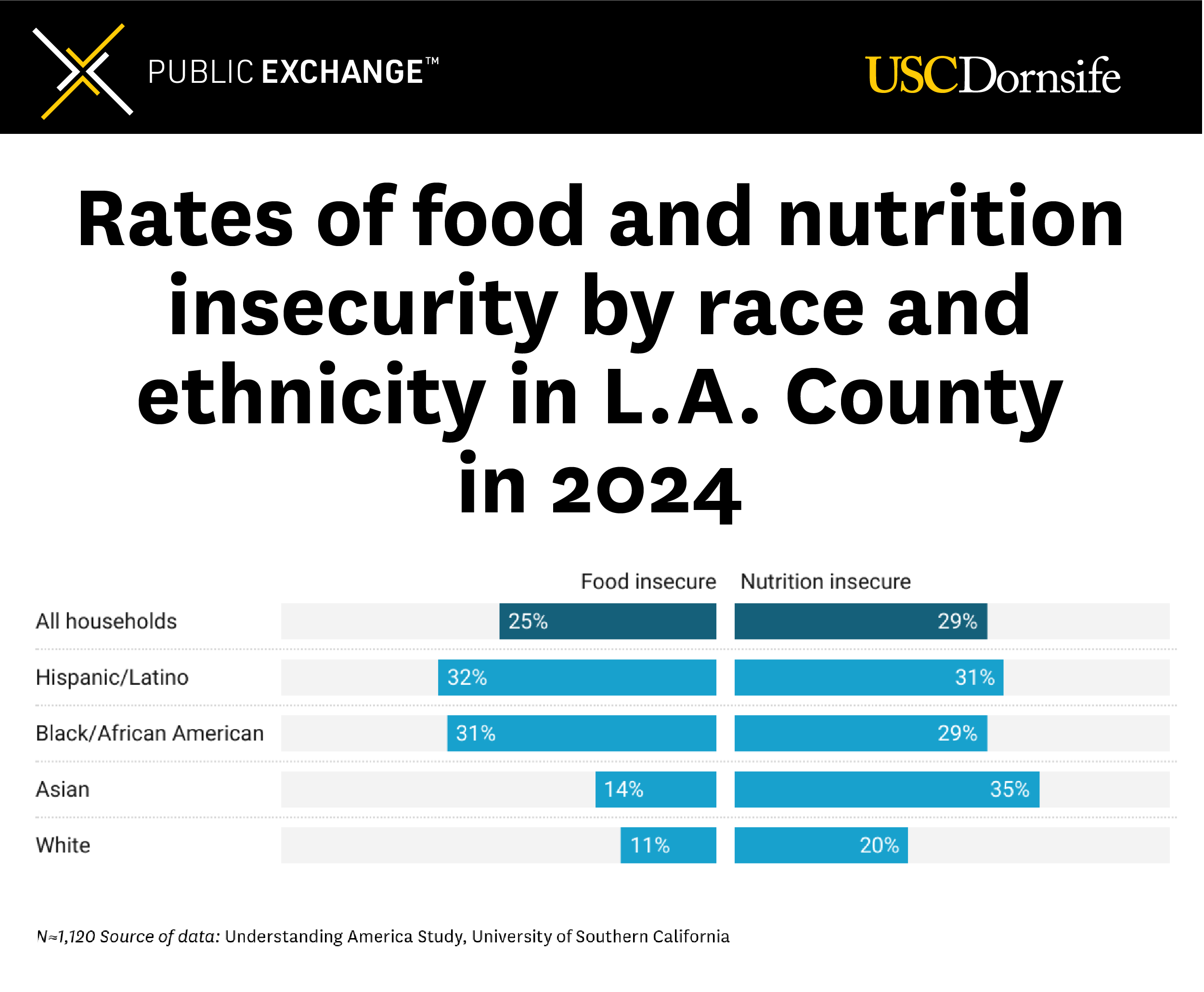

The study, spearheaded by USC Dornsife’s Public Exchange, also highlights relentlessly high rates of nutrition insecurity — characterized by limited access to healthy foods — which affects 29% of residents. Asian communities were disproportionately impacted, experiencing higher rates than other racial and ethnic groups.

Pandemic programs provided relief

During the COVID-19 pandemic, enhanced federal food assistance programs — known as CalFresh in California and SNAP nationwide — and expanded L.A. County food initiatives, helped reduce food insecurity among low-income households to pre-pandemic levels of 28% in 2021. However, the rollback of emergency boosts to these programs in 2022 and 2023, coupled with surging inflation, eroded those gains. By July 2023, food insecurity among low-income households surged to 44% — surpassing the pandemic peak of 42%.

The study also outlined fluctuations in food insecurity among all L.A. County households from 2021 to 2024, underscoring the precarious nature of access to food in the region. These trends are reflected in key data points that illustrate these changing rates and the scope of the crisis over time:

- 17% in December 2021 (553,000 households)

- 24% in July 2022 and December 2022 (802,000 households)

- 30% in July 2023 (1,002,000 households)

- 25% in October 2024 (832,000 households)

“We know that when programs lose funding or are terminated, food insecurity rates rise,” said de la Haye. “The correlation couldn’t be clearer.”

Low-income households hit hardest

This study’s findings align with data from earlier USC Dornsife studies, showing that food insecurity continues to disproportionately affect low-income, Latino, Black and young adult populations. Among low-income households, food insecurity remains very similar to the rate in the first year of the pandemic (42%). Latinos account for 76% of those impacted, with 69% between ages 18 and 40 and 59% women. Just under half (47%) of households with food insecurity have children.

“We’re trending in the right direction, but rates of food insecurity remain unacceptably high, particularly for communities of color and low-income individuals,” said de la Haye. “The evidence is unequivocal: Expanded, fully funded assistance programs and investment in our local food initiatives reduce food insecurity. Now, it’s about translating that evidence into action.”

Stark disparities in nutrition and food insecurity

The study includes findings from the first-ever tracking of nutrition insecurity among adults in L.A. County, covering data collected between 2022 and 2024. The results reveal disparities that extend beyond simply getting enough food. Nutrition insecurity — marked by limited access to healthy, nutritious food — was found to be 4% higher than food insecurity, affecting 27%–29% of Angelenos. Among racial and ethnic groups, Asian residents experienced the highest rate, with 35% affected.

When the researchers compared nutrition insecurity to food insecurity, they discovered significant racial disparities. Food insecurity rates among Black (31%) and Hispanic (32%) individuals are now three times higher than those among white residents (11%). In contrast, only 14% of Asians reported experiencing food insecurity.

“Tackling food insecurity isn’t enough without addressing the disparities in nutrition across racial and ethnic groups,” de la Haye added.

Food assistance programs fall short

Even though high food insecurity rates persist, many of the neediest Angelenos are not participating in food assistance programs. Only 29% of food insecure households in L.A. County are enrolled in CalFresh, and just 9% in WIC, the federal nutrition program for women, infants and children. Yet, among those receiving aid, many still struggle:

- 39% of CalFresh recipients are food insecure; 45% face nutrition insecurity.

- 24% of WIC recipients are food insecure; 47% are nutrition insecure.

Based on their findings, the researchers recommend renewed investments in evidence-based interventions, including:

- Expanding financial support through CalFresh and WIC.

- Making healthy, culturally relevant foods more affordable.

- Increasing funding for food banks and pantries.

- Sustaining local initiatives to strengthen the food system over the long term.

About the food and nutrition insecurity study

The study is based on data from the Understanding America Study (UAS), administered by the USC Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research (CESR), using a representative sample ranging from 1,120 to 1,201 participants.

This work was supported by USC Dornsife’s Public Exchange and by a grant from the National Science Foundation.