Cool Science

At the bottom of the Earth — the planet’s coldest, driest, windiest place — the sky radiates a lavender-yellow hue in the midnight sun.

Whiter than milk, the blanket of ice seems infinite. Amid the Antarctic ice sheets, a mountain rises 6,000 feet near the summit of Mount Terror.

This is Manahan Peak.

“I was in Antarctica and someone said to me, ‘Did you know there was a Manahan who explored Antarctica before you? There’s a mountain called Manahan Peak,’ ” recalled Donal Manahan, professor of biological sciences in USC College.

“I had to tell him, ‘Well, actually that was named after me.’ I’m very humbled by it. It’s really an honor.”

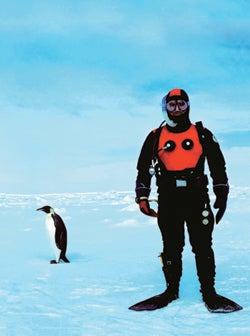

Donal Manahan of USC College poses before diving under the ice during one of his early Antarctic expeditions. Photo by Cornelius Sullivan, courtesy of Donal Manahan and the Daily Trojan.

Manahan Peak is located in a famous part of Antarctica, near where Sir Ernest Shackleton started his trek toward the South Pole during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration at the turn of the 20th century.

But Manahan has added a new dimension to the work of early explorers who roughed the gigantic continent the size of Canada, North America and Central America combined. His is the first formal graduate training program held on the seventh continent that connects young scientists to the last great wilderness.

“I wanted to bring students out of the classrooms, out of the laboratories,” Manahan said, “and take them on expeditions literally to the end of the world.”

In 2000, an international committee named the peak after Manahan for his contributions to research and education on the continent. He has been the chief scientist on more than 20 expeditions.

In 1994, Manahan founded the National Science Foundation-sponsored International Graduate Training Course in Antarctic Marine Biology, the first of its kind.

The month-long course administered through USC College focuses on integrative biology — the study of organisms from their genes to the functioning of the whole organism. Participants are also exposed to an array of Antarctic disciplines: atmospheric sciences, glaciology, chemistry and geology to name a few. Their team-oriented laboratory and field-based projects probe how life adapts in extreme environments.

“When you take people away from their home institutions and home departments, both physically and intellectually, they are much more willing to work together across traditional boundaries,” said Irish-born Manahan, also former director of the USC Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies, housed in the College.

“The concept of teamwork in graduate education is a central aspect of this training program.”

Two students perched at the edge of Ross Island in Cape Evans peer out over a large iceberg trapped in a flat sheet of sea ice. Photo by Scott Applebaum.

To date, more than 200 faculty and students representing 30 nations have participated. Of 400 applicants, 25 graduate students and postdoctoral fellows are chosen to make the journey each summer, a season in Antarctica when the sun never sets. A dozen professors and teaching assistants nationwide lead the scientific expeditions, with Manahan at the helm.

“We know there are vital connections between the largely uninhabitable polar regions and the rest of our planet,” Manahan said. “My hope is that we will raise the awareness of the importance of polar regions for the future of human society.”

Manahan’s own expertise is animal physiology. He explores how animals thrive in extremely cold temperatures. As a new assistant professor at USC, he began his first scientific explorations in Antarctica in the early ’80s.

“What prompted me there in the first place was a simple idea,” Manahan said. “I wanted to study the large, cold biosphere on the Earth’s surface.”

The cold biosphere consists of habitats as chilly as a refrigerator. It is a major environment on Earth, making up approximately 90 percent in volume of the living biosphere (including the deep ocean) above the Earth’s surface.

“That’s what drew me to the cold.”

Group members fish at an ice hole for specimens they will use in physiological studies conducted in the lab. Photo by Scott Applebaum.

He was in Antarctica in the mid-’80s when the ozone hole was first discovered. Atmospheric chemists had presented findings showing a very rapid decline of ozone over the Antarctic. The ozone layer in the upper stratosphere prevents ultraviolet light — which can cause skin cancer and damage plants and animals — from reaching the Earth’s surface.

The depletion was attributed to chorine in the atmosphere, mainly chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) used in aerosols, refrigeration coolants and electronic cleaning solvents. CFCs are mostly released over the United States, Japan, Europe and Russia but journey up into the stratosphere and distribute around the globe.

The worst ozone depletion occurs in Antarctica because its extremely low temperatures cause cloud formation in the relatively dry stratosphere. These polar clouds are composed of ice crystals that provide the surface for a multitude of reactions, many of which speed the degradation of ozone molecules. Fears of ozone reduction in the Northern Hemisphere have restricted the use of CFCs worldwide.

During a lecture he attended in Antarctica, “I was falling off my chair in shock about how big the ozone depletion was and that they had discovered it was driven by human-made CFCs,” Manahan said.

“A week later at USC, I told my undergraduate class, ‘I just returned from Antarctica and want to share this important information with you before the world knows about it,’ ” said Manahan, special adviser to USC College Dean Howard Gillman on enhancing undergraduate studies in natural sciences.

Six months later, the ozone hole had become one of the decade’s biggest news stories.

Now, a different problem has put Antarctica under the international spotlight. Scientists have found that the burning of fossil fuels during the past century has increased concentrations of heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere, preventing heat from escaping to space — somewhat like the glass panels of a greenhouse.

As concentrations of these gases continue to increase in the atmosphere, scientists say, the Earth’s temperature is climbing in a phenomenon known as global warming.

Some regions of Antarctica have warmed sharply in recent years, causing ice shelves to break and accelerating the sliding of glaciers.

In the Arctic, experts say, the warming and loss of ice is a serious threat to polar bears. In Antarctica, the number of Adelie penguins is plummeting in some regions. Scientists warn that many cold-adapted species are at risk of extinction during this century.

“For today’s organisms, we’re trying to figure out who’s going to be able to handle tomorrow’s problems,” Manahan said. “So we’re trying to predict the winners and losers. In Antarctica, we have a natural laboratory where things are changing quickly.”

Scientists warn climate change and the loss of Antarctic ice shelves will result in rising sea levels in other parts of the world.

“Changes there will affect the entire planet,” he said. “People hadn’t before been thinking of global connectivity of the entire planet. The general public was saying, ‘I know things are changing in the North and South Pole, but is that going to really affect me in Los Angeles?’ And the answer is yes.”

David Ginsburg (left), a lecturer in USC College’s Environmental Studies Program, and Robert Ellis, a Ph.D. student at the Plymouth Marine Laboratory in the United Kingdom, examine a starfish in the laboratory at McMurdo Station in Antarctica. Photo by Jimmy Lee.

Near the U.S. Antarctic Program’s central base at McMurdo Station, Manahan and his group oversee the collection of a wide variety of organisms — from microbes to fish.

“We’re looking for universal principles when we study these organisms,” Manahan said. “We hope to answer an important question, ‘Can life on this planet adapt quickly enough to the changes that are being induced by humans?’ ”

For underwater collections, divers carry 100 pounds of gear and plunge into 12-foot tubes of cored ice leading to frigid waters teeming with life. Over the years, Manahan has made such dives himself. Now he lets students enjoy the experience.

David Ginsburg, a lecturer in the College’s Environmental Studies Program, participated in this past season’s Antarctica expedition for the fourth time. On his initial trip as Manahan’s Ph.D. student years ago, he took his first ice dive.

“I was a mess,” Ginsburg recounted. “What was I thinking, a guy born and raised in Los Angeles, jumping into below-freezing water through a shoulder-width hole in the ice?”

Despite his angst, he relished collecting species, and has since experienced many successful dives.

“The most drastic thing you notice when diving in Antarctica is the gigantism,” Ginsburg said. “Giant sponges, invertebrates — starfish the size of basketballs.”

Scott Applebaum had one word after exiting the U.S. Air Force cargo plane from New Zealand on his first trip to Antarctica this year.

“Penguins!”

The postdoctoral researcher in Manahan’s laboratory and his teammates were greeted with a waddle of emperor penguins at the remote ice runway — surprising since penguins rarely stray so far inland.

Applebaum never tired of the Adelie penguins with white rings around their eyes and the taller, bigger emperor penguins with bright yellow-orange patches around their ears. Penguins often waddled by during outdoor research, but the scientists never interacted with them. The Antarctic Treaty protects the flightless birds.

A Weddell seal pokes its head out of an icehole. Photo by Jimmy Lee.

Seals were also a common sight. They sunbathed on slabs of ice and often swam up the long ice holes used by divers and poked their heads out.

Some participants found it difficult to sleep in the perpetual daylight. But even that had its perks. After midnight, the sun was still up and the sky gave off a spectacular glow.

They spent much of their long days in the lab.

Another of Manahan’s teaching assistants was postdoc Jimmy Lee. He recalled visiting the hut where the British explorer Robert Falcon Scott stayed during his famous expeditions, his last ending in his death in 1912.

“It was like stepping back 100 years in time,” Lee said. “It felt like the whole crew just stepped out and would return any minute. There was a toothbrush still in its tin cup.”

In addition, Manahan wants participants to become better versed in the realities of environmental policymaking. At McMurdo Station, they have opportunities to discuss issues with visiting legislators and their senior staff.

“If scientists can’t affect environmental policy, then we’re not going to be able to make a significant difference,” Manahan said. “A big challenge for the next generation of environmental scientists is how well they are able to communicate with policymakers.”

That is crucial as the Earth’s landscape faces a radical transformation.

“The program introduces students to the part of the planet where changes don’t yet directly impact humans,” he said. “But such things are coming our way.”

Read more articles from USC College Magazine’s Spring/Summer 2010 issue.