COVID-related discrimination unduly impacts racial minorities, study shows

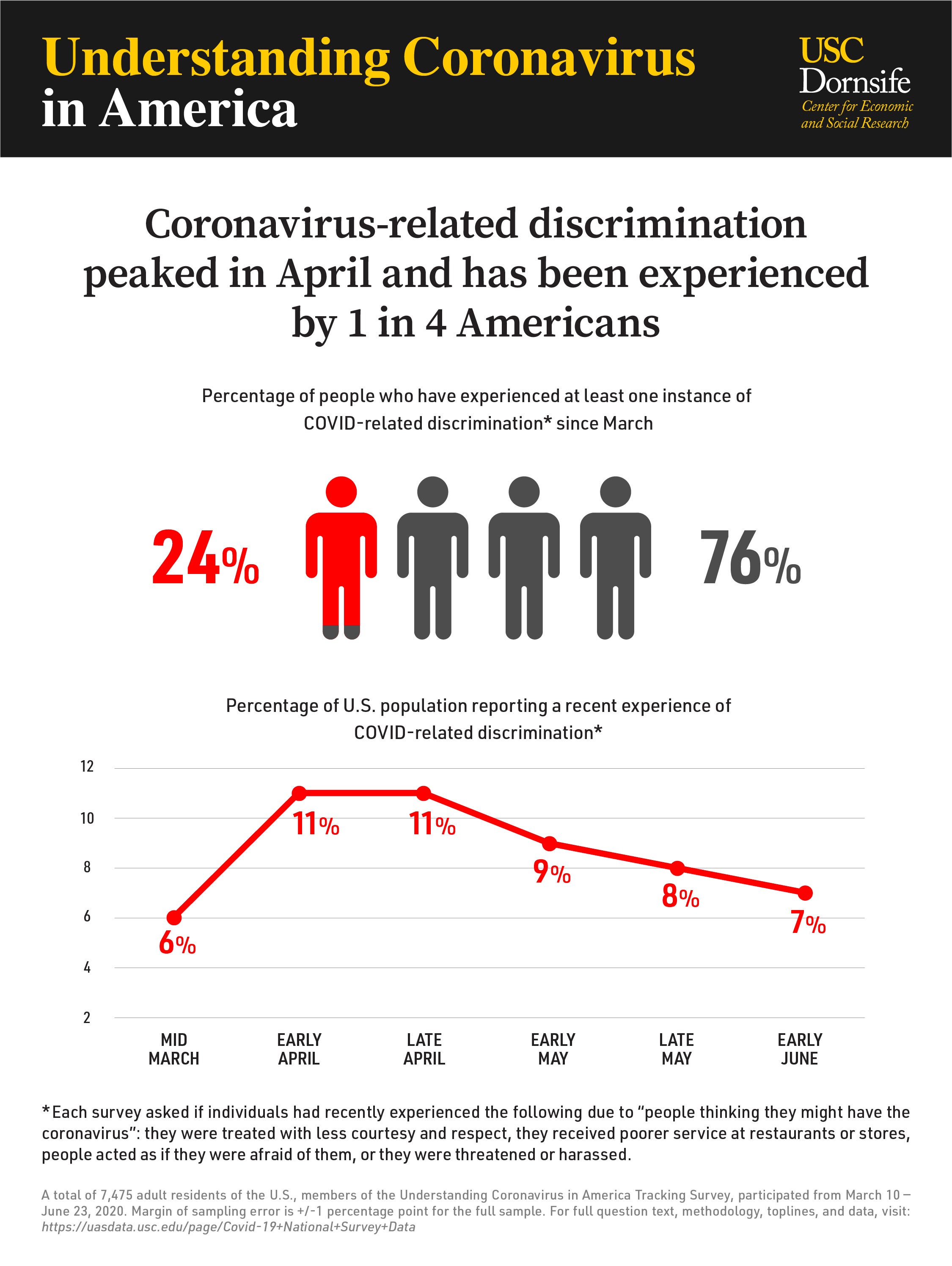

Discrimination by someone who perceives you to be infected with coronavirus is an experience nearly a quarter of all U.S. residents have in common — particularly racial minorities.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, 1 in 3 Black, Asian and Latino people have experienced at least one incident of COVID-related discrimination, compared to 1 in 5 white people, according to the Understanding Coronavirus in America tracking survey conducted by the Center for Economic and Social Research (CESR) at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

The study also determined that the overall percentage of people who experienced a recent incident of COVID-related discrimination peaked in April at 11% and steadily declined to 7% at the beginning of June, though racial disparities persist.

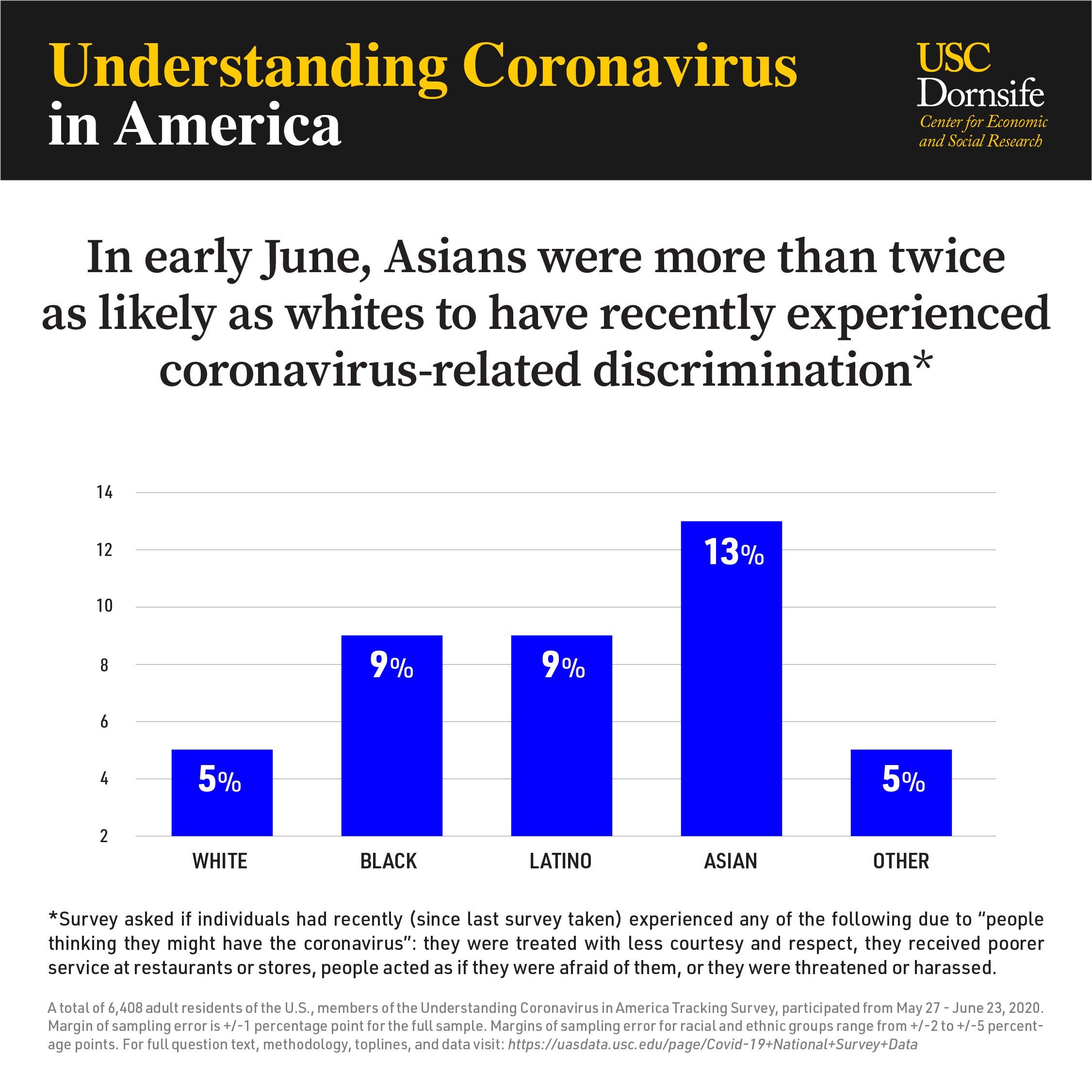

In early June, Asian Americans were more than 2.5 times as likely as whites to experience a recent incident of COVID-related discrimination. Blacks and Latinos were nearly twice as likely.

The prevalence of discrimination also varies by age. Adults between the ages of 18 and 34 were three times as likely as seniors 65 and older to report a recent incident of coronavirus-related discrimination.

“The early spike in the percentage of people who experienced COVID-related discrimination was attributable — in part — to discriminatory reactions to the growing number of people wearing masks or face coverings at the early stage of the pandemic,” said Ying Liu, research scientist with CESR.

“Asian Americans were the first racial/ethnic group to experience substantial discrimination, followed by African Americans and Latinos,” she said. “We also found that in some earlier weeks of the pandemic, people who were heavy users of social media were more likely to report an experience of discrimination.”

A long history of blaming Asians for outbreaks

The findings proved unsurprising to Nayan Shah, professor of American studies and ethnicity and history at USC Dornsife.

“Blaming Asian immigrants and Asian Americans for outbreaks of disease has a long history in California and in the United States,” said Shah, author of Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown (University of California Press, 2001). “Every time politicians and people lash out with taunts, vitriol and violence, public health and democracy suffer. The U.S. is racing to have the highest case numbers and deaths in this phase of the pandemic because basic precautions of wearing masks, physical distancing and respecting each other in public is being willfully ignored.“

The Understanding Coronavirus in America Study regularly surveys a panel of more than 7,000 people throughout the country to learn how COVID-19 impacts their attitudes, lives and behaviors. To measure incidents of discrimination, respondents were asked if “people thinking they might have the coronavirus” acted as if they were afraid of them, threatened or harassed them, treated them with less courtesy and respect, or gave them poorer service at restaurants or stores.

Data from the study, supported in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and USC, is updated daily and available to researchers and the public at: covid19pulse.usc.edu.

Social Stigma Declines

As the overall prevalence of coronavirus-related discrimination has declined, so has the social stigma associated with being infected or having been infected.

In early April, about 70% of the country thought people who had COVID-19 were dangerous and nearly 30% thought formerly infected people were dangerous. By early June, the percentage of Americans who considered infected people to be dangerous had dropped to under 30%, while only 5% thought people who’d recovered from the virus were dangerous.

“As growing numbers of people knew family members, friends and coworkers who were infected with COVID-19, we saw a decrease in the stigma associated with the virus,” said Kyla Thomas, associate sociologist at CESR. “We also saw a steep decline in the percentage of people who perceived coronavirus infection as a sign of personal weakness or failure.”

About the Understanding Coronavirus in America Study

A total of 7,475 adult U.S. residents who are members of the Understanding Coronavirus in America Tracking Survey participated from March 10 to June 23, 2020. Margin of sampling error (MOSE) is +/-1 percentage point for the full sample.

Results from early June are based on a sample of 6,408 respondents who participated in wave 6 of the tracking survey, from May 27 to June 23, 2020. MOSE is +/-1 percentage point for the full wave 6 sample. For racial and ethnic groups in the wave 6 sample, MOSE ranges from +/-2 to +/-5 percentage points. For age groups in the wave 6 sample, MOSE ranges from +/-2 to +/-3 percentage points.

The survey questions, topline data and data files, and a press room featuring this release and other information are available at: https://uasdata.usc.edu/page/COVID19+Corona+Virus.