Castle in the Clouds

What if the components of architecture — walls, windows, ceilings and everything in-between — were used to construct the human mind?

How might the physical space integrate the mind’s two perspectives: the logical, analytical, objective left brain and the intuitive, holistic, emotional right brain?

Enter the 20,000-square-foot, three-story Dornsife Neuroscience Pavilion, which opened November 2012. It encompasses the Dornsife Neuroimaging Center and the Brain and Creativity Institute (BCI), with its Joyce J. Cammilleri Hall.

Walk in and your eyes follow the stark white diagonal walls way up to the atrium windows shining down bright sunlight. Immediately, there’s a feeling of something significant happening inside.

To the left — or south — you will find a world-class auditorium designed by Yasuhisa Toyota, the acoustician also responsible for the concert hall portion at Walt Disney Concert Hall and the New World Center, among other top performance spaces around the globe.

This is where musical performances, theatre, poetry readings and lectures take place.

Directly across to the right — or north — are the modern ways of investigating the human brain in operation: a 3-tesla magnetic resonance scanner and a laboratory of electroencephalography (EEG).

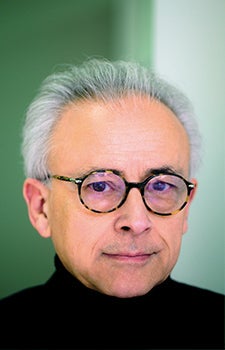

University Professor Antonio Damasio, director of the Brain and Creativity Institute (BCI), created the Dornsife Neuroscience Pavilion so that the scientific ways of investigating the human brain in action is available in a building that includes an amphitheater for concerts, poetry reciting and lectures. Photo by John Livzey.

“So you have these two giant creatures opposite each other — the brain scanning devices on one side,” said University Professor Antonio Damasio, BCI director. “Then on the other, you have the traditional way of investigating human mind and behavior that goes all the way back to the Greeks: an amphitheater where you can hear a human being reciting poetry or playing music or reflecting on the state of humankind in a lecture.

“All of these endeavors are possible under one roof.”

Nirvana of Neuroscience

In recent years, neuroscience at all levels has developed enormously.

In particular, the level of the mind concerned with higher behavior, the higher mind, has been significantly strengthened, Damasio said. “As a result, we have become, for the first time, able to join the world of investigating human behavior and human mind, which has been traditionally carried out through the arts and humanities.”

Arts and sciences speak to one another, he said.

Designed by Yasuhisa Yoyota, also responsible for the Walt Disney Concert Hall, the Joyce J. Cammilleri Hall’s acoustics are peerless. Photo by John Livzey.

“We built it this way to make people go back and forth across these worlds,” said Damasio, David Dornsife Chair in Neuroscience and professor of psychology and neurology, “and to allow students and young investigators to see quite clearly how these worlds naturally interconnect with each other. How the world of, say, theatre or music is not separate from the world of science. And vice versa.”

Damasio and his wife, University Professor Hanna Damasio, BCI codirector, said calling the building the Brain and Creativity Institute brings to the fore the fact that the brain research conducted under its roof is fused with the realm of arts and creation.

The Damasios founded the BCI in 2006. The lead gift for the expanded building came from longtime university supporters Dana Dornsife and USC Trustee David Dornsife. Both sit on the BCI Board of Directors, which David Dornsife chairs. The Los Angeles-based architectural firm Perkins+Will fashioned the new BCI out of space between existing structures.

“Creativity is a very distinctive human ability,” Antonio Damasio said. “Human beings are creative and that’s one feature that makes them special. The idea was to have a building that would manifest very clearly these two strands of inquiry. The one that has to do with science and the traditional one that has to do with philosophy or the arts.”

Musical Brain

One new study taking place at the BCI is connected to the arts. It seeks to understand what happens to the brains of young children learning music using the El Sistema method — sometimes referred to as “passion first, refinement second.” Developed in Venezuela, the method teaches children with few resources to overcome adversity by first strengthening their spirit through music.

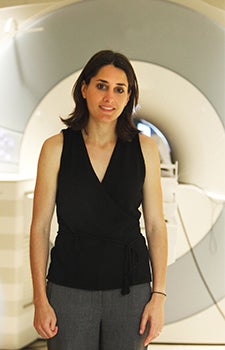

University Professor Hanna Damasio, BCI codirector, also directs the Dana and David Dornsife Cognitive Neuroscience Imaging Center. She has pioneered the use of brain imaging methods in the study of brain lesions, such as computerized tomography and nuclear magnetic resonance imaging, which can be used for diagnosing all diseases that affect the brain. Photo by John Livzey.

Led by Antonio and Hanna Damasio, Dana Dornsife Chair in Neuroscience and professor of psychology and neurology, and neuroscientist Assal Habibi, herself a classical pianist, researchers are following children for five consecutive years from the start of their musical education, using standard psychological assessments and advanced brain imaging to track their brain, emotional and social developments. An expert on musical education from the USC Thornton School of Music, Beatriz Ilari completes the research team, which includes several graduate students of music and neuroscience.

The team is collaborating with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Association and the Heart of Los Angeles (HOLA) on the project that will offer new insights and data about the role of early music engagement in learning and brain function. Study advisers include American cellist and virtuoso Yo-Yo Ma, a member of the BCI board; the renowned conductor and pianist Daniel Barenboim; and USC Thornton’s Midori GotÃ…Â, a USC Distinguished Professor and the Jascha Heifetz Professor of Strings.

“We should not be studying music without musicians,” Antonio Damasio said, “and we treasure the advice we get from these giants of music.”

Clairvoyant Computers?

On the pavilion’s first floor, Jonas Kaplan, research assistant professor of psychology, is among the BCI researchers who use the functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner to study the human mind.

In the past, scientists at the BCI have programmed computers to predict what a person is seeing, hearing or simply touching. They discovered that as you look at an object, your brain not only processes what the object looks like, but remembers what it feels like to touch. A computer examining activity from the part of the brain processing touch could predict the object participants were looking at and holding — a fluffy sponge, a ball of yarn, a light bulb.

“We’re now actually moving beyond just looking at stimuli, hearing and touching things, into the realm of imagination,” Kaplan said.

In the experiments, participants inside the scanner watch silent videos, of say, a rooster crowing.

“They don’t hear anything,” he said. “But when they see the video they have an imaginative experience. They hear the sound of crowing in their mind’s ear going along with the video.”

Or they watch someone playing the piano or a glass shattering or coins falling onto the floor — all with no sound. By analyzing the patterns that are evoked in the auditory parts of the brain, the computer can determine what sound the person was imagining in that circumstance and which video they were watching.

This brings scientists closer to knowing where sight, sound and touch come together or are synthesized in the brain.

Jonas Kaplan, research assistant professor of psychology, is among the BCI researchers who use the functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner to study the human mind. Photo by John Livzey.

“Some parts of the brain appear to integrate sound and touch,” Kaplan said. “And there are other parts that integrate touch and vision. And there may be parts that integrate all three. We want to map out these systems.”

They are also looking at where the sources of imagination are in the brain.

“Using the patterns of activity in those parts of the brain, we were able to determine what people were imagining, which then gives us evidence that this part of the brain is involved in imagining, the contents of imagination.”

The Zen-like feeling of the new pavilion follows the researchers as they walk upstairs. They pass walls where the works of contemporary artists are displayed and dispersed between offices in spaces for interaction or quiet reflection. Most of the offices have open ceilings and glass walls. The openness creates a sense of community and promotes collaboration.

Always, what strikes you most is the brightness from the windows of the atrium, positioned in the center so that the light emanates outward like a star.

“The building is fundamentally designed to support our intellectual endeavors,” said Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, assistant professor of education, psychology and neuroscience. “So as you walk into the building, unlike most traditional office spaces, you experience a confluence of arts and science.”

Immordino-Yang is perfecting her research on human experience to an art form. In one recent cross-cultural study, she shed light on how individuals feel and show emotions.

Still Waters

In extensive studies, Immordino-Yang presented participants with stories about compassion and inspiration inducing, real-world events — such as the story of Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani teenager who was shot in the head and neck while returning home on a schoolbus. The Taliban wanted to punish Yousafzai for being a girl seeking an education. As Immordino-Yang’s team related Yousafzai’s story to each participant, the researchers studied the participants’ natural behavior — for instance, were they waving their hands or unexpressive while discussing Yousafzai’s miraculous recovery and heroic activism?

Immordino-Yang compared those interviews with the neurobiological correlates in the same participants. At the BCI’s fMRI scanner, she recorded their neural activity while they reviewed the same stories. As the participants reacted to the stories while inside the scanner, they indicated their range of feeling, from weak to being emotionally overwhelmed.

She found that the brain activity underlying emotional feelings differed depending on how expressive a person was in the interview, although everyone in the experiment, expressive or not, reported feeling strong emotions.

“The people who were weeping and grabbing tissues and openly expressive did not report that they felt more strongly than the people who were sitting there calmly deliberating on what the story meant to them and how they felt about it,” Immordino-Yang said.

In one study, Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, assistant professor of education, psychology and neuroscience, has found that people learn from their culture how to express their emotions — whether they emphatically use their hands when they speak or remain inexpressive. Photo by Steve Cohn.

“There were also no differences in the magnitude of the signal in the anterior insula — a brain region that’s important for the experience of emotional states or for feeling. There were no differences in the magnitude of the BOLD (blood oxygen level-dependent) signal there.”

However, more expressive people showed a tighter correlation between brain activity in the anterior insula and the strength of the feeling they reported. In other words, individuals’ behavior predicted the way in which their anterior insula supported feelings, even though more expressive people did not report feeling more strongly and did not show bigger neural responses.

When participants said they felt strongly and were also emotional, those two events were moving together to create a more tightly correlated pattern.

Conversely, those who expressed their emotion more calmly but said they felt strongly showed a looser correlation between how they felt and their brain activity in the anterior insula.

“What we think is going on is that people learn from their culture how to experience their own emotions; they learn how to conceptualize their feelings,” Immordino-Yang said. “Expressiveness seems to be shaped by your own culture and by your own biology, acting additively.”

Shaping your behavior over time may indirectly teach you how much attention you should pay to your body’s reaction to know how you feel, she said, and future experiments are set to test this interpretation.

“So if you’re a person like me who’s super Italian-like and waving my arms around and crying and doing all these things — when I want to know, how do I feel about that young woman who fought the Taliban? — I may be more likely to pay attention to my own bodily response,” Immordino-Yang said. “I might think to myself, ‘Well, my heart’s pounding, my throat is dry, so I must be really upset about this.’ ”

“Whereas I think if you’re a person who’s been taught over time not to show a big bodily response then you would be attending to something else in order to decide. When you’re expressive, there are more prominent cues from your body to tell you, ‘Wow, I really am feeling emotional.’ But when you’re less expressive, the cues may be subtler.

“So, your culture appears to shift the way in which your emotions result in body reactions, which in turn may shape how emotions are experienced. Cultural shaping of behavior may actually change the experience of emotions — not the strength of feelings, but potentially the process by which individuals become aware of and evaluate their feelings.”

Spiritual Science

John Monterosso, associate professor of psychology at the BCI, is an expert on decision-making, impulsivity and self-control. He’s interested in this key step in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and other 12-step programs: recognizing a higher power that can give strength.

“If you ask people who overcome addictions in the 12-step approach, if you ask them what they think happened, many feel very sure that personally for them, spirituality was critical,” Monterosso said. “It’s sometimes explicitly religious, but it isn’t always. It is sometimes a very vague sense of spirituality.”

For example, recovering addicts in AA believe in a connection to something larger, or nature, or the circle of life, he said. Social scientists can’t assume they are right; The addicts who say a belief in a higher power helped them recover may be flat wrong.

“But it seems a greater possibility given the amount of time and attention from people who spend their lives thinking about this, that these psychological experiences are important for overcoming the addiction,” he said.

“As you become addicted you lose connection with other things in your world. Everything begins to fall away, relationships suffer. Eventually work suffers. Life becomes more concrete and specific around the substance.”

People in the 12-step community often say that even before their breakdown of connections to larger things, some kind of lacking in their life was the starting point. A feeling of disconnection was often key to their problem.

The recovery process is often considered related to reconnecting, or for the first time connecting, to some kind of spiritual perspective.

“OK, so I’m a psychologist,” Monterosso said. “We want to think about that in psychological terms. What is their experience psychologically? There’s a ton of research, mainly questionnaires, about people’s spirituality. But there’s little so far that can give us a handle on what these spiritual experiences are about emotionally and physiologically.”

Through interviews coupled with tests on the participants’ brains in the BCI’s fMRI scanner, Monterosso hopes to discover how these spiritual experiences shift people’s behaviors.

“How do they go from a place where they’re responding to only immediate gratification to seeing things more globally, or responding to bigger themes, to bigger considerations?”

Still in the planning stages, the study involves Homeless Health Care Los Angeles’ needle exchange program.

Located in the downtown Skid Row area, the program is meant to decrease the number of drug users sharing contaminated syringes. Monterosso is planning with the L.A. organization to test participants who can help shed light on how their behavior and physiology changes when hearing compelling stories that may bring out a feeling of spirituality.

“We’re hoping to get some idea about how complex emotions related to spirituality are relevant in self-control and recovery from addiction.”

BCI researchers use the functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner to study the human mind. Scientists use a 3-tesla magnetic resonance scanner and a laboratory of electroencephalography (EEG). Photo by John Livzey.

Do Me a Kindness

For the past three decades, researchers studying gratitude believed the emotion was a result of two catalysts: 1) a gift was given at great effort by the giver and 2) the gift fulfilled a serious need for the recipient.

Not so, said Glenn Fox, a Ph.D. candidate in neuroscience at the BCI. While gifts that come at great effort and fulfill a serious need are indeed capable of eliciting high levels of gratitude, one or the other is enough, Fox found.

“High effort or high need alone is sufficient for high gratitude.”

In his research, Fox is relying on the USC Shoah Foundation — The Institute for Visual History and Education and its archive of videotaped testimonies of survivors and other witnesses of the Holocaust.

Fox and his team spent hundreds of hours watching and listening to many of the archive’s more than 52,000 testimonials. They collected scenarios in which a survivor receives some sort of gift. A gift of peanuts to a starving survivor allergic to peanuts might elicit mixed feelings. Other gifts — for example when a prisoner whispers “stay left” to someone exiting a train at Auschwitz, saving his life when all those on the right are sent to a gas chamber — would certainly bring out deep gratitude.

In Fox’s study, participants were asked to take the perspective of the survivor and read about his or her personal experiences while connected to a brain scanner. Participants also filled out questionnaires describing their emotions.

“Our preliminary data shows that gifts eliciting near unspeakable gratitude — for example, being given shelter and food when there is a great personal risk to the giver for doing so — activate brain regions associated with happiness, social bonding and joy,” Fox said.

In the preliminary findings, Fox has discovered that a gift drawing the greatest amount of gratitude is one that helps restore the recipient’s dignity. Using real scenarios from the USC Shoah Foundation, the opportunity to speak one’s own language meant a great deal to survivors taken out of their country.

“If they were taken from France to a concentration camp in Austria, for instance, being able to speak French was really a welcome experience,” Fox said, “even though it didn’t necessarily feed them. Just being able to speak in one’s own language was dignity-restoring and the recipients were grateful for it.”

Fox’s studies indicate that gratitude lives at the center of good human conduct and serves as a fulcrum by which people seek to do right by others. When one is the beneficiary of good human conduct, one experiences a concert of positive emotions ranging from relief to elation, Fox said. These emotions can in turn motivate people to expend great sums of energy to reward those near the source of the good conduct, creating, literally, a virtuous cycle.

“There is something very real about the phrase, ‘pay it forward,’ ” Fox said. “Gratitude is a powerful emotion.”

No Smell Wonder

Neuroscience Ph.D. student Kingson Man was inspired by Antonio Damasio’s The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1999) when he read the book as a high school student in New York City. He chose USC Dornsife specifically to work with the Damasios at the BCI.

Man is interested in how the human senses of sound, sight, touch, smell and taste are merged together. The societal impact of his research could benefit people with brain damage, including semantic dementia, which inhibits one’s ability to distinguish the difference among objects.

“They can’t tell the difference between apples or oranges or, say, different tools,” Man said. “They don’t know how to use a wrench versus a screwdriver anymore. They’ve lost that conception and knowledge.”

Man is investigating how conceptual knowledge is organized and how people might be rehabilitated when they’ve lost that capacity.

“I think a promising strategy is to use yet another sense to try to learn new associations,” he said. “So if you’re trying to tell the difference between a wrench and a screwdriver by looking and touching, what could you do? You could try to recruit a third sense. So these are very manual objects.

“Maybe, to be far-fetched, you could paint a different scent onto each tool. Then you learn that the association of strawberries means wrenches, which are for doing a certain thing. If you just smell it, then you can activate it and you can reach that knowledge through a different route.”

Not far-fetched at the BCI. Researchers under its roof know something is happening here. These scientists are beyond teetering at the cusp.

“Intellect and emotions are not separate,” Immordino -Yang said. “They’re completely feeding off one another and integrated to each other. It’s the ideas themselves that are inspirational to me — and the dynamic culture created here of intellectual exchange and debate.”

The researchers are all, individually and collectively, following the light.

Experience an fMRI scan with a USC Dornsife undergraduate with a story and video

Read more articles from USC Dornsife Magazine‘s Spring/Summer 2013 issue