Growing Anti-CRT and Anti-DEI Legislation Reveals the Continued Institutional Racism of Higher Education

Every spring, as college acceptances and rejections hit the email inboxes of hopeful students across the country, the same racist narrative is used to salvage the feelings of disappointment among white students who didn’t get into their first-choice schools. This perpetual fallacy — that affirmative action and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) admissions policies allow undeserving Black students to “steal” spots from deserving white students at the top universities in the country — has never been backed up by data. But it is repeated, and believed, because exclusion of Black people is one of the original tenets of higher education. We may be 200 years removed from emancipation, but whiteness still reigns supreme.

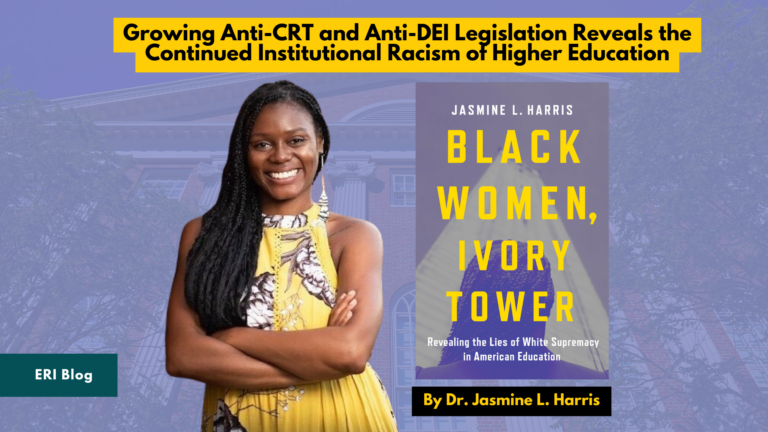

Black students make up less than 7% of the student body at the country‘s most prestigious historically white-serving colleges and universities. It is a number that hasn’t changed much in the last 100 years. In my new book, Black Women, Ivory Tower: Revealing the Lies of White Supremacy in American Education, I examine the history of formalized education in the US and the racism embedded in the creation of this institution. In the process, I had to rethink my own experiences as a Black woman traumatized in educational spaces, and explore the impacts of institutional racism among the Black women in my family.

A majority of predominantly white schools today are also historically white-serving institutions., This dates back to the 1600s with Harvard and other early colleges admitting exclusively white students and persisted to the early years of the civil rights movement in the 1950s. Black people literally built the walls and the floors of university buildings, and there are slave quarters (now repurposed) still standing on these campuses. Yet we remain unwanted in the classrooms. The insidious fear of Black people “darkening” campus communities is a lasting vestige of white supremacy in education. Our learning is seen as something to fear – something to stifle.

Black Diseducation

The systemic distancing of a demographic group from formalized education is called diseducation. When emancipation eliminated laws preventing enslaved Black people from reading and writing, institutions created racialized admissions policies to keep Black people out of prestigious schools. Those anti-literacy laws were established after the Nat Turner Revolt in 1831 amid growing fears of slave insurrection. Post-Reconstruction, Jim Crow established “whites only“ schools to formalize disadvantages in resources and reputation for Black schools. After integration, tracking systems, excessive discipline, and underfunding maintained the spirit of “whites only” education in modern institutions. Following graduation rates among Black people across time without context implies some cultural disinterest in school — but that disinterest has been manufactured via the institutional structures and cultures depressing our success and retention.

School integration was meant to ensure Black students had access to the same educational resources as white students, but the implementation of Brown v. Board of Education closed well-supported black schools and eliminated more than 40,000 Black teachers across the U.S. The effect was to isolate Black kids in schools without protection from the violence of these racialized institutions – directly impacting their academic success. Black soldiers with GI Bills were turned away at the campus gates. Those Black faculty that remain are subject to isolation, surveillance, and discipline designed to minimize our impacts on campus.

Anti-critical race theory (CRT) and anti-DEI legislation are meant to maintain white supremacy and privilege in higher education by rolling back the small progress made on college campuses to improve the experiences and outcomes of Black students in particular. Belief in the necessity of such laws is born of the false narratives of the mediocre Black student being privileged over white students. The irony of fearing privilege while actively benefiting from it is a joke the bill riders are not in on.

Faith and Perseverance

The first manuscript of Black Women, Ivory Tower only had seven chapters, not the eight chapters of the published version. Every interested publisher agreed an eighth chapter was needed, but most thought the new chapter should include some instructions for how to change colleges and universities to be more inclusive. My response was always that Black people shouldn’t be tasked with solving white supremacy. The truth is, I don’t see a way through that isn’t led by the ideas, power, and wealth of white people. As a Black woman, I exist in these spaces, but I don’t control them. I return to them because I believe that my presence affects change, not because I feel welcome there.

Instead, I wrote about faith — my own and that of the Black women across history who face the violence of white supremacy head-on. A combination of spirituality and religiosity, faith in Black communities has been our tool of choice since enslavement began—a necessity for our own survival. I grappled with my own willingness to continue seeking out education and entering educational spaces that I know aren’t meant for me. During the writing process, it read to me like madness. But then again, existing almost entirely on faith can drive one a little mad.

When people ask why we’re still here, why Black people continue attending historically white-serving schools when they clearly don’t want us there, I always come back to my faith. The short answer is that we can’t afford not to be—educationally and professionally, school has value. So, we need to be here. Instead of being forced out we persevere, not just to protest white supremacy, but to prove it can be overcome, in ways however small. We have always persevered. My new book explores the expense of that perseverance. We’re still here – but there is a cost.

Jasmine L. Harris (Ph.D.) is the incoming Department Chair of Africana Studies at Metropolitan State University Denver. She completed her Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota in 2013. Her research examines Black life in predominantly white spaces, including Black students at PWIs, Black DI football and men’s basketball players at universities in the Power Five conferences, and Black sociologists producing knowledge in a white-dominated discipline.

Jasmine L. Harris (Ph.D.) is the incoming Department Chair of Africana Studies at Metropolitan State University Denver. She completed her Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota in 2013. Her research examines Black life in predominantly white spaces, including Black students at PWIs, Black DI football and men’s basketball players at universities in the Power Five conferences, and Black sociologists producing knowledge in a white-dominated discipline.

Dr. Harris has been published in major newspapers across the country, including Newsweek, The Washington Post, the Houston Chronicle, and the Chicago Tribune. In 2021 she was featured in the Vice News documentary College Sports, Inc. Her first book, Black Women, Ivory Tower: Revealing the Lies of White Supremacy in American Education, was published by Broadleaf Books in 2024.