Beyond Resilience: A Call to Action for the Needs of Undocumented Migrants

Three years ago, my state of Connecticut—like many others—issued a stay-at-home order to keep residents safe during the initial surge of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite fear and uncertainty, many enjoyed investing in new hobbies like bread baking or gardening. But the pregnant Latin American migrant women in my community research faced an entirely different reality.

“It was like a trauma,” Jackelín, a 40-year-old woman from Guatemala said. “I didn’t ever want to leave the house. Suddenly, I was afraid of what would happen if I got sick—my children so young, me pregnant. We kept hearing from our neighbors about people losing someone close or about pregnant women dying.”

These women, many of whom were undocumented, lost work in housekeeping and food service. Their partners saw their hours cut or went to work ‘essential’ jobs like landscaping and custodial services, exposing themselves to the novel coronavirus. Despite accounting for just 16% of the US population, Latinxs accounted for 23% of the initial job loss at the start of the pandemic.

Célia, a 35-year-old Ecuadorian, said that her family had her husband undress at the door when returning from his construction job. “Even our toddler panicked, and if his father tried to hug him, he’d yell, ‘No!’”

Even as Célia and her husband struggled with her pregnancy, their reduced income, and fear of contracting COVID-19, Célia focused on planning for their future.

“I talked with my husband about how we could cut back our expenses and ease our stress,” Célia said. “When you have children, you have to be calm for them—not act tense or fight. This is how we seguir adelante [press onward].”

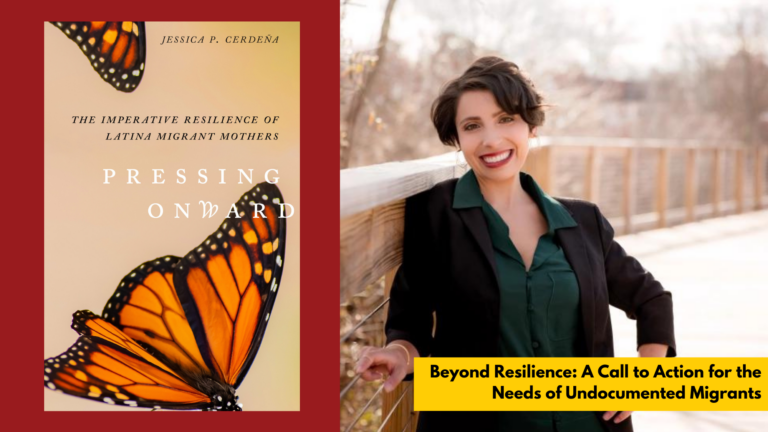

Pressing Onward is the title of my new book, which draws from interviews with 65 women like Jackelín and Célia between 2019 and 2021 to narrate how they overcome adversity to build futures for their children. I observe how these women withstand racism, poverty, and gender-based violence by engaging in spiritual exercises, selecting partners who can help advance their family’s goals, and channeling the wisdom of their mothers and grandmothers. I call this resistance to oppression “imperative resilience.”

When asked about how they deal with stress, many of these women said things like:

Elvira (30, Dominican Republic): “You have to just accept it and adapt, create something nice out of it so you don’t focus on the bad. I don’t throw in the towel easily. I am strong. I endure. I have been through things, and I have overcome them. I try not to think about things because if you dwell on them, you feel sadder.”

Marisol (39, Mexico): “There are times when I get up at dawn and try to pray a lot, to listen to God, so as not to feel anger at everything that has happened to me. I ask for peace and then I become stronger.”

As a clinician-anthropologist, I was stunned by how well these women coped despite all they had been through. I expected them to screen positive for psychiatric conditions, but none of the 65 women I interviewed did. That made me think about what mental health professionals call “resilience,” or positive functioning despite adversity. Most scientists see resilience as something to study so that it can be increased in people who don’t have it. But I argue that resilience is a necessary practice of survival in the face of an uncaring society, and instead call the cognitive and social strategies these women deployed “imperative resilience.”

On asking women what would make their lives better, I heard (1) basic needs, (2) healthcare, and (3) a pathway to legal immigration. When undocumented women and their partners lost work during the pandemic, they could not receive unemployment checks or economic stimulus aid: many turned to risky work painting nails in people’s homes or selling homemade food without proper permits. They relied on mutual aid and food banks to support their children. This should not be the case. We need mechanisms in place to ensure that every U.S. resident can at minimum feed, clothe, and house themselves, whether through universal basic income (e.g., the SUPPORT Act) or the expansion of social support programs (e.g., TANF and SNAP).

Unlike all other Americans, undocumented residents cannot receive healthcare coverage under the Affordable Care Act, which delays necessary care and increases overall costs. Although some places like California, New York City, and, in part, Connecticut, have expanded access to public insurance to many income-eligible residents, regardless of immigration status, we need broader, bolder action to reach the millions of other undocumented people in our country.

Finally, women like Elvira and Marisol, who have lived in the United States for a combined 33 years, deserve a way to claim it as their home. The immigration registry has existed for nearly a century and provides a process for long-term noncitizens to adjust their status, as long as Congress updates the eligibility dates—something it hasn’t done in decades. H.R. 1511, a bill to renew the immigration registry would allow Elvira, Marisol, and an estimated 8.3 million undocumented residents who have lived in the US for extended periods to apply for green cards and live without fear of deportation.

I have learned a lot over the past three years. Most importantly, we need to stop expecting migrants to be resilient; instead, we need to build resilience into our communities so migrants can dream beyond the day-to-day.

About the author:

As a medical anthropologist, Jessica P. Cerdeña is broadly interested in the biosocial underpinnings of health inequities. Her book, Pressing Onward: The Imperative Resilience of Latina Migrant Mothers (order here), centers the ways Latin American migrant women living in Connecticut press onward—or seguir adelante—past traumatic histories, ongoing structural vulnerability, and the COVID-19 pandemic to create opportunities for themselves and for their children. She also examines the impacts of race-based medicine on minoritized patients. She aims to engage her clinical and anthropological training to address health outcomes for marginalized populations.