CAGR Workshop Summary – Knowledge on the Move: Information Networks During and After the Holocaust (April 2022)

Research Workshop co-organized by the Pacific Regional Office of the German Historical Institute Washington (GHI | PRO) and the USC Dornsife Center for Advanced Genocide Research

April 3-5, 2022

Summary by Robin Buller and Anne-Christin Klotz (GHI Washington, Pacific Office Berkeley)

This workshop was conceived with an interest in exploring migrant knowledge as a lens with which to understand the Holocaust. While victims of the Holocaust are not migrants in a traditional sense, they were often in transit, displaced, and crossing boundaries of various forms, be they physical, territorial, or related to power structures. Knowledge was exceedingly important to the Holocaust’s unfolding. The pathways by which perpetrators were able to inflict violence, the choices that bystanders made when deciding whether and how to act, and the options that victims had (or did not have) for survival often hinged on the sharing and application of knowledge. Further, the history of the Holocaust is inherently transnational, transregional, and transcultural. Thus, it becomes increasingly tenable to think of Holocaust history as one of knowledge being exchanged across boundaries—of knowledge on the move.

Employing knowledge movement as a lens through which we can better understand the mechanisms of the Holocaust falls in line with current research trends. It encourages an examination of history from below and directs the historian toward the experiences of subaltern groups who may not have left behind traditional forms of documentation, or who may not have had access to readily available communication methods. This conceptualization allows for a broad and creative exploration of what constitutes “knowledge”: a rumor, a song, a passport, or a memory object may all be important and exchangeable forms of knowledge in the history of the Holocaust. Further, this approach promotes an understanding of subaltern and victim pluralism and heterogeneity, as knowledge was exchanged in distinct ways by and among members of different groups. It also encourages the exploration of human interconnectedness through information networks in local, regional, and transnational settings, and supports the study of victims’, bystanders’, and perpetrators’ day-to-day experiences of producing and exchanging knowledge. These critical new methodological and theoretical approaches were seen in the six panels and sixteen papers that were presented throughout the two-day workshop.

The first panel, chaired by Sören Urbansky, focused on how Jews transmitted knowledge to fellow Jews during and after the Holocaust. Christine Schmidt and Dan Stone shared their research on Holocaust-era letters found in the collections of London’s Wiener Holocaust Library, which explored how letters were used not only to transmit but also to produce knowledge about the Holocaust, and introduced to the workshop a helpful discussion of “information” versus “knowledge”—a conceptual debate that remained a common thread throughout the workshop’s six panels. Laurien Vastenhout presented research on the transnational exchange of knowledge between Jewish councils in occupied Western Europe. She focused on the Association des Juifs en Belgique’s role as an interlocutor that transmitted information about Belgian Jews to concerned family members and friends abroad, provided aid to arrested individuals, and acquired knowledge about the fate of Jews deported to Eastern Europe. Laura Hilton explored the liminal space between true and false knowledge and its deliberate or unintended transmission in her paper on Jews and rumor culture in postwar Germany. She showed how conspiracy theories involving Jews continued to figure into rumors spread by non-Jewish Germans—primarily by individuals hoping to distance themselves from, or implicate Jews in, the atrocities of the Second World War—in the years immediately following the Shoah.

The second panel, chaired by Sarah Ernst, looked at different cases of informal knowledge distribution. Felix Berge shared his research on how Holocaust knowledge was passed via informal communication methods among members of German majority society during the Second World War. Helena Huhak and Andras Szecsenyi presented on the exchange of knowledge in Bergen Belsen’s Hungarian Camp among the “exchange Jews” of the Kasztner action (a Hungarian Zionist rescue operation that involved negotiations with the SS) and how it impacted the mood, activities, and narratives shared by those involved. Jan Lanicek’s paper moved beyond traditional understandings of Holocaust geographies to show how knowledge was transmitted through family networks between Australia and Europe. Despite the Australian government’s ban on correspondence with individuals in enemy territories, informal family networks, as well as formal aid networks, made it possible for individuals in Australia to receive important information about loved ones and the realities of the war in Europe.

Chaired by Alexia Orengo Green, the third panel focused on the transnational exchange of knowledge during and after the Holocaust. Katarzyna Person presented her research on the search for retribution among Polish Jews in the postwar period and showed that survivors often relied on trans-territorial and transnational information networks to seek out and enact revenge on perpetrators. Examining Sephardi immigrants in wartime France, Robin Buller’s paper conceptualized passports and citizenship as forms of knowledge. These knowledge documents could, in different ways and at different stages of the war, be used by perpetrators to target victims or by victims to evade arrest through consular intervention and cross-border escape.

Wolf Gruner moderated the fourth panel, which discussed art as one form of knowledge production and communication. By introducing various musical pieces composed by prisoners from different concentration camps, Anintida Mukherjee explored how music helped camp prisoners persevere and how a musicological examination of the Holocaust can reveal to historians new details about prisoners’ responses, interpretations, and experiences. She showed how studying musical compositions can lead to a better understanding of the function music played as a form of knowledge, especially in reconstructing emotional memories after the Shoah. Ella Falldorf focused on the circulation of visual knowledge by examining various artist-inmates and artist-survivors of Buchenwald. By exploring the creative efforts of different artists and attempts to control the visual imagery of concentration camps during and after the war, she centered Buchenwald as a place of wartime and postwar agency for artist victims of the Nazis.

The fifth panel, chaired by Paul Lerner, explored various forms of knowledge production from below. Paula Chan presented her research on Soviet Jewish survivors’ interactions with the Extraordinary State Commission—an agency dedicated to investigating Nazi crimes on Soviet soil—showing how Jewish engagement shaped the nature and scope of the Commission’s work. Pointing to the overlapping interests of Holocaust survivors and Stalin’s government, she argued that this relationship enabled the Soviet state to reestablish and retain control for another four decades, until long after the fragile alliance between survivors and the state disintegrated. Izabela Paszko spoke about informal knowledge circulation concerning mass killings and the fate of deported Jews and Poles in occupied Poland. Focusing on the example of Zagłębie Dąbrowskie, she brought new perspectives to our understanding of the social aspects of the Holocaust by highlighting the propagandistic potentials of rumors as well as questioning the extent to which victims believed rumors about atrocities. Caroline Mezger presented her research on forced migrants as agents of Holocaust knowledge during the Second World War through a comparative analysis of three local case studies in South Tyrol, Vienna, and Yugoslavia. By analyzing subversive material from the forced migrants as well as state agents, she showed how different groups of displaced people employed similar informal communicative strategies to negotiate their displacement.

The sixth and final panel examined knowledge as a form of agency. Centered around survivor and refugee networks during and after the Shoah, it was chaired by Barnabas Balint. Jonathan Lanz examined how individual survivors of the Theresienstadt Family Camp, a subsection of the Auschwitz II-Birkenau complex, were able to write the history of their experiences through the maintenance of a postwar global survivor network. The role and function of transnational Landsmannschaften (Jewish hometown associations) networks during and after the Shoah was discussed by Anne-Christin Klotz. She pointed to the crucial role of connections between people from the same places to surviving wartime and postwar environments. Tamara Gleason Freidberg analyzed the role antifascist Yiddish speakers played in disseminating news about the Shoah in Spanish by integrating into various antifascist groups in Mexico City. She showed how they were part of broader non-Jewish antifascist groups as well as local Yiddish organizations, and functioned as translators and transmitters of subversive information.

In a final roundtable discussion, led by Wolf Gruner, participants reflected on the themes and trends that were brought to light by the workshop’s focus on knowledge movement during the Holocaust. The presented research clarified that the definition of knowledge depends heavily on historical contexts, and that knowledge can take on various forms and fulfill multiple functions in different settings. Thus, knowledge can be built, constructed, transmitted, narrated, documented, and imagined but it can also be resituated and perceived. Furthermore, it can show up as art, a form of resistance, or a rumor. Knowledge can also empower, limit, or harm an individual. As this workshop showed, the methodological approaches to migrant history and the history of knowledge help open up new research questions and methods in Holocaust Studies.

Having a conference on information networks during World War II in Los Angeles during a time of war and mass displacement in Eastern Europe felt strangely removed from contemporary realities. However, it also underscored that the workshop’s topics are now more relevant than ever. Indeed, it became clear that many of the issues that plague society and that threaten global peace at this moment were echoed in the historical subjects presented, such as fake news, information exchange between authorities and civil society, the role of migrants and refugees in making knowledge, knowledge accessibility, and the potency of knowledge networks.

Workshop at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, April 3-5, 2022. Cosponsored by the Pacific Office of the German Historical Institute Washington and USC Dornsife Center for Advanced Genocide Research. Conveners: Robin Buller (GHI Washington, Pacific Office Berkeley), Wolf Gruner (USC Dornsife Center for Advanced Genocide Research), Anne-Christin Klotz (GHI Washington, Pacific Office Berkeley). Participants: Barnabas Balint (Oxford University), Felix Berge (Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History, Munich), Paula Chan (Georgetown University), Sarah Ernst (University of Southern California), Ella Falldorf (University of Jena), Tamara Gleason Freidberg (University College London), Laura Hilton (Muskingum University), Heléna Huhák (Institute of History of the Research Centre for the Humanities, Budapest), Jan Láníček (University of New South Wales, Sydney), Jonathan Lanz (Indiana University Bloomington), Paul Lerner (University of Southern California), Caroline Mezger (Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History, Munich), Anindita Mukherjee (Ashoka University), Alexia Orengo Green (University of Southern California), Izabela Paszko (Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History, Munich), Katarzyna Person (Jewish Historical Institute Warsaw), Christine Schmidt (The Wiener Holocaust Library, London), Dan Stone (Royal Holloway University of London), András Szécsényi (Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security, Budapest), Sören Urbansky (GHI Washington, Pacific Office Berkeley), Laurien Vastenhout (NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Amsterdam)

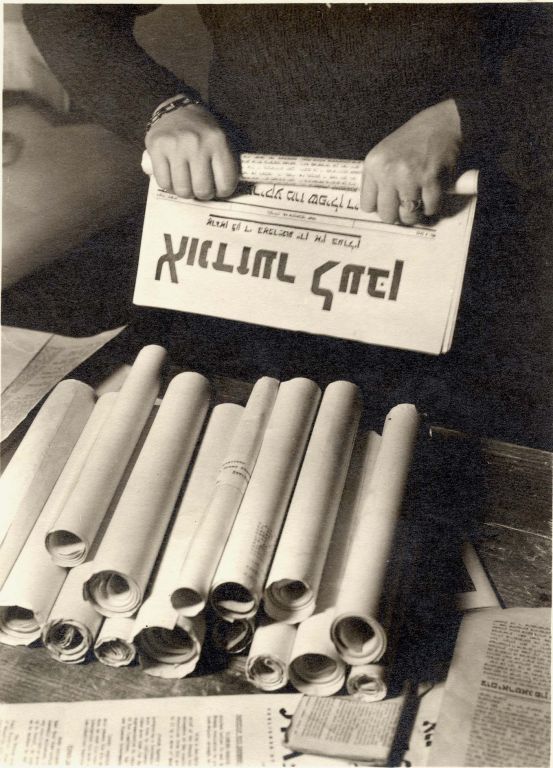

Workshop image courtesy of the Yad Vashem Photo Archive, Jerusalem.