Holocaust Geographies Collaborative November 2016 Visit (Summary)

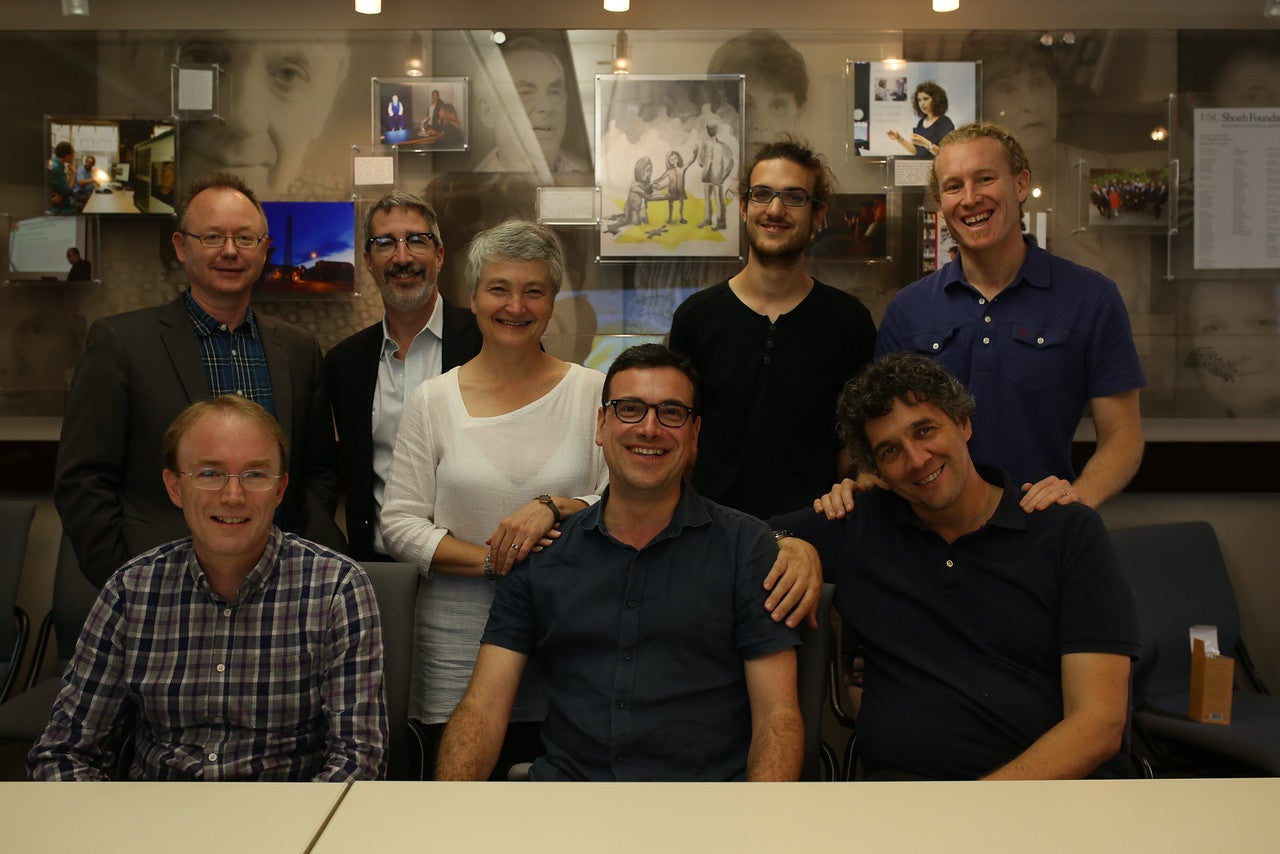

Holocaust Geographies Collaborative Makes A Return Visit to the USC Shoah Foundation Center for Advanced Genocide Research

After the Lessons and Legacies conference in November, the Holocaust Geographies Collaborative made a return visit to the USC Shoah Foundation Center for Advanced Genocide Research for two days to work together, present their continuing research that they shared at the conference, meet with Center staff, and plan next steps in their collaborative project.

Tim Cole (University of Bristol), Alberto Giordano (Texas State University), Paul Jaskot (DePaul University), and Anne Knowles (University of Maine) were accompanied by Paul Rayson (Director, University Centre for Computer Corpus Research on Language, Lancaster University), Erik Steiner (Creative Director, Spatial History Project, Stanford University), and Maël Le Noc (PhD student, Geography Department, Texas State University).

The research since their last visit has focused on the analysis of a small set of transcripts of interviews from the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive. They attended a summer workshop at Lancaster University to be trained in Corpus Linguistics methods. The team experimented with a variety of methods to examine and analyze the text in the transcripts:

– Concordance – words in context

– Collaction – which words are near other words

– Frequency list – simple count of words

– Keyword list – relative frequency of words

– Tagging – parts of speech, semantic categories

Through each of these methods, they discovered different things. When analyzing the semantic categories of the words in the transcripts, they discovered that location and direction; moving, coming, and going; and geographical names are all major semantic categories represented in the transcripts. As geographers and historians, this is significant to this group.

They shared many fascinating findings they have made so far using each of these methods. For example, they discovered some intriguing differences in the transcripts related to gender. In the English language testimonies they analyzed, in women’s narratives, the word “we” occurs more often than “I.” When looking at word clouds for the words most often used in testimonies, “husband” and “sister” prominently appear in the word cloud for women’s testimonies. However, the same is not true for men. “Wife” and “brother” do not occur with the same frequency and thus are not prominent in the word cloud for men’s testimonies. These gender differences raise very intriguing questions. Did men and women experience different things during the Holocaust? Or is this just a case of men and women narrating their experiences differently? For this group interested in social relations and changes of social relations over time and in space, the use of “we” in the testimonies — and even the number “five,” which the group also searched for and analyzed – may point towards the centrality or significance of social relations to survival.

As these methods of analysis are extended to other languages, the comparative implications are profound. These same tools could be applied to examine geographical and temporal differences in the interviews. They could be used to broadly analyze differences between interviews from different institutions or between individual interviewers. In addition to identifying broad commonalities across testimonies, these methods can be employed to identify what is exceptional and unique in Holocaust experience.

Consistent with their creative, experimental, and groundbreaking research so far, the group is experimenting with how to visually represent what they are analyzing and discovering. This kind of data has never been visualized before so they are working together to pioneer new modes of visualization.

Moving forward, one of their central concerns is how to scale up their research, analysis, and visualization beyond the small set of transcripts they have worked with so far to see what they can discover across hundreds, thousands, and eventually tens of thousands of testimonies. They are eager to discover how these computational and visualization methods can contribute to a more integrated history of the Holocaust.