When the Floods Came

The day the first drops of winter rain spattered onto the parched earth, Southern California’s ranchers heaved a collective sigh of relief. It was Nov. 14, 1861, and the region was in the grip of a severe drought. The ranchers had been praying feverishly for rain for months. At long last, they thought, as they tipped their faces heavenwards to the dark clouds gathering overhead. Little did they know that they — along with the rest of the Pacific West — were about to get far, far more than they had bargained for.

From that day until March 1862, not just Southern California but the entire Pacific Coast was battered by a series of exceptionally intense storms that rolled in relentlessly, one after another, for five long months, creating one of the wettest periods the region has experienced in the past 2,000 years. The succession of cold and warm storms dumped nearly 10 feet of rain in certain parts of California and 60 to 70 inches in many other parts of the state in just 43 days, leaving much of it underwater and bringing flooding all the way down the West Coast, from British Columbia to Baja California.

“Some people have boats and canoes, but people are also using doors, barrels — anything that floats — as makeshift rafts.”The effects were devastating. Up to 1,000 people died in the floods while thousands of animals, including cows, horses and other livestock, perished in the rising waters. Towns and settlements were destroyed and buildings were swept away across California, Nevada and Oregon, as well as communities in what is now Washington, Idaho, Utah and Arizona. In California alone, estimates of property damage ranged in the tens of millions of 1860’s dollars.

In an essay he published on Zócalo Public Square based on an eyewitness account of the floods, USC Dornsife history scholar Will Cowan describes the destruction of the Southern California town of San Salvador in San Bernardino County:

Frenzied, the people fled to higher ground along the far bank, saving little more than the soaked clothes slung over their bodies. Some of the last to escape had to swim to safety … They choked in anguish as the unrelenting Santa Ana River consumed the town, crashing first through the dance hall, melting houses, flushing away cattle, sheep and fowl, the river gentle no longer.

Big Winter

“During those few months, these storms caused some of the most severe floods, freezes and blizzards that have ever been recorded in the history of the Pacific West,” says Cowan, a doctoral student who is writing the first academic study of what he calls “The Big Winter of 1862.”

In Los Angeles, the L.A. River overflowed and the Pueblo was underwater. L.A.’s ranches were devastated, while the many vineyards along the river were destroyed, buried in gritty sand and gravel washed down from the San Gabriel Mountains.

Sacramento was hit particularly hard, as was the Central Valley. Both were flooded four or five times that winter, while Indian mounds across the Sacramento Valley, topped by 300-year-old oaks, were completely washed away by the floods, sadly removing much of the Indigenous landscape.

Fishermen caught freshwater fish off the coast of San Francisco after flood waters flowed out into the bay, creating a black plume of fresh water mingled with soil washed out by the rain. Lakes around Puget Sound in Washington froze hard enough for ice skating.

The Santa Ana and San Gabriel rivers overflowed and intertwined. Swollen rivers and streams across the state burst their banks and the majority of the infrastructure on every river was completely washed away, from bridges to levees. People ran to high ground if they could, but many were not so lucky. Cowan notes countless accounts of houses floating down rivers with candles still burning in them and people screaming from windows for help. Others found themselves marooned on the roofs of their homes, where they had clambered to avoid the rising floodwater.

Swirling around them was a murky, surreal soup containing everything from dressers, pool tables, beds and the water-swollen carcasses of dead cattle to entire barns, lumber mills and once-towering pine and spruce trees. There is even an account of a haystack with livestock perched on it, floating past.

“Some people have boats and canoes, but people are also using doors, barrels — anything that floats — as makeshift rafts,” Cowan says. “It looks almost like a Mad Max movie set in the 1800s, where everything’s cobbled together out of broken objects.”

Among the biggest heroes in this story, Cowan says, were the steamboat pilots who plucked people off roofs and floating logs and out of trees, rescuing hundreds who otherwise wouldn’t have survived.

In this pre-FEMA era, there was a huge humanitarian response to the victims of the flooding.

“People are very willing to give what they have,” Cowan says. “San Francisco takes on thousands of refugees from the Sacramento Valley and donates huge quantities of food and clothing. There are stories of women staying up day and night sewing and putting together care packages.”

But for all the heartwarming tales of heroism, generosity and self-sacrifice, there were also heartbreaking reports of human suffering.

One of the most terrifying and terrible accounts, Cowan says, concerns Long Bar, an island on the Yuba River, northeast of Sacramento. A popular mining area, the island was home to some 1,000 Chinese migrants who had built a temple there with a protective drawbridge.

“When the floods came, the Chinese miners all go into their temple and raise the drawbridge, but the water eventually rises up above the walls and completely subsumes their town,” Cowan says, noting that 500 Chinese miners are believed to have perished.

Meanwhile, the rain keeps falling. From Redding to Bakersfield — a distance of 450 miles north to south — and almost 100 miles across, the Pacific West was submerged.

In all, Cowan estimates two dozen towns and settlements were lost to the floods, never to be rebuilt or relocated, among them Champoeg, Oregon; Fort Boise, on the Snake River in Idaho; and Agua Mansa, which incorporated San Salvador and was the precursor to the Southern California city of Riverside and once a key settlement on the trade route between L.A. and Santa Fe, New Mexico.

“The geographic breadth of the effects of this winter is just stunning. That’s part of why I wanted to tell this story,” Cowan says. “There’s really nothing about each one of these individual storms that was so special, although they were certainly big. It’s that they happened in such quick succession and over such a large geography — that’s what made them dangerous.”

A Potentially Lethal Spigot

While the exact cause of these extreme weather conditions is hard to determine with absolute certainty, they probably arose from atmospheric rivers (ARs) — high-intensity, high-density channels of water vapor that funnel water across the Pacific Ocean.

When these channels of water vapor crash into the West Coast, butting up predominantly against the Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountain ranges, they can drop immense amounts of water in rain and snowfall in just a few hours, and bring winds at speeds of more than 60 miles per hour.

“We can think of ARs as the spigot that controls the water in the American West,” Cowan says.

“That winter, a series of these atmospheric river storms kept rolling in, one after the other, from the Western Pacific,”

Cowan says. “This is tropical water and noticeably warmer than your standard winter storms. So, when the warm rain hits the snow, you get this double whammy of both rainfall and melted snow.”

The Earth Archive

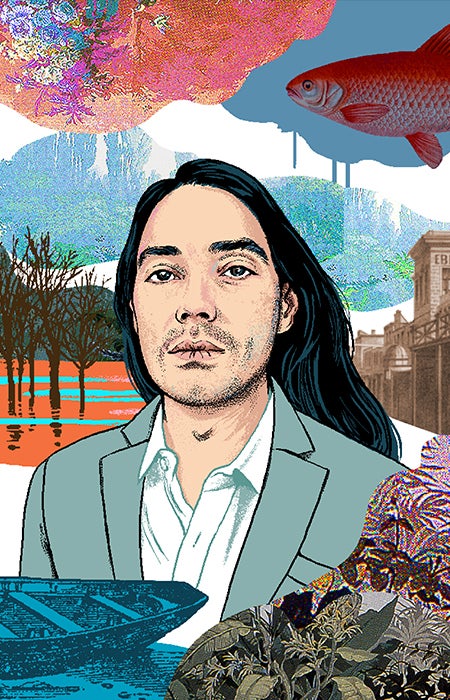

Born in San Bernardino, California, to a teacher and a sheet-metal worker, Cowan grew up in the Mojave Desert.

“That was a living laboratory,” he says. “I’d go out and just observe, which is probably why I’m now so interested in environmental history, ecology and the human experiences of the environment.”

Cowan says his desert upbringing and his Uchinanchu background — his maternal grandmother was born in the Ryukyu Islands — encouraged him to form a deep connection with the landscape.

“I spent so much time outdoors with my parents and with my maternal grandparents, in their gardens learning about traditional foods and plant medicine,” he says. “It’s something that has been part of my life for a very long time.”

After earning a history degree from the University of California, Riverside, in 2003, Cowan worked at a variety of jobs, including teaching at a public school, playing music and driving a forklift, before historian and urban theorist Mike Davis suggested he contact USC Dornsife’s William Deverell, professor of history and spatial sciences and director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West.

“Bill was one of the few folks who right away understood my vision for the project and thought it was an urgent history to tell,” says Cowan.

Describing himself as a historian first and an amateur geoscientist second, Cowan has taken courses in forest ecology, fire ecology, California vegetation and climate change.

“As an environmental historian, I hate to limit myself to only written documents but try to use any evidence that helps us get closer to knowing what happened and why,” he says. “For me, learning to read the landscape is as important as learning how to navigate the archives.”

In his research, Cowan relies on typical sources, such as letters, diaries and newspapers, but also integrates tree-ring studies and sea-floor and lake core samples, using research by USC Dornsife’s Sarah Feakins, associate professor of Earth sciences.

“Some folks will say, ‘How do you know this really happened?’ because newspapers in the 19th century did tend to exaggerate,” Cowan says. “My research shows there are not only firsthand accounts of people who experienced it, but there’s also what I like to call ‘The Earth Archive’ — data embedded in our landscape, whether in trees, riverbeds or the ocean floor, that can give us a very accurate history of wet and dry periods — and 1862 was historically, extraordinarily wet.”

“For me, learning to read the landscape is as important as learning how to navigate the archives.”An Altered Landscape

The implications of the floods were far-reaching for the people, towns and settlements affected. Sacramento built levees and raised the level of the city by 10 feet. An ill-advised attempt to create a levee by building a wall down the middle of the Sacramento River was doomed to failure.

“There was a lot of hubris involved, but it was that hubris that helped them develop the flood control systems that now protect the city,” Cowan says.

“Through the major channelization and damming projects of the Army Corps of Engineers in the 1930s, we pretty much put the rivers of the West in a straitjacket. And for very good reason, when you see how damaging these floods can be.”

But flood prevention measures have also dramatically reshaped our landscape, and the consequences of that, Cowan says, are something we should think hard about.

“From Mount Shasta all the way down to Bakersfield, basically the whole Central Valley was one stretch of water,” Cowan says. “For instance, before it was drained — a project begun following the floods — the now nonexistent Lake Tulare, at one time the largest body of water west of the Great Lakes, covered 700 square miles, stretching several hundred miles long and some 50 miles wide.

“Depending on the season, one could take a steamboat from San Francisco to where Bakersfield is now,” Cowan notes. “Before the arrival of European settlers, the Central Valley was a maze of wetlands, rivers and Native villages, not at all like we see it today as this big, often dry, dusty, agricultural zone.”

Looking Forward

Could California succumb to such disastrous flooding in the future? Cowan warns that it could.

“The latest research on atmospheric rivers tells us that it’s only a matter of time,” he says. As the climate warms, air can hold more moisture, thus making ARs more potent. More powerful ARs could lead to more powerful storms, potentially compromising our flood control systems.

“Most of the Army Corps people tell us they believe that the current infrastructure will hold, that we’ll easily handle a 200-year flood event. But my fear again isn’t so much about one storm, it’s if we get several storms in a row, as occurred in 1861–62.”

As Cowan points out, if the reservoirs are filled after one or two very wet storms and then we have a third, where will that water go?

“If a rapid succession of strong storms flow through the system, it will not be able to move the water or absorb it fast enough to avoid an overflow,” he says.

“As Californians, we’re in the Ring of Fire and of course should be concerned with earthquakes, but I also think that we should be concerned about atmospheric rivers and the potential for these giant floods that would bring with them the danger of landslides, high winds and heavy snow.”

Cowan raises the possibility of an ARkStorm (Atmospheric River 1,000 Storm) — a hypothetical but scientifically realistic “megastorm” scenario developed and published by the Multi-Hazards Demonstration Project of the United States Geological Survey. Based on historical events, it describes an extreme storm that could devastate much of California, causing up to $725 billion in losses, mainly from flooding, and affecting a quarter of California’s homes.

“It’s predicted to cost three times what one big earthquake would cause in terms of infrastructure damage and economic losses,” Cowan says.

The name “ARkStorm” reflects the original projection of the storm as a 1-in-1000-year event. However, more recent data suggests that the actual frequency of the event is likely to be in the 200-year range.

Cowan notes that the 2016–17 winter was the wettest on record in 122 years. The rainfall that season was nearly equivalent to that of 1861–62, but the timing of the storms was different in critical ways. The storms of 2016–17 were spaced further apart, allowing time for runoff to infiltrate the ground or flow through the system.

After studying the history of the great storms of 1861–62, Cowan is proposing solutions to protect California from both future floods and drought.

Instead of having a water management system that flushes rainwater to the ocean as fast as possible, perhaps we can develop a more hybridized system that will still protect neighborhoods and agricultural land from overflows, but allows some flooding to remain on the land, he suggests.

“Spillways and sponge-like wetlands can become both a flood mitigator, absorbing tons of rainwater, while also helping recharge aquifers for times of drought.”

Understanding this history is clearly of vital importance, he stresses, both in grasping the climate challenges we are facing, educating the public about ARs and, as these storms bring fresh water to the West, also creating a sustainable water future.

“I don’t want to be a doom-and-gloomer,” Cowan says of his warning that California could face devastating floods in the future, “but I do feel very strongly that we need to be paying a lot more attention to this atmospheric phenomenon and its history.”

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine ’s Fall 2020/Winter 2021 issue >>