UN climate negotiations end on shaky geopolitical ground, but I see reasons for hope

The 2024 United Nations climate talks wrapped up two days late, with an ending fitting that of a geopolitical reality TV show, complete with walkouts and recriminations.

Countries agreed on a new climate finance target on Nov. 24, 2024, promising to provide at least US$300 billion annually by 2035 to help developing countries build clean energy systems. But it was far less than the $1.3 trillion vulnerable countries were calling for.

The conference also delayed a debate over how to move forward on a 2023 agreement for all countries to contribute to “transitioning away from fossil fuels” and to submit climate pledges aligned with the 1.5C limit.

Some people may be ready to write the epitaph for global progress against climate change. But as someone who teaches global environmental politics and has followed international climate talks for years, I see both practical and moral reasons to remain hopeful.

The battle to keep the 1.5 C goal alive

In 2015, the world’s nations agreed as part of the Paris climate accord to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), with an aspirational target of 1.5 C (2.7 F). This target is important, but sometimes confusing. It is rooted in science, but it is not a singular “tipping point.”

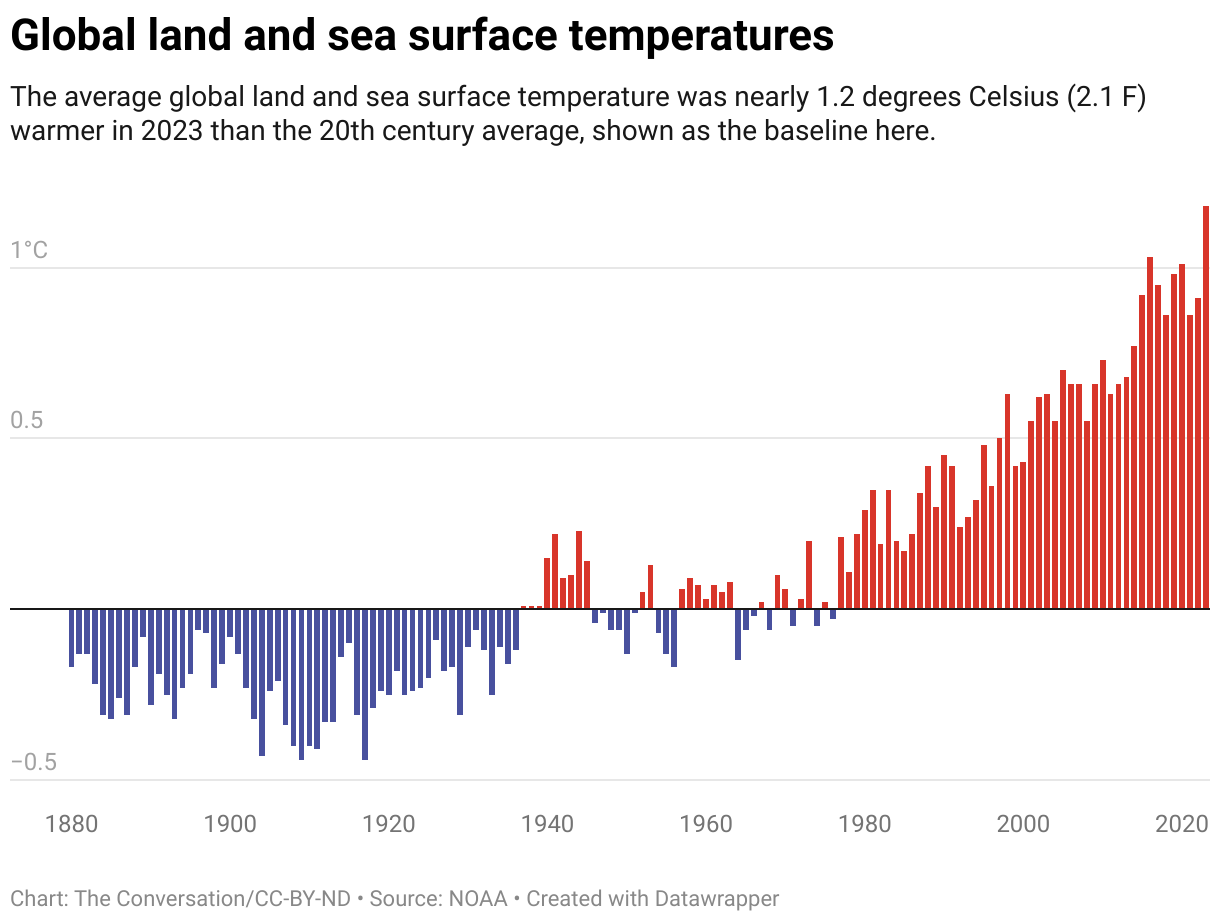

As the planet warms beyond 1.5 C, multiple large-scale climate shifts will become more likely.

Ocean circulation is already slowing, coral reefs face increasingly common mass bleaching events as the oceans heat up, and Arctic permafrost is thawing, releasing greenhouse gases that further fuel climate change. Rising temperatures are also fueling increasingly frequent and more damaging heat waves, droughts, wildfires and flooding that put human lives and livelihoods at risk.

Recognizing these risks, the Paris Agreement was widely heralded, and many countries have made progress in lowering their emissions in the decade since. However, not all countries are pulling their weight.

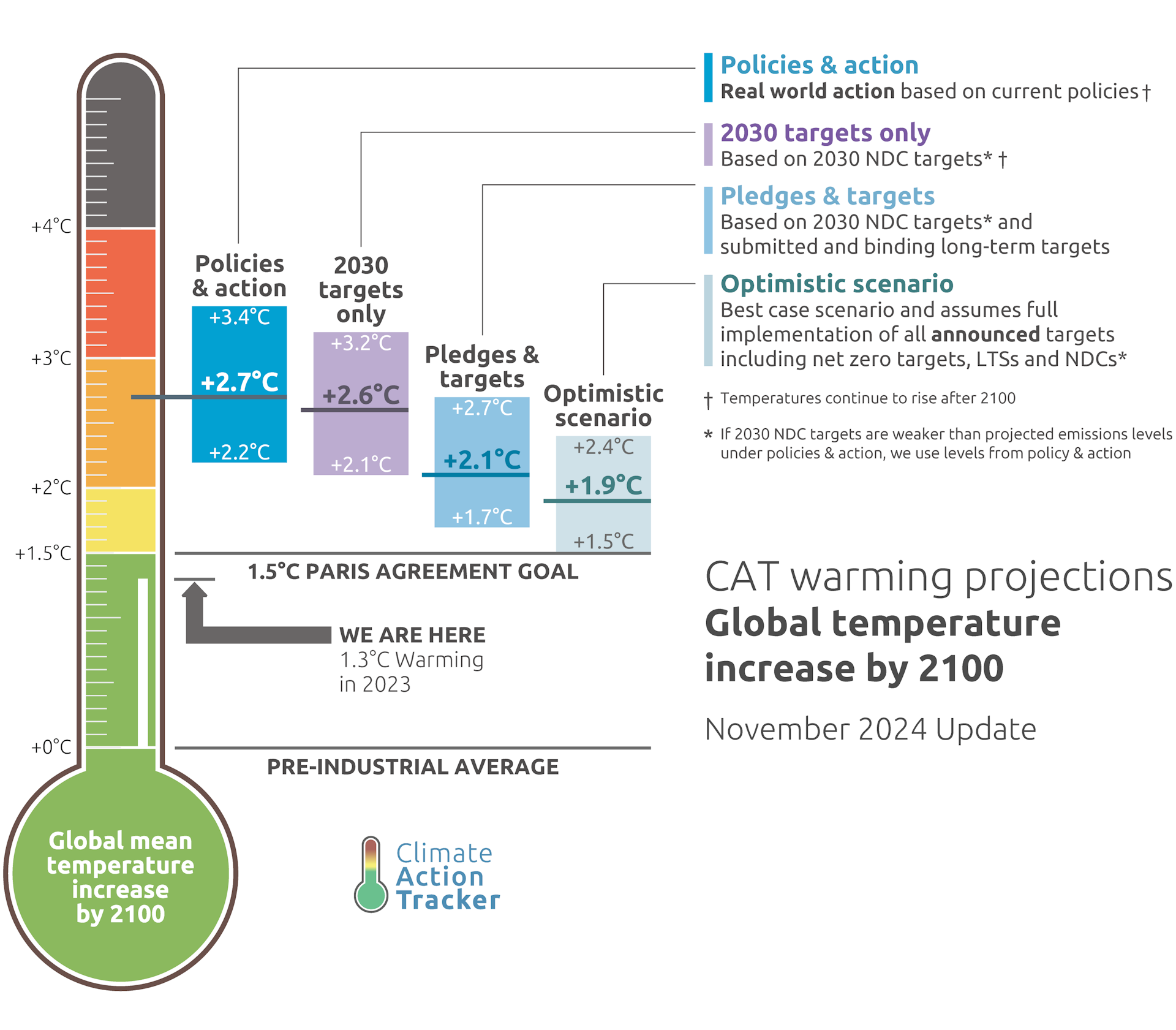

In 2023, the U.N. acknowledged that the countries’ current commitments for addressing climate change, known as nationally determined contributions, or NDCs, would still result in a catastrophic 2.5 C to 2.9 C (4.5 F to 5.2 F) of warming by 2100.

The World Meteorological Organization issued a “red alert” in November 2024 that the world is on track to overshoot the 1.5 C goal this year. It notes that this overshoot can be temporary — if countries take greater action.

How the world can still meet the Paris goals

Countries can still turn the tide on climate change.

The outcomes of the 2023 climate talks provided a road map for countries to increase their efforts toward net-zero emissions:

- Triple renewable energy capacity globally.

- Accelerate a phasedown of coal power.

- Transition away from fossil fuels.

- Accelerate zero-emissions and low-emissions technologies.

- Cut methane and other noncarbon dioxide emissions.

- Reduce emissions from road transport.

- Phase out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.

Many countries are making progress on this transition.

Among developed countries, Norway is on track to phase out of fossil fuel vehicle sales in 2025. China has become a leader in renewable energy. It pledged in 2020 to double its renewable energy capacity by 2030, and, thanks to solar power deployment, it expects to complete that goal in half the time.

Other nations, including the U.K., Greece and Denmark, have embarked on major efforts to scale down coal power, with Portugal being the first to hit zero coal.

An important mechanism of the Paris Agreement is the expectation that countries will ratchet up their commitments every five years. The deadline for these new climate goals is early 2025, and some countries have gotten a head start.

Brazil announced its new climate commitments during the climate conference, pledging to reduce emissions 67% by 2035. The United Arab Emirates submitted a commitment to reduce its emissions by 47% compared with its 2019 baseline emissions. Other countries signaled their intentions in high-level statements. Belgium announced a doubling of its climate finance contribution.

These new announcements are a good sign of continued global support for the Paris Agreement goals.

Additionally, the conference made progress on agreements to reduce non-CO₂ emissions, namely methane, nitrous oxide and hydrofluorocarbons — also known as climate change “super pollutants” because of their extreme global warming potential.

Why the Paris Agreement will survive a second Trump presidency

There is no doubt that Donald Trump returning as U.S. president will pose significant roadblocks to efforts to slow climate change. As a candidate, he talked about throttling back U.S. efforts, including cutting funding for clean energy and eliminating regulations on the fossil fuel industry.

But efforts to deal with climate change are bigger than one person or even one country.

While Trump has declared that he will pull the U.S. out of the international Paris Agreement again, influential people are advising him to reconsider. Exxon Mobil CEO Darren Woods argued that a U.S. withdrawal would leave a hole at the global negotiating table.

Even if Trump does pull the U.S. out of the treaty, which he can do after a one-year waiting period, that doesn’t mean pro-climate actions in the U.S. will simply stop or that the agreement will fall apart.

There are commonsense business reasons to push climate efforts forward, starting with the fact that clean energy is now cheaper than fossil fuels in much of the world. Nearly 1 in 5 vehicles sold in 2023 globally were electric. In the U.S., heat pump sales are beating gas furnaces for the third straight year.

A withdrawal from the Paris Agreement also does not prevent states and cities from continuing their progress against climate change.

In fact, after Trump announced he would withdraw the U.S. from the agreement in 2017, several U.S. states doubled down on their climate commitments. Hawaii, for example, passed legislation to be “Paris compliant” and get to net-negative emissions, meaning it will sequester more emissions than it emits.

California continues to report falling emissions even with a growing economy. The state sued several large oil and gas companies for deceiving the public about climate change.

Moreover, a U.S. retreat from the Paris Agreement would not be an embargo on individual actions. Engineers and scientists will continue to create innovative technology to reduce emissions and slow climate change, and corporations will reap the economic benefits of energy efficiency and clean energy market leadership.

This acknowledgment has given rise to calls for a blend of optimism and pragmatism.

Looking ahead to 2025

Next year’s COP30, to be held in Brazil, is important because countries face a deadline for setting new targets. Overall, their current policies still fall short of the 1.5 C goal.

Calls for greater commitments are not just optimistic, they are economically and morally compelling.

For one, the future cost of inaction now is greater than the cost of action, so concerted decisions to delay emissions cuts now will only harm countries in the future.

Morally, the international community has a responsibility to mitigate suffering. This is the very nature of long-held international norms and laws, such as the “responsibility to protect,” and reiterated in Pope Francis’ calls for global environmental responsibility.

While the climate will breach the 1.5 C warming limit, every fraction of a degree matters. I believe it is crucial that countries, states, business leaders and people everywhere continue the shift toward cleaner energy to minimize the impact.

Researchers Emerson Damiano and Lauren Segal, students in environmental studies at the University of Southern California, contributed to this article.![]()

Shannon Gibson, Associate Professor of International Relations and Environmental Studies, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.