Student researchers dive into the deep

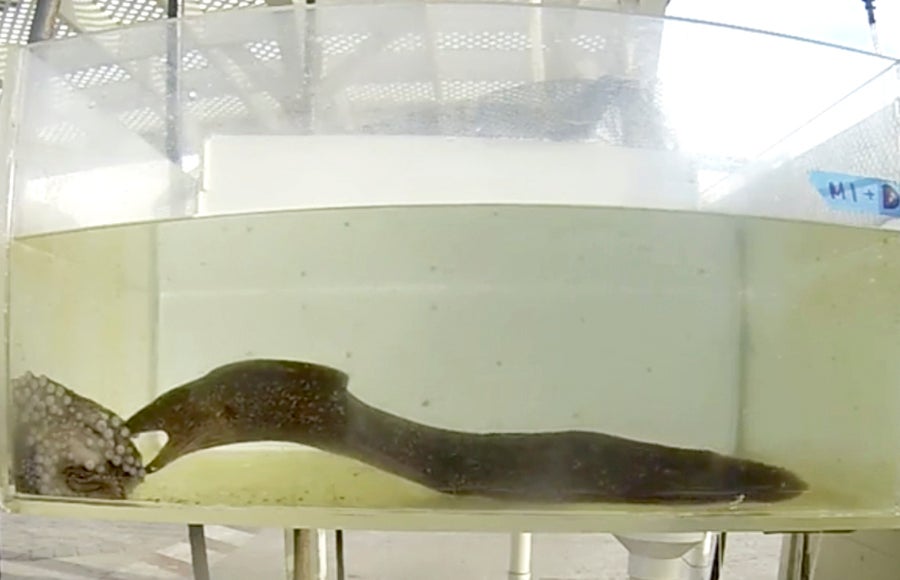

A Verrill’s two-spot octopus readies her defenses. And for good reason. With a moonstruck grin, a California moray eel squiggles into frame. It’s one of this octopus’ only rival predators in the reefs around Southern California’s Santa Catalina Island, and the eel has a disarming plan to make a meal of her. Literally.

You might expect the scene to be narrated by Sir David Attenborough, the British naturalist who, in his gentry whisper, invites us to behold the wonders of nature. But there is no voiceover. No suspenseful build. Because this is no nature documentary.

This is an undergraduate research internship.

Nathalie Benshmuel, a junior majoring in environmental studies at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, spent her summer conducting behavioral analysis using hours of video in which octopi were pitted against eels in a controlled laboratory environment.

She is one of 19 USC students who recently completed a virtual Zinsmeyer Summer Internship at the USC Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies, headquartered at USC Dornsife.

In a more traditional year, these experiences would have included a fieldwork component, likely at the USC Wrigley Marine Science Center on Catalina Island. When the COVID-19 pandemic compelled students to shelter-in-place, plans understandably changed. While it’s easy to assume that environmental projects sans the environment suffer ontological fallacy, the virtual internships proved to be engaging and memorable learning opportunities.

“This was my first exposure to concrete research,” said Benshmuel, who studied the footage from her home in Tennessee. “It was my first approach to creating a researchable question and pinpointing something in which you can find results.”

She hypothesized the eels would use specific strategies for hunting different sexes of the two-spot octopus, based on variation in defense mechanisms related to contrasts in their reproductive anatomy. Her research indicates that eels are able to detect certain pheromones in the females, provoking a more active hunt.

Lingua scientia [the language of science]

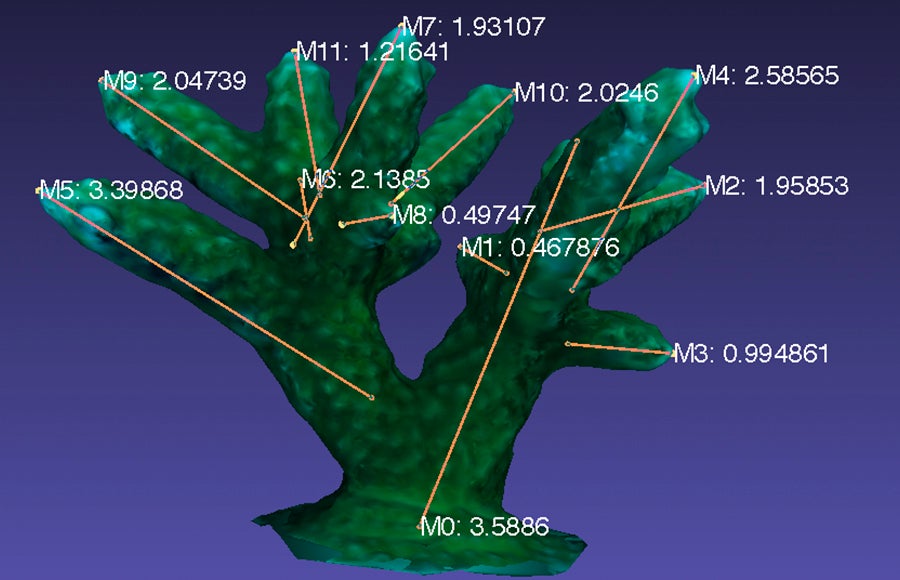

Under the guidance of faculty and graduate student mentors, interns worked on a wide range of projects related to marine ecosystems. From generating data on coral growth using 3D models of colonies in the Florida Keys to exploring the genes that allow “sea fireflies” to glow Santorini blue, students helped uncover new knowledge about the natural world — even while at home in their pajamas.

“We specifically asked mentors for projects with components that could be worked on remotely,” said Diane Kim, director of undergraduate programs at the USC Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies. “A lot of research relies on existing datasets and things that can be analyzed on virtual platforms.”

Many of the interns had never used the specialized tools their projects required to write codes, manipulate data and analyze the results. For example, Harold Carlson, a junior majoring in biology and geology, worked on a team that used the R programming language and software for statistical computing and graphics. Before conducting any analysis, he first had to learn the code. Each day, Carlson’s advisor would send new instructions to practice, challenging him to determine how he would apply it to the project.

Science collaboration

Some of the interns worked on questions related specifically to their career goals. But many found the process of collaborative science to be more edifying than the actual experiments — from the mentor/mentee relationship to the computational and writing skills that kept projects moving forward.

Benshmuel developed a unique bond with her advisor, Kelley Voss, a Ph.D. at the University of California, Santa Cruz and a USC Wrigley summer research fellow. “Every other day we had a scheduled Zoom meeting, which was very formal in a sense,” said Benshmuel. “But she would also be a mentor, doing things like helping me look at grad schools.”

In addition to their research, interns participated in many of the activities that are always offered through the Zinsmeyer Internships, such as resume development, weekly seminars on marine science topics and communication workshops. Students have often been surprised by the ancillary lessons they take from the program, and the pandemic put some of these lessons in new context.

“The highlight of my summer was learning that to be a researcher is to be vulnerable,” said junior Jonathon Lin, who is majoring in environmental studies. “You need to accept confusion and uncertainty in order to get results.”

Andy Zinsmeyer ’63, who served on the USC Wrigley Institute Advisory Board for more than a decade, has enjoyed opportunities throughout the years to meet with students who benefit from the support he provides to fund the internships. “In some cases, the summer program changes their life,” Zinsmeyer said.

Too legit to quit

While the summer internships have wrapped-up, Carlson is still closely monitoring the status of his team’s project, which explores whether there are easier ways to assess the health of Southern California’s marine ecosystem by using biodiversity data. Along with eight other undergraduates working alongside graduate student mentors and Professor of Biological Sciences Sergey Nuzhdin, Carlson examined ecological patterns over different landscapes.

His portion of the project was to explore changes in biodiversity of invertebrates such as snails, crabs and shrimp on the seafloor as sample sites get further apart. By looking at the rate of these changes, Carlson and his colleagues found that measurements of this kind are potentially more useful in nearshore environments, such as estuaries, than they are in offshore environments.

The lab team worked together to produce reports about their findings, which were then compiled into a draft of a scientific paper that will be submitted for publication in the near future.

“I was impressed that the internship happened at all under these circumstances,” Carlson said. “But I never expected to be a co-author on a paper while sitting in my bedroom this summer.”