A revived PhD program mentors a new generation of anthropologists

In brief:

- USC Dornsife’s anthropology department relaunched their PhD program, which hasn’t graduated a student for more than a decade.

- The rebooted program emphasizes topics with hands-on applications to the public, like medical and visual anthropology.

- Students in the program will be encouraged to pursue training with other USC schools, such as the USC School of Cinematic Arts and the Keck School of Medicine of USC, as well as USC Dornsife.

“The last thing the world needs is another 20th-century PhD program,” says Peter Redfield, professor of anthropology and chair of the anthropology department at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. “We needed to rethink PhD training.”

This past fall, the anthropology department relaunched their PhD program, which has lain dormant since 2009. The relaunch was also a revisioning, sparked by the large cultural and technological shifts in the field as well as higher education at large.

“We couldn’t just plug it back in and pretend that this was the year 2000,” says Redfield, who holds the Robert F. Erburu Chair in Ethics, Globalization and Development. The renewed program emphasizes fields such as medical and visual anthropology, encouraging students to pursue filmmaking or investigate how health is shaped by social forces. Collaboration with the Keck School of Medicine of USC and USC Cinematic Arts gives students access to resources across the USC campus.

It’s all designed to produce graduates prepared for the modern workforce who have also undergone the scholarly rigor of a PhD program.

“Many of the people who will be coming through the program are going to have careers that will not be strictly academic,” says Redfield. “We want to encourage them to develop other skills while also pursuing the academic project of the PhD dissertation.”

Inspiration from legends and future needs

For the program’s reboot, the department looked at both the past and the future for inspiration.

Barbara Myerhoff founded the Center for Visual Anthropology at USC Dornsife in the 1970s. (Image source: Wikimedia Commons.)

The department has produced important works of visual anthropology for almost 50 years. In the 1970s, Barbara Myerhoff founded the Center for Visual Anthropology at USC Dornsife. Her short film “Number Our Days,” which explores the lives of elderly Jews socializing at a senior center in Venice, California, won an Oscar in 1976.

After her death in 1985, Professor of Anthropology Timothy Asch served as the center’s director until 1994. He produced over 70 ethnographic films, often in collaboration with fellow anthropologists in Afghanistan and Indonesia.

“The department has had a rich tradition of filmmaking, and that’s something we wanted to retain but also broaden,” says Redfield. “We live in a very complex, media-saturated world now where everyone makes films on their phone all the time. It’s a different environment than it was even 20 years ago, let alone 30 or 40.”

Medical anthropology has been booming in recent years, says Redfield, partly because health care is playing an increasing role in our lives and because discussions around inequality in medical care have seen an uptick, particularly during the pandemic.

“People who work in health care have become increasingly aware of intercultural issues, of structural inequities, of the fact that access to health care is not equal and that medical training does not produce uniform results,” says Redfield, who has written a book on the ethics of the organization Doctors Without Borders.

The training acquired in anthropology makes graduates well-suited to analyzing these societal problems. “Anthropology has always attempted to speak about human problems from a geographically broad and historically deep perspective,” says Redfield.

“This tradition can be extremely valuable in almost any line of work. Anthropology isn’t always good at coming up with solutions, but it’s good at encouraging people to recognize problems, cross boundaries and ask questions.”

New kids on the block

A revived program was a good opportunity to bring in some fresh faces to the department. One of these new arrivals is Fiori Berhane, assistant professor of anthropology, who researches the politics of Europe’s African migrants.

Berhane just completed a PhD in anthropology herself, having graduated from Brown University in 2021. This means she’s keenly aware of all the challenges facing today’s PhD students and the need to balance passion with practicality.

“I want students to not only learn the formal things, like how to write grants, but also how to build a sense of confidence, curiosity and the drive to continue with one’s work,” says Berhane. “Only seeing a PhD through the lens of professionalization is not good in terms of creativity, and only seeing it as a calling is not good for people’s mental health.”

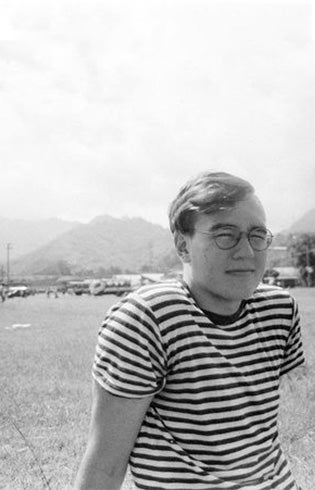

New anthropology professor Seth Holmes spent years traveling with migrant farm workers to study their experiences with health care. (Photo: Courtesy of Seth Holmes.)

Another new arrival, Seth Holmes, Dean’s Professor of Anthropology and Medical Education, focuses on how economic and cultural stressors impact the health and health care of immigrant field workers.

While Holmes was in medical school at the University of California, San Francisco, he noticed that his textbooks often overlooked the ways economic inequities, racism and sexism played a role in health outcomes.

He decided to pursue a PhD in medical anthropology at UCSF and the University of California, Berkeley and began researching how factors like market forces and racism impact migrant field workers and their health care. Holmes spent several years traveling alongside these workers, living in farm camps, picking strawberries, and accompanying workers to clinics. His dissertation culminated in the award-winning book Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies (University of California Press, 2013).

Now at USC Dornsife, he’s excited to help students who might want to add rigorous training in anthropology to another field of study.

“Some of our students will be academics, but many students will go on to do other things like filmmaking, running a museum, becoming a medical doctor or a social worker,” explains Holmes. “Our department is very supportive of students who want to be an academic anthropologist or pursue any of those other careers with a strong anthropological perspective.”

First through the gate

El Whittingham, one of the first PhD students in the program, is working on a documentary on queer communities in Senegal. (Photo: Courtesy of El Whittingham.)

El Whittingham is one of the first students enrolled in the program. Able to speak five languages, Whittingham — who uses the gender-neutral pronouns “they” and “them” — recently completed a master’s in French and Spanish at the University of Washington.

Whittingham hopes to make a large body of work that explores LGBTQ experiences in the post-colonial world. Filmmaking is a way these stories can reach a broader group of people. “It makes anthropology work more accessible and more interesting to a larger audience,” they said.

Currently at work on a documentary that explores underground queer communities in Senegal, where homosexuality is outlawed, Whittingham said the PhD program’s renewed emphasis on film was exactly what motivated them to apply.

“There are only a few universities in North America that focus on visual anthropology and that’s what drew me to the program,” says Whittingham, who has been taking technical classes in the film school along with their anthropology studies. “The resources are endless and you’re encouraged to use those resources.”