Renewed Energy

Jane Lubchenco showed an animation of the world’s peak fishing areas as they were between 1951 and 1999. Darker spots — indicating areas of more concentrated fishing — were limited mainly to water near the coast lines 60 years ago. By the new millennium, however, the hot spots had moved much farther out — to the high seas.

“There are no new places to fish,” Lubchenco said during her lecture, “Seas the Day: A New Vision for Healthy Oceans and Vibrant Communities.” She delivered the presentation at the Tyler Prize Laureate Lectures on April 24 on USC’s University Park campus.

“Also limiting our supply of wild-caught seafood are unsustainable fishing practices and policies, and illegal fishing, which has become a huge global problem,” she said.

Lubchenco, University Distinguished Professor and adviser in marine studies at Oregon State University, is co-recipient of the 2015 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement. She shared this year’s honor with Madhav Gadgil, D.D. Kosambi Visiting Research Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies at India’s Goa University.

Although the geography of their policy-driving research could not be more different, their overall messages are the same: We face formidable environmental challenges, but humans are not powerless to fight against them.

Established in 1973 and administered by USC Dornsife, the Tyler Prize is the premier award honoring environmental science, environmental health and energy that confers great benefit upon mankind. Recipients conduct scientific research and exhibit leadership skills that address the full spectrum of environmental issues. Past laureates include Jane Goodall, the world’s leading chimpanzee expert; former U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop; and several Nobel Laureates.

Jane Lubchenco receives the 2015 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement for her work to protect the oceans by bridging science and policy. Photos by Steve Cohn.

The Tyler Prize Executive Committee and the international environmental community honored Lubchenco and Gadgil at an April 25 ceremony at The Four Seasons Los Angeles in Beverly Hills, California. In addition to being presented with gold medallions, each received a $200,000 cash prize.

“We are incredibly proud to have two distinguished laureates this year, who are standing on the shoulders of the wonderful laureates from the last 41 years,” said Julia Marton-Lefèvre, who recently took over the role of chair of the Tyler Prize Executive Committee.

Gadgil has focused his career on incorporating environmental science into policymaking and public outreach in India and worldwide. He chaired the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel for India’s Ministry of Environment and Forests, which published an iconic recommendation for increased conservation efforts that stemmed from basket weavers in the Western Ghats mountains. The report argued that exploitation of bamboo for paper was hurting the basket weavers’ economy and ability to survive.

Gadgil’s approach to environmentalism is one that stems from the pragmatic.

“You cannot take care of the environment without taking care of human concerns,” Gadgil said in his lecture, titled, “Science in the Service of a Symbiotic Society.” “Human beings are the only species that can act prudently, meaning that we are capable of thinking rationally about the long-term possibilities for our resources, and then acting on those thoughts. But most of the time we don’t do so.”

Gadgil believes in empowering the people who live off the land to govern it.

He pointed to Pachgaon, a rural village in the Haryana area of India. In 2006, the Indian Parliament passed the Forest Rights Act, which for the first time gave the people living in India’s forests agency over land management and conservation.

“Among the major sources of income in Pachgaon is the farming of tendu tree leaves, which can be used to roll beedis, or thin, Indian cigarettes,” Gadgil said. “However, the harvesting of the trees for the leaves ravages the plants, making it almost impossible for them to bear fruit.”

In the past the Forest Department would auction the right to harvest leaves to private traders who then paid villagers very low wages to perform the leaf collection. The new law allowed villagers to create their own rules governing how they would balance the economic and environmental concerns of the versatile crop.

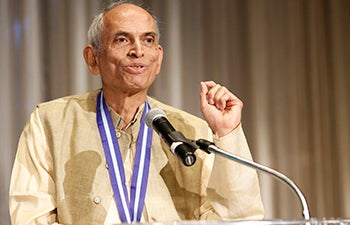

Madhav Gadil shares the 2015 Tyler Prize for his efforts to engage local people, as well as governments, in conservation policy.

“They decided that for two years nobody would collect the leaves and see what happened to the amount of fruit,” Gadgil said. “Within just two years, the fruit yield increased considerably, and their overall income increased as well.”

Gadgil ended his lecture with four actions people must take to balance the needs of our current livelihoods with those of the environment: evaluate systems of sustainable use and conservation of resources; organize participatory systems of monitoring resources; build locally specific, community-based forest management systems; and promote honest environmental impact assessments.

Lubchenco, who was recently named the first-ever U.S. Science Envoy for the Ocean by the United States Department of State, also spoke about the importance of enacting policy that will help restore balance between providing food and income for people now with ensuring resources are available in the future.

One policy Lubchenco described — the “catch share” or “rights-based approach to fisheries” model — aims to restore fisheries and improve ocean health. This new paradigm restricts who has access to specific fishing areas, how much time those permitted can spend on the water, and how much catch each can take.

“This idea changes the economic incentives for fishermen by giving them a stake in the future,” said Lubchenco, who was appointed administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere by President Barack Obama in 2008. “In fact, there are more than 200 rights-based fisheries in more than 40 countries.”

In the U.S., the number of rights-based plans has grown from six to 18. During that same time span, the number of overfished stocks has been reduced from 92 to 37, and the number of rebuilt fisheries has grown from zero to 37.

“Ending overfishing is possible,” Lubchenco said. “It may be difficult, but it is working.”

Reminding the audience to look toward a brighter future — rather than get bogged down in gloom and doom — Lubchenco compared efforts to address environmental challenges to an experience she had as a girl scout in the Colorado Rockies.

“I remember quite vividly one time, as we were trying to scale a really, really tall cliff, one of our leaders advised us that it was important to turn around every once in a while to see how far you had come to give you renewed energy and vigor to scale the rest,” she said.

“With that in mind, I think it is important for us to take stock of some of the amazingly good things that are happening in our progress to tackle some of these daunting environmental challenges.”

View a video featuring Tyler Prize co-recipient Jane Lubchenco >>

View a video featuring Tyler Prize co-recipient Madhav Gadgil >>