Nourishing the Soul

Drive through Echo Park and you can still see the original sign, faded now but still elegant, spelling out “Nayarit” in the slanting script of a bygone era. In its heyday in the 1950s, ’60s and early ’70s, people came from far and wide, eager to enjoy the authentic regional cuisine served at this popular neighborhood eatery, described by a Los Angeles Times restaurant critic as one of the best Mexican dining rooms he had ever visited.

But to its devoted patrons, this beloved restaurant was much more than a place to eat. For a quarter of a century, the Nayarit was a beacon of belonging and acceptance for those — many of them immigrants or members of the LGBTQ community — who struggled to meet these basic human needs in mid-century Los Angeles, where discrimination and segregation were rife.

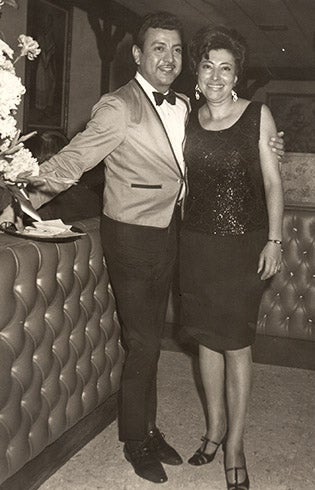

The Nayarit was founded in 1951 by Natalia Barraza, a Mexican immigrant and the grandmother of USC Dornsife’s Natalia Molina, Distinguished Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity and a 2020 MacArthur Fellow. Intrigued by her formidable ancestor, Molina plumbed her family’s history to understand Barraza’s story, and in the process illuminated many facets of the immigrant experience through the lens of her grandmother’s restaurant. Molina reveals her findings in a new book, A Place at the Nayarit: How a Mexican Restaurant Nourished a Community(University of California Press, 2022).

Cooking up the American dream

Barraza immigrated alone from Mexico to L.A. in 1921 at age 21. As she realized her own American dream, running a successful business — the Nayarit — and adopting two children, she also sponsored, housed and employed dozens of other Mexican immigrants, encouraging them to lay claim to a city long characterized by anti-Latino racism. Along the way, the Nayarit became a vibrant cultural space that embodied her vision of respect, community and mutual support, as well as an “urban anchor.”

Molina explains that urban anchors are usually considered to be civic projects, such as libraries or hospitals, but in our daily lives, the places where we feel seen, where we feel safe, are often places that we choose to go: bars, restaurants, cafes. These urban anchors, she says, are a different way to look at the city — not as a city planner envisioned it, but as immigrants finding their place in their new hometown.

“These are more than businesses,” Molina says. “They are sociocultural spaces, nourished by the countless small acts of everyday life that build and sustain affective relationships.”

The Nayarit was to become a prime example, providing a supportive “family” for immigrants and other marginalized people in L.A.

Nourishing the soul of an immigrant community

Molina notes that most Mexican restaurants of that period were called something more accessible, such as El Cholo or El Zarape.

“That my grandmother chose to name her restaurant for her home state of Nayarit signals to me that she had “patria chica” — literally, ‘love of a small country,’” Molina says.

It also created a beacon to others from that region. “When they wanted something familiar, they knew that regional food would really satiate not just their stomachs, but their souls,” she says.

In her book, Molina details her grandmother’s efforts to serve authentic regional food while still turning a profit.

“Sometimes she served much less expensive cuts of meat — pigs’ feet, organs. As the business developed and she had more money, she was able to offer whole fish when it was available. She would travel down to Tijuana for ingredients, like moles and chiles. She offered a taco enchilada combo and served freshly made flour tortillas, more associated with Northern Mexico, that became one of the restaurant’s claims to fame.”

“Anyone who was facing discrimination could go to the Nayarit and find acceptance.”

The restaurant was a place where you could go, not just to eat food from Nayarit, but to meet people from Nayarit, Mexico, Cuba and other parts of Latin America, and speak Spanish. It became an immigrant hub. And, Molina explains, because the food was so good and the atmosphere so lively, and because Echo Park was both a geographic and cultural crossroads, it drew people from all walks of life.

Musicians would go there after finishing their set, movie stars would eat there after a premier or a long day’s work, and Hollywood celebrities in mixed-race relationships would celebrate there because they felt accepted. When the L.A. Dodgers were in town, Latino baseball players would come to the Nayarit, as would Jaime Jarrín, the Spanish-language broadcaster for the team.

“Latino baseball players had money, but they wanted to go somewhere where they could feel comfortable, speak their language and not be discriminated against,” Molina says. “When I asked Señor Jarrín why he enjoyed going there, he said, ‘I wanted to see friends, bump into people I knew and speak Spanish.’

“Everybody that I interviewed, both in the U.S. and in Mexico, said that the Nayarit was the place to go,” Molina says. “And those that I interviewed in Mexico said, ‘If you visited L.A., but didn’t visit the Nayarit, it was like you hadn’t really visited L.A.’”

But in addition to the stars, the locals and the tourists, many others came to the Nayarit to find acceptance and a sense of belonging, among them immigrants and members of the LGBTQ community.

“Anyone who was facing discrimination could go to the Nayarit and find acceptance,” Molina says.

Making the invisible visible

So, how did Barraza establish the Nayarit as a place where marginalized people felt they belonged?

One way in which her grandmother achieved this, Molina says, is through her hiring practices.

“If she had just wanted to turn a profit, she could have focused on just hiring experienced Mexican wait staff, but she used the restaurant as a way to bring over family legally from Mexico by providing jobs and the necessary paperwork to obtain visas.”

Barraza was attentive to the needs of women, helping many single and divorced women immigrate. She also hired gay men and made them feel welcome.

As the book description says, “In a world that sought to reduce Mexican immigrants to invisible labor, the Nayarit was a place where people could become visible once again, where they could speak out, claim space and belong.”

Today, the Nayarit is long gone, yet its spirit lives on. Sold by Molina’s mother in 1976 after Barraza’s death in 1969, the space continued to operate as a Mexican restaurant until the turn of the century, when it was transformed into a very different urban anchor, The Echo — a music venue celebrated for its punk concerts, where another often-marginalized population finds acceptance. The Echo’s owners opted to leave the Nayarit’s iconic sign rather than put up their own. It still remains — a reminder to anyone seeking a home away from home, a place to be seen and a place to belong.