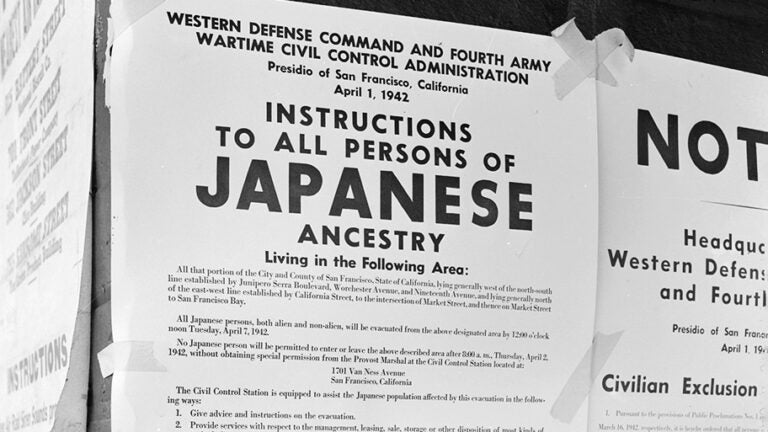

Japanese Americans exiled to prison camps 80 years ago by FDR’s Executive Order 9066

On Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. Though no reference to Japanese Americans appears in the order, an estimated 120,000 of them and their families — most of whom were citizens — were, in effect, incarcerated in detention centers across the western United States.

Experts from USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences discuss the mass incarceration with new insight into the factors that led to it, as well as examples of ongoing injustices that parallel the order.

An unforgettable injustice with legal aspects unresolved

Susan Kamei, managing director of USC Dornsife’s Spatial Sciences Institute and a lecturer in history, notes the tragic irony of the order.

“While President Franklin D. Roosevelt referred to Dec. 7, 1941, as a day of infamy, his issuance of Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, made that date a day of infamy, as well,” she said.

Kamei, the author of When Can We Go Back to America?: Voices of Japanese American Incarceration during WWII (Simon & Schuster, 2021), sees the date as a reminder of the importance of keeping prejudice at bay and liberty at the fore.

“Marking the 80th anniversary of the issuance of E.O. 9066 is our opportunity to better understand the dangers that result when impairing the civil liberties of marginalized populations under the guise of public protection, and to stand against those threats today.”

Kamei, an expert on the legal challenges that unfolded after the detention order, explained three court cases, including the landmark Korematsu v. United States that went to the U.S. Supreme Court.

She noted that Korematsu and others proved that they suffered a “manifest injustice” and were successful in having their criminal convictions vacated, but even so, those wartime Supreme Court decisions that bear their names have not been expressly overturned.

“Eighty years after the issuance of Executive Order 9066,” Kamei said, “the infamous legacy of the incarceration continues to be that our country presumed innocent persons, including American citizens, to be guilty of disloyalty to justify their long-term imprisonment simply because of their race, and serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of infringing upon the civil liberties of marginalized communities under the guise of protecting national security.”

An enduring disregard for human rights

Duncan Williams, professor of religion, American studies and ethnicity and East Asian languages and cultures at USC Dornsife, is the author of the award-winning American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War (Harvard University Press, 2019).

“As a presidential order, 9066 did not specify who the target was, it simply gave the U.S. Army latitude to round up anyone they deemed was a national security threat,” he said.

Williams notes obvious indications of racial prejudice during enforcement of the order.

“They took everybody from the West Coast — babies, grandmothers, even people of partial Japanese heritage, and put them into these camps,” he said. “We were also at war with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, but there was no mass roundup of all German Americans and Italian Americans.”

Williams also pointed to the egregious lack of due process, a key tenet of the Constitution.

“You’re normally afforded some judicial process before you’re put in a high barbed wire camp with armed guards, but this community was not afforded that protection. They weren’t told what crime they were supposed to have committed. They weren’t treated as individuals, but rather as a mass of unidentified people,” he said.

Williams sees the shadow of Executive Order 9066 looming over society today.

“Today, we have children being separated from their parents on the southern border, Muslims being banned from travel and the repetition of history as other groups are treated as undifferentiated enemies.”

The intergenerational trauma of an injustice

“Executive Order 9066 and its breach of principles of justice produced historically devastating effects,” said Dorinne Kondo, professor of American studies and ethnicity and anthropology.

Like Williams, Kondo voices concern about the continuing legacy of the order.

“We commemorate this event, but legally we can still incarcerate ‘undesirable’ others. My work as scholar-artist includes a play based on interviews with my parents, who were carted off to stockyards, then confined in camps in Tule Lake, California, and Heart Mountain, Wyoming. As a third-generation Japanese American who was born after the camps, I urge us to take seriously the affective consequences of such injustice. What are the reverberations of historical trauma across generations?

“Psychologically, politically, the past is not even past. ‘Internment’ is not over.”

A travesty at times ignored

William Deverell, professor of history, spatial sciences and environmental studies and director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West, expressed his own outrage at the injustices and called on citizens not to ignore the lessons of history.

“The internment of Japanese and Japanese American people, forcibly evicted from the West Coast, is a stain, a wrong, and a heartbreak. It is made all the worse by the stubbornness of our blind spots.

“‘It was a long time ago,’ some claim. It was not. It was a single lifetime ago.

“‘It was an aberration,’ some say. It was not. Rather, internment is a link in a chain made of anti-Asian thought and behavior running back and forth in time and place from 1942.

“‘I’d never heard of it,’ some say. Yes, you did. It is in the books; it is in the history classes. It is in the yearbooks of a school like USC: Here are the Japanese students in 1940 and 1941. Now it is 1942, where have they gone? You knew, you know, we all knew, we all know.

“The shame of it is that we forget over and over again. Memory and history are perhaps the only barrier we can construct to make sure it does not ever happen again.”