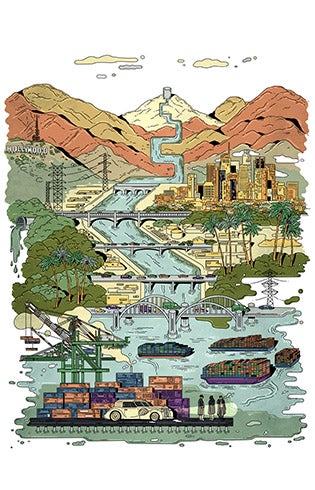

Dirty water: Los Angeles has a rich history of battles for control of the rivers, lakes and ocean around the city

In Los Angeles, the historians know the truth: The water here is anything but clean.

Like many areas with relatively high temperatures and paltry precipitation, water has always been a matter of life and death for L.A., a city that sits on a semi-arid coastal plain with desert on three sides and the Pacific Ocean on the fourth. The city resorted to drastic, at times deeply unethical — and occasionally even criminal — means to secure the vital resource that enabled it to grow into a major world metropolis.

“Water invites all kinds of shenanigans in the American West. It invites all kinds of deals: smoke-filled room deals, quiet deals, corrupt deals. And people need to know these histories,” says William Deverell, professor of history, spatial sciences and environmental studies at USC Dornsife.

The conflicts over water were waged on two fronts. There was the freshwater battle that involved, among other skirmishes, the struggle over procuring drinking water and irrigation. And there was the saltwater battle, involving the development of the Port of Los Angeles and control over its lucrative shipping and trade potential.

Dark harbor

If you watch enough television and movies, you might get the impression that nothing good ever happens down at the docks. Of course, that’s not true, but thanks to its depictions in popular culture, from On the Waterfront to The Wire, the American port has gained a reputation as a place associated with graft, dead bodies and illegally trafficked goods. And the Port of Los Angeles is no exception — from its origins as a site of some highly questionable land-grabbing to its lowest point in the 1960s, when bribery scandals and the mysterious death of its board president blackened its reputation.

The history of the port, located in San Pedro Bay, is the tale of a muddy tideflat that during the course of the 20th century grew to become the largest shipping container port in the Western Hemisphere. Alumna and former executive director of the port Geraldine Knatz chronicles the battle to control the waterfront in her book Port of Los Angeles: Conflict, Commerce, and the Fight for Control (Angel City Press and the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West, 2019).

“For L.A. to become an important city it needed a harbor, and so it was the water’s edge, what we call ‘the Tidelands,’ that was the focus of the struggle,” says Knatz, who holds a joint appointment as professor of the practice of policy and engineering at USC Sol Price School of Public Policy and USC Viterbi School of Engineering.

Knatz earned a master’s degree in environmental engineering from USC Viterbi in 1977 and a doctorate in biological sciences from USC Dornsife in 1979. Her book traces the port’s history, from the 1890s, when several railway barons saw its potential to yield lucrative freight shipping contracts, to its dominant role today. Dubbed “America’s Port,” the Port of Los Angeles now occupies 7,500 acres of land and water along 43 miles of waterfront.

In the late 19th century, Southern Pacific Railroad agreed to link L.A. to its transcontinental railway in exchange for a monopoly on transporting goods from the port to the city, a move that brought an influx of tourism and business to the fledgling town. But around the turn of the 20th century, a dispute arose as to whether the state of California had been authorized to sell the land around the harbor to private individuals and companies, including Southern Pacific. Thomas Gibbon, a member of the first Board of Harbor Commissioners for the port, argued it had not. He used his position — as well as his media muscle as publisher of the Los Angeles Daily Herald — to fight for the city’s right to reclaim the land in order to expand the port.

“The city of L.A. was aggressive, ruthless,” Knatz says. “They would blackball people who did business with the private property owners and tried to undermine those businesses because, from the city’s perspective, the property should be in public ownership. When it was privately owned, the city got no rent.”

After gaining control of the surrounding land, the city expanded the port to meet the needs of a growing nation. Although whispers of corruption and underhand dealings plagued its rise in the early 20th century, it was in the ’60s that the Port of Los Angeles “really hit rock bottom,” Knatz says.

“There was a scandal over leasing — without competitive bids — a large portion of the port’s Terminal Island for construction of a World Trade Center to a developer whose only assets were liens against his failed projects,” Knatz says. “Los Angeles Harbor commissioners were indicted, and in 1967, the Harbor Commission president was discovered floating facedown in the main channel. No evidence of foul play or suicide was found, however, and his death was ruled an accident.”

“The Tale of L.A. is also the tale of three rivers. the stories of these rivers — the Los Angeles, the Owens and the Colorado — are interwoven with the fabric of the city’s history.”

A tale of three rivers

If L.A.’s battles to control its waterfront were comparable to the plot of a noir movie, then so were the city’s legendary struggles to obtain sufficient freshwater to secure its expansion.

“The tale of L.A. is also the tale of three rivers,” says Deverell, director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West. “The stories of these rivers — the Los Angeles, the Owens and the Colorado — are interwoven with the fabric of the city’s history.”

The rivers also serve as a handy yardstick to measure the city’s expansion, Deverell notes. The Los Angeles River, the smallest, was adequate for a small pioneer town but quickly proved insufficient for the city’s aspirations.

“It supplied the city’s fresh water needs until about 1900, but it was a temperamental little river that was prone to flooding,” Deverell says. By the early 20th century, the city had decided to solve the problem by creating a concrete channel that whisked water from the mountains to the ocean as speedily as possible.

“We wouldn’t do that quite the same way today, because we’d be worried about sending all that water out to the ocean without trying to capture it. But back then they didn’t think that way,” Deverell says.

The Owens River powered the city’s rise in the early 20th century. The population of L.A. more than doubled in size from 1920–29, reaching 1.2 million by 1930. This dramatic population explosion prompted local officials to turn to another, larger source of water: the Colorado River. That aqueduct was completed in 1939.

“L.A.’s history with water is that of chasing a bigger river each time,” Deverell says. “The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which is dependent on the Colorado River, now has about 19 million customers. It’s an absolutely gargantuan water delivery, storage and distribution system.”

But it was the scurrilous behavior involved in the pillaging of the Owens River to feed the Los Angeles Aqueduct in the first decades of the 20th century that has been immortalized in film. It provided the inspiration for Roman Polanski’s 1974 neo-noir masterpiece Chinatown, acclaimed as one of the best films ever made about L.A.

“LOS ANGELES IS DYING OF THIRST!”

This doomsday warning is discovered by private eye Jake Gittes (played by Jack Nicholson) in an early scene in the movie, when he returns to his car after spying on Hollis Mulwray, the fictional chief engineer at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP), and finds a note tucked under his windshield wiper. It prophesizes drought and ruin for the citizens of the city.

A classic noir movie, Chinatown features all the usual suspects, including a femme fatale, as well as the familiar tropes of the genre: corruption, murder, a gumshoe and a dark secret. Though it is set in the 1930s (an artistic decision to showcase that era’s visually striking cars and clothing), the movie’s central theme has its roots in the real-life scandal that took place decades earlier when a rapidly expanding L.A. needed to secure more water to power its industries and provide for its burgeoning population.

“The conflict in the film, as in real life, is about water being taken away from the Owens Valley to be used in L.A.,” says University Professor Leo Braudy, Leo S. Bing Chair in English and American Literature.

As early as the late 19th century, L.A. was experiencing growing pains as it found its expansion hampered by a lack of water. In 1905, LADWP Chief Engineer William Mulholland, Mulwray’s real-life counterpart, oversaw the construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, which diverted water to L.A. from the Owens Valley, more than 190 miles north of the city.

The rights to the water and land in the valley had been acquired through some less than ethical maneuvers on the part of L.A. officials and other investors. The aqueduct, which was completed in 1913, ended up sucking the valley dry, devastating the lives of its residents, who were mostly farmers and ranchers. Yet the aqueduct project was expanded several times over the following decades.

“Basically, L.A. sticks a giant straw in the Owens River and sucks the water down to L.A.,” Deverell says. “Then it puts another straw in it, and another. The Owens Lake dries up, and not only have the people lost their water but the dust in the lake bed is kicked up and gets into the air, causing a lot of health problems for residents.”

The haves and the have-nots

In both L.A.’s saltwater and freshwater battles, the city’s politicians exhibited a ruthless single-mindedness that left many casualties in its wake — both human and environmental. In the early 20th century, the Owens Valley was transformed from fertile farming land into a parched, arid region where little would grow. Starved of water, local farms and ranches failed. Since the mid-20th century, air pollution from ships and cargo trucks has plagued neighborhoods around the Port of Los Angeles, with health consequences for local residents and workers.

An early scene in Chinatown warns of the humanitarian costs, showing L.A. officials gathered at a town hall meeting to discuss a water project. An angry farmer walks down the center aisle with his sheep, yelling at the bureaucrats that he no longer has enough water for his livestock and asking what they plan to do to help him. He is quickly shooed out of the building.

“Owens Valley is a situation where big, brawny L.A. decided they would push around a small community,” Deverell says. “And before L.A. came, white Americans had seized the land from the Paiute Indians. So, there’s this recurring story of the powerful snatching up water resources.”

Braudy, professor of English and art history, agrees, noting that L.A.’s so-called “Water Wars” illustrate the city’s loss of innocence, foreshadowing its rapid rise to become a major metropolis with all the power, corruption and lies that entailed.

He points to one particularly symbolic scene in Chinatown that encapsulates the growing divisions in class and privilege in the city. After the disrupted town hall meeting during which the embattled farmer’s pleas for water for his livestock are dismissed, Gittes drives to Mulwray’s house in Pasadena. The shot pans out as his car enters the long driveway, flanked on either side by a carpet of bright green grass. Gittes walks past a man hosing down one of Mulwray’s cars to reach the backyard, where well-tended plants and trees surround a rock pool with a running waterfall.

“We need to grapple with the fact that water is obviously critical to our survival, but it invites people who want to monopolize water resources,” Deverell says. “We have to make sure that the decisions we make about water in the 21st century are as democratically derived as possible. We’ve got to push water out of its dark past in L.A. and into the sunshine.”