Course is Work of Art

When Rocio Peña-Martinez walked into the David Zwirner Gallery in Chelsea on Manhattan’s Westside, her eyes followed the hand-blown, blue glass balls.

Each ball balanced atop white plastic casts of classical Roman statues or a boy in a hat sitting cross-legged or a snowman. Most famous for his reproductions of innocuous objects made monumental — balloon animals and the like, produced in mirrored stainless steel — artist Jeff Koons’ exhibit Gazing Ball resonated with Peña-Martinez.

Admiring each sculpture, the ball seemed to dare her to stare into it. When she did, her own image stared back. Gazing into the orb, she could see the whole exhibition with all the people mulling about.

“Each individual sculpture falls out of focus as the entire layout of the three connected exhibition rooms is reflected in the shiny spheres,” Peña-Martinez said. “Each work and its own ‘blinking, blue eye’ seem to radiate. The human observers become part of the work. You take everything in at once, so the ball and the audience fall into the body of great classical sculpture.”

An anthropology and neuroscience major, and art history minor at USC Dornsife, Peña-Martinez was in a perfect position to discuss the myriad observations she had after experiencing the exhibition. She was in Chelsea during a Maymester course, “Contemporary Art in New York,” taught by Suzanne Hudson, assistant professor of art history at USC Dornsife.

During group discussions, Peña-Martinez aired some burning questions: With the electric blue balls, the artist was inserting himself into each sculpture — why? A viewer was forced to consider his or her own reflection and the artist at once. The omnipresence of Koons in all aspects of his work means the humor is not lost,” Peña-Martinez eventually concluded.

This is one of many discussions that took place May 20 to June 15, when undergraduates throughout the university viewed numerous exhibitions and installations in museums, galleries and outdoor sites.

During the course, they studied the history of criticism with the goal of learning to closely examine and then critique artwork. These are skills necessary for this genre but fundamental to the discipline of art history more broadly, Hudson said.

Students participated in seminars three afternoons a week for three hours. The seminars introduced students to the history and practice of writing about contemporary art. Beginning with historical criticism, students then investigated more recent discourses around modern art. They also analyzed contemporary criticism’s numerous venues such as newspapers, magazines, monographs and online formats.

The undergraduates generated their own writings based on responses to objects and exhibitions they visited as a group. By the end of the course, each student had a portfolio of critical writing, which Hudson and the other students helped to edit.

“Writing is a process, and editing is integral to the process,” said Hudson, a longtime critic for Artforum, the preeminent publication on contemporary art.

During the trip, meetings with art professionals — from critics and editors to curators and educators — offered a range of opinions that informed group discussions and provided insights into what these kinds of jobs entail.

Hudson wanted the course to emphasize the value of critical thinking and effective communication. She also wanted to show students what can be done with a degree in art history.

“A museum curator is an obvious career, if a difficult one,” Hudson said. “But many of my students didn’t have a sense of the different possibilities beyond that: the competences other art careers require, the needs they meet for different publics and the opportunities they afford.”

For example, working in a museum extends far beyond overseeing the institution’s collection. There is an educational component. Inside museums, Hudson had the undergraduates study the wall labels that tell the story of each collection. She had them consider the content in the audio provided during tours. And she asked them to consider factors of installation, meaning how the works are placed within a room, or an exhibition.

She introduced them to Christa Blatchford, deputy director of the nonprofit Joan Mitchell Foundation, which expands the mission of abstract expressionist artist Mitchell to support the development of diverse contemporary artists. Among others, Hudson’s students met with Domenick Ammirati, senior editor at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and Andrea Scott, art critic at The New Yorker. Dana Miller, curator of the permanent collection at the Whitney Museum of American Art, led a private, after-hours tour of her Jay DeFeo exhibition.

“My students were hungry for the knowledge that all of these people were providing,” Hudson said. “This trip exceeded my expectations.”

Hudson noted that the trip opened up possibilities for Tanya Mashian, who is majoring in accounting, but has a deep interest in art.

“She asked, ‘is there an industry where I can do accounting and love what’s going on around me?’ ” recalled Hudson, who emphasized the business side of museums, galleries and foundations to Mashian.

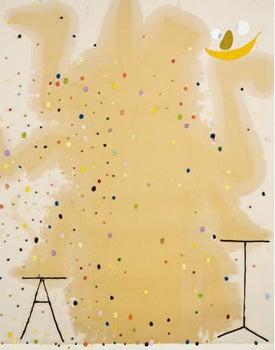

Art history major Julia Riley was thrilled to meet Florian Meisenberg, a Berlin-born artist who personally gave students a tour of his show at the Simone Subal Gallery on the Lower East Side in Manhattan. When Riley chose to write a review of this work, she had to think about the implications of having heard the artist put forth his intentions, and decide how she would weigh that information relative to her own observations about their materials and meanings.

Meisenberg’s oil paintings employ linseed oil on unprepared raw canvasses. During the creative process, the oil soaks into the canvas, leaving behind what appears to be sporadic stains, Riley noted.

“The application of oil onto canvas is minimalistic and restrained,” Riley wrote in her review. “Meisenberg asks his audience to take from his works more than a visual representation of a figure, but an understanding of an art form that can transcend the need for paint, yet relies on paint application to create his canvas pieces.

“The rawness of his works, with their unframed edges and places of untouched canvas, speaks to the artist’s consciousness of his medium and his effort to preserve its purity.”

Riley said the course gave her the courage to switch from plans to attend law school to pursuing a career in art business.

“The unknown can be the scariest part of entering the job market, but after learning so much more about the options out there, I am confident I can go for a career in something I have always loved,” Riley said. “This trip to New York City really opened my eyes to so many potential career options for someone with a passion for art.”

Other students also responded to the course enthusiastically. In critiques, one wrote:

“This course taught me more than all of my other courses combined. I had an amazing time in New York, learning and exploring the city. This was my favorite part of my four years at USC. I would recommend it with no reservations.”

Another called it an invaluable experience.

“The contacts and networking alone were invaluable, and the professor’s candid depiction of art writing in the real world made this a crucial step in my path to being an arts journalist.”

Yet another now felt equipped to enter the job market as an art history major.

“Professor Hudson showed us useful job opportunities, and taught us how to think deeper and write clearly. She provided me with the most valuable learning experience I have ever had.”