Course teaches students how to master chess so they can master their minds

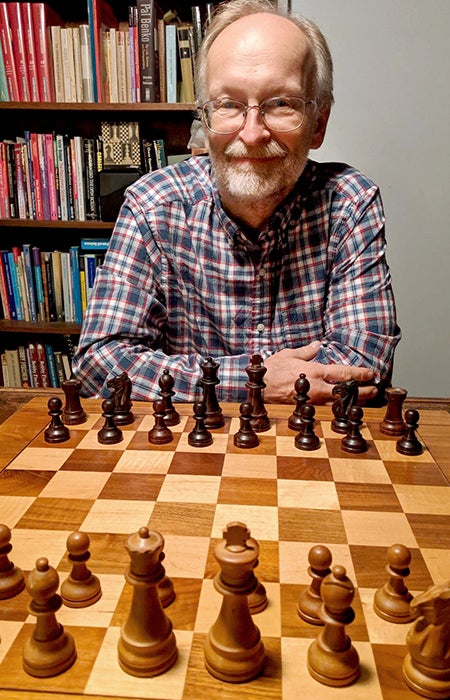

Stroll around the USC campus on a clear day and you might run into Jack Peters, lecturer in Slavic languages and literature, playing a dozen chess matches simultaneously beneath the Tommy Trojan statue.

Once a term, Peters sets up an array of checkered boards and invites passing students to a game. Moving swiftly between opponents, taking only seconds for each move, he often completes 50 games in a couple of hours.

You’d imagine Peters’ brain to be on the verge of shorting out by the end of it all, but he admits the challenge is mostly physical. “I move really quickly, and it’s usually hot, so I get pretty tired walking around for hours,” he says.

That’s because chess allegro is all in a day’s work for Peters. He’s been an International Master since 1979, a lifetime title of distinction awarded to world-class players, and has squared up against greats like Mikhail Tal, the eighth person to hold the title of World Chess Champion.

Peters was chess columnist for the Los Angeles Times and has published multiple books on the game. He’s taught the class “Chess and Critical Thinking” at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences since 2002, guiding hundreds of students into the game that he has played since he was 8 years old.

A mind game

To Peters, there’s much to learn from chess besides how to best your opponent. Mastering chess is a means to master critical, tactical thinking, which can be applied almost universally to life’s big challenges.

“Students have to first recognize the situation they are in and then set priorities: What are the important features here?” says Peters. Constant adaptation is also key. “One of the hardest parts about chess is that you might have a great idea, but your opponent might also have their own idea, and then the plans change.”

Such skills are also attractive to employers — the ability to plan, solve problems and analyze information are frequently cited as some of the top desirable traits in recruits.

For the final exam, Peters sets up about 20 boards in his classroom and plays every student at the same time. He doesn’t often get bested. “Maybe once a year or so I have someone that beats me,” he says.

Losing to the professor isn’t a problem in Peters class, however. “Their final isn’t about winning. They write about the game we played, describe their strategy and any mistakes they made. They’re graded on how well they understand what happened and the principles of the game.”

To Peters, the lesson he wants students to learn isn’t one of victory but how critical thinking, careful strategy and learning from one’s mistakes can better you for the next challenge.

Chess plays a historical role

It’s not just for sharpening the mind, however. Peters’ class touches on a little of everything, from art to science to business. A particular focus is the way chess became intertwined with both Russian cultural identity and Soviet strategy abroad.

After the game’s invention in India around 530 A.D., traders spread chess into Russia where it became a popular pastime for noble and commoner alike. Ivan the Terrible, ruler of Moscow from 1533 to 1547, was an avid player and earned his name in part for killing an opponent with a chessboard during a game.

After the Russian Revolution in the early 20th century, Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin hoped to empower a demoralized populace by producing a great generation of chess players. The USSR established the Soviet Chess Federation to train children starting at the age of 5 to become formidable players.

Lenin’s successor, Joseph Stalin, continued Lenin’s efforts, placing Nikolai Krylenko, public face of the ruthless Soviet justice system, at the head of the organization. “Krylenko saw chess as a propaganda opportunity,” explains Peters. Skilled players could demonstrate Russian intellectual might on the world stage.

Chess became so synonymous with USSR prowess that a 1972 match between world champion Boris Spassky and upstart American Bobby Fischer turned into a heated, symbolic showdown between world powers poised at the knife’s edge of battle.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1990, chess reverted to something of a Russian export. “Over the next 10 years, many of the grandmasters raised in the Soviet Union actually became citizens in other countries and started playing for those national teams.One of the jokes at the chess Olympics was ‘our Russians can beat your Russians,’ as every team would have one or two Russians who emigrated,” recalls Peters.

Despite this history, chess is actually an immensely diplomatic game, Peters reminds us. “As long as both players know the rules, no common language is needed to play chess.”

Keep calm and play on

Despite the mental rigor chess demands, Peters’ class is a popular one. Vespera Luo, who is majoring in chemistry at USC Dornsife and journalism at USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, enrolled after seeing recommendations for the class on the USC Reddit forum, and members of USC’s chess team sometimes pop by for a game or to recruit new players.

It’s enduring popularity likely has to do with Peters calm, expert approach. “Mr. Peters is so patient with a beginner, he doesn’t feed you answers but leads you to the right path of thinking,” says Luo.

It’s also a rare opportunity for chess enthusiasts to try their hand against an expert. “I really enjoyed playing against Jack and seeing in person how good someone can be at chess,” says Tristan Tausch, a business administration major at USC Marshall School of Business.

For Luo, lessons from the class extend to the meditative as well, referencing a memorable anecdote from Peters. While working for the L.A. Times, Peters found himself hastily writing an article on the infamous match between Russian chess master Gerry Kasparov and IBM’s computer Deep Blue. (Kasparov was defeated, marking a shift in humankind’s perceived mental power over machine.)

“Mr. Peters said it was the first time his editor rushed him to write something because ‘there are no emergencies in the chess world.’ I remember him saying this sentence, and it just struck me somehow,” says Luo. “We’re living in such a fast-paced world today, and at that moment I realized I prefer some quietness and slowness in my life.”

7/18/24: This story was updated to remove outdated references to the COVID-19 pandemic.