Brainwaves by the Sea

Every student knows how vitally important it is to remember information for a final exam. However, trying to memorize your class notes in the library can be challenging. Distractions — the person next to you whispering to a friend, the ring of a cell phone — can make focusing difficult.

In today’s world, when our senses are constantly bombarded with information, it is critical to prioritize information. This selectivity is heightened when we factor in the danger of threats or mental challenges, thereby enhancing our ability to remember events relevant to our well-being.

The excitement of a reward can also affect memory.

“We know first-hand that motivational incentives, such as the reward of a chocolate bar or the punishment of missing a party, can promote effective learning,” said David Clewett, a USC Dornsife doctoral student in neuroscience. “This process appears to be driven by an increase in arousal, which improves our ability to focus on the things we care about. Since mental resources are limited, an extra boost of arousal helps ensure that valuable information is even more likely to be remembered, while distractions are even more likely to be forgotten.”

As a participant in USC Dornsife 2020’s Graduate Summer Fellowship Program in Social Neuroscience, Clewett’s project demonstrated that providing monetary incentives, in which money was given or taken away according to performance, was a highly effective way to enhance memory for important information while suppressing it for distractions. This phenomenon is known as Arousal-Biased Competition (ABC).

“Our brain performs this process seamlessly,” Clewett said, “yet the neural mechanism underlying ABC isn’t fully understood.”

Previous research has linked arousal in the brain, such as that caused by monetary gains or losses, to norepinephrine — the brain’s version of adrenaline — suggesting that this stress hormone is centrally involved in ABC memory effects. Clewett is examining whether blocking norepinephrine will diminish the beneficial ABC memory effects resulting from an incentive such as money.

“Highly arousing events form our most vivid memories. Thus, I’m interested in knowing whether motivational incentives can be used to extend this memory benefit to other important – yet intrinsically non-arousing – information,” he said.

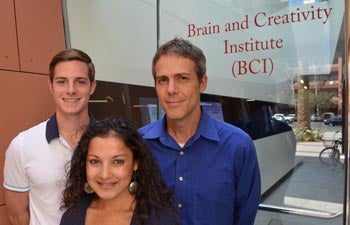

John Monterosso, associate professor of psychology (right), with David Clewett and Vanessa Singh, two doctoral students who participated in the Dornsife 2020 program. Photo by Erica Christianson.

Clewett was among 10 USC Dornsife doctoral students enrolled in the program who presented their summer research projects to peers and faculty during a weekend conference at the USC Wrigley Marine Science Center on Catalina Island.

The Ph.D. students in neuroscience, psychology and economics were joined by six faculty members from August 24-25. The group explored the fertile ground created by the program’s collaboration among several departments and centers within USC Dornsife — including psychology, economics, the neuroscience graduate program, the USC Brain and Creativity Institute (BCI) — and also USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and USC Rossier School of Education.

“Our goal is to stimulate and support doctoral students’ work on projects that combine neuroscience with other disciplines,” said John Monterosso, associate professor of psychology at USC Dornsife. Monterosso leads the program with Wendy Wood, Provost Professor of Psychology and Business and vice dean for social sciences.

“We want to help train scientists who will leave USC with the tools and techniques they need to investigate human behavior across multiple levels of analysis,” Monterosso said.

Clewett was drawn to the program for the collaboration opportunities with researchers from other fields, including education and economics.

“I was fortunate to participate in the program last summer, so I was eager to return to Catalina to hear about other students’ projects, ranging from decision-making to mindful meditation,” he said. “The field of neuroscience is interdisciplinary by nature, so it’s exciting to take advantage of others’ expertise to enhance my own research.”

Clewett said the program served to remind him of the bigger picture — something he found helpful due to the increasingly specialized nature of his research.

“The program helped me focus on the broader impact of my research and how it advances our understanding of incentive-based learning, the reliability of eyewitness testimony, and arousal-related pathology such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,” he said.

Vanessa Singh, a Ph.D. student in psychology, presented her research on why schizophrenics in developing countries tend to display milder symptoms than those in developed countries. She is investigating whether a family environment that places greater emphasis on social awareness may play a role in reducing the disability associated with the disorder.

“Very little research has been done on how social factors may influence the neural, clinical and social functioning of persons with schizophrenia,” Singh said. “Our study aims to broaden the range of social factors we take into account when we consider the possible causes of the disorder.”

“Specifically, we argue that the type of interaction patients have with their families and caregivers, as well as the social attitudes of their culture, are likely to influence brain functioning in significant ways that could serve to either diminish or worsen symptoms and impaired social functioning.”

Vanessa Singh, Ph.D. student in psychology, presents her research examining how social factors influence brain functioning in schizophrenia during the Catalina Island retreat. Photo courtesy of John Monterosso.

Patients with schizophrenia show evidence of hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity in the default mode network — the regions of the brain that are engaged during introspection, daydreaming and emotion processing. This is linked to the fact that patients diagnosed with schizophrenia are more focused on their own thoughts and feelings than typical people.

While the brains of people with normal mental health are able to switch easily back and forth between activity in the default networks and networks of the brain dealing with external tasks and stimuli, this is not the case for brains of schizophrenic patients, she said.

Working at USC Dornsife’s BCI, Singh used a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner to study neural activity and connectivity in schizophrenic patients.

In Singh’s study, patients’ neural activity was monitored as they watched videos showing someone getting physically hurt, for instance by falling off their bicycle, and another person experiencing deep emotional pain, such as that caused by the death of a loved one.

Watching the videos required patients to switch back and forth between different neural networks. One required the viewer to focus on compassion induced by a sudden, but relatively simple, external event (falling). The latter demanded the more complex processing of empathizing with emotional suffering (bereavement), which requires the patient engage in introspection.

“Our findings supported our hypotheses that in a resting state, schizophrenic patients show greater connectivity of the brain’s default [introspection, daydreaming] network compared to healthy controls,” Singh said. “These patients had poorer performance on tasks that required them to switch back and forth between the simple, external activity like falling and the internally directed mental processing required to process bereavement.”

Singh will now correlate her findings with each patient’s socialization characteristics.

“These findings raise the possibility that a family environment that stresses the importance of others’ needs may lessen psychosis by encouraging neural flexibility between focusing on an external task and introspection,” she said.

Singh appreciated the cross-disciplinary input offered by the program.

“Questions and comments from faculty and students belonging to fields other than my own gave me a new perspective of looking at my research, raising new questions and offering new interpretations for results and novel methods of analysis,” she said.

Doctoral student Brad Gasser presents his computational modeling work on primate communication at the Dornsife 2020 retreat. Photo courtesy of John Monterosso.

The program is part of USC Dornsife 2020, which encourages faculty to work across existing departments and programs to identify a set of themes that will be of great societal relevance and importance in years to come. Their initiative is called, “Adapting to Downturn, Rising with Recovery.”

Students in the program initially formulated their projects in April and were paired with two faculty mentors from different departments to help give them various perspectives on their work. In its second year, the summer program continues to be a great success.

“We had a terrific set of talks at Catalina and the students really got a lot out of presenting their work to their peers and to faculty,” Monterosso said. “The best moments were when speakers were asked questions or given comments that would not have come from their home discipline. I think that was valuable for the students — to be forced to come at their scientific question from a different direction.”

The weekend was not all work and no play, however. Participants were able to enjoy kayaking and stargazing during their visit to the scenic island. “The night sky from the island is spectacular,” Monterosso said. “We all got a chance to see Saturn through a telescope, and some of us caught glimpses of shooting stars. It was inspiring.”