Memento Mori

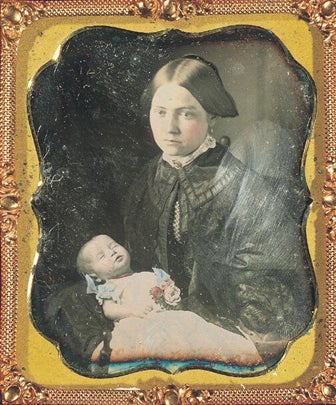

In its ornate, gold frame, the 19th-century photograph shows an infant cradled in its mother’s arms, its eyes closed, its lips slightly parted. The mother’s cheeks blush rose beneath the smooth, dark wing of her hair. Clothed in gauzy white muslin embellished with lace and blue ribbons, a coral necklace at its throat, the cherished child clasps pink and cream flowers in a tiny fist. The infant’s summery clothes contrast with the heavy, shapeless black cape that envelops the mother, who gazes, not affectionately at her child or even shyly at the photographer, but out and down into space, her deep, empty eyes expressionless.

“Look at her shock,” said William Deverell, professor of history at USC Dornsife and director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West. “A very young mother, but that child is no longer alive.

“When I show a post-mortem photograph of a child in the arms of its mother, my students hesitate because they of course want to think that baby is sleeping, but if they look closer, they begin to notice that something is not quite right,” he said. Deverell teaches the popular 19th-century practice as part of his undergraduate course “History of American Childhood.”

“Undergraduates are initially shocked that the mother would hold the dead child in such a loving embrace, but once we discuss it, it begins to make sense for them,” he said.

Post-mortem photography often represented the only image of that human being ever taken, he explained. This was especially true for infants and young children.

“The child had to hold still for too long for parents to be willing to purchase expensive portraits of their children when they were very young,” Deverell added. “But if the child died, there was often a desire to commemorate his or her life, or even death, by having a photograph taken.”

As the only visual remembrance of the deceased, post-mortem photographs helped families grieve and were considered among a family’s most precious possessions.

An intimate familiarity with death

A post-mortem photograph of a grieving mother with her deceased child, taken circa 1850. Image courtesy of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West.

“We always associate the Victorians with morbid, dark, weird attachments to death,” said Lindsay O’Neill, assistant professor (teaching) of history. “But it’s not just that the Victorians were morbid people, it’s that their key values are tied up with new conceptions of death that emerged in the 19th century.”

The Victorians’ intimate relationship with death is almost unthinkable to people today.

“For us, the idea of laying out a corpse, attending a wake or seeing a dead body is traumatic,” said O’Neill, a specialist in British history. “We just don’t want to think about it.”

In the 19th century, people had no choice. Death was an ever-present reality. Death rates soared as a result of increased urbanization brought about by industrialization. Working-class parents could expect to lose one in two children at a young age, while middle- and upper-class families lost on average one in five.

“On any stroll through a 19th-century cemetery, we would be shocked at the number of gravestones marked ‘baby,’ ‘infant’ or ‘child,’ ” Deverell said.

What’s astonishing to modern eyes is that these children were buried unnamed. It was not uncommon in the American past, Deverell explained, for parents not to name a child until it had safely passed through a predetermined ‘seasoning period’ of up to four years, lest they attach personality and personhood to that child. Until then it would simply be called sister, brother, baby. If a named child died, that name might be given to the next sibling born of the same gender.

“There’s a fluidity with the personhood of that child, but an attachment to the name,” Deverell explained. “If you poke at that, it shows a tragic familiarity with death.”

O’Neill suggests that what we find morbid today in Victorian attitudes toward death originates from this very familiarity, the acceptance of mortality and the comfort found in keeping the dead within the family fold.

“Because family is so important to the Victorians, they want to include the dead among the living,” O’Neill said. “This translates into wakes held in the parlor while children play around the corpse, picnicking with deceased relatives in the family crypt and wearing locks of [the deceased’s] hair in lockets or brooches.”

Complex mourning rituals

Death rituals previously reserved for the upper classes developed into a complex and widely adopted series of mourning rituals. This highly choreographed set of protocols included lengthy prescribed mourning periods that required widows to wear black for a year and a day while men pinned black ribbons to their clothing. Black-edged mourning stationery was used for correspondence, and tresses of the deceased’s hair, sometimes twisted and teased into elaborate sculptures, were framed and displayed in drawing rooms, alongside death masks — wax or plaster impressions of their faces made after death.

Opulent funerals featuring elaborate processions, ideally led by a glass carriage bearing the coffin and drawn by prancing black stallions, their heads adorned with black ostrich feathers, became de rigueur. The more ostentatious the funeral, the more it proclaimed the wealth and status of the bereaved. The poor, for their part, joined burial clubs, allowing them to buy their own funerals on layaway for a few pennies each week.

Undertakers flourished during the Victorian era and death became a business, professionalized and commodified as never before. This was manifested by the shift away from old churchyards, viewed as dangerously unsanitary, to the new “garden cemeteries.” These commercial enterprises began opening in semi-rural suburbs in the first half of the 19th century in response to mounting concerns over public health. Victorians erroneously blamed what they called “miasma” — a pestilent stench they associated with decomposing bodies piling up in the old, overcrowded churchyards — for causing epidemics that killed tens of thousands of people in the newly congested cities of the Industrial Revolution.

“Because family is so important to the Victorians, they want to include the dead among the living.”“A big fear during London’s 1854 cholera epidemic was that plague bodies had been uncovered,” O’Neill said. “In Britain there is connection to past moments of death because churchyards are filled with graves dating back to the 14th and 15th centuries, many holding victims of the plague.”

The most famous of the new Victorian garden cemeteries was London’s Highgate — the final resting place of Karl Marx, novelist George Eliot, scientist Michael Faraday and Elizabeth “Lizzie” Siddal, the Pre-Raphaelite muse and wife of artist and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Grief-stricken by his young wife’s untimely demise, Rossetti slipped the only manuscript of his poems into her coffin before burial. Seven years later, in 1869, he had her coffin exhumed under cover of darkness so he might publish them. Witnesses reported that the luxuriant auburn locks for which Siddal had been celebrated in life had continued growing in death, so when the coffin was prized open, it was found to be filled with her coppery hair. Rossetti retrieved his poems, although legend has it a worm had burrowed through them, leaving many illegible.

“There are plenty of cases in the 19th century of people, who for reasons generally tied to love and not a weird eeriness, dug up the dead,” Deverell said. “Ralph Waldo Emerson famously opened up his wife’s coffin because he missed her so.”

Using corpses to interpret a glorified past

Thea Tomaini’s new book, The Corpse as Text: Disinterment and Antiquarian Enquiry, 1700-1900 (Boydell Press, 2017), explores the two centuries-long vogue for digging up important historical figures to “read” their corpses, as though they were documents describing an idealized past. By “interpreting” the corpses of the historically dead, antiquarians attempted to validate English nationalist ideals and to establish the past as a Golden Age of unimpeachable superiority.

“What’s fascinating about this is that a person of historical importance — be they literary, royal, a member of the church, a politician, or a national hero — remains almost as important in death as in life,” said Tomaini, professor (teaching) of English. “There is a continued relevance, not only for the dead, but for the actual corpse.”

In her book, Tomaini illustrates how “reading” corpses was used to support political argument by chronicling the disinterment of Charles I, the Catholic Stuart king executed for high treason by Oliver Cromwell in 1649.

Hastily buried in secret in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, to prevent royalists from stealing relics and Cromwell’s supporters from vandalizing the tomb, Charles’ final resting place was soon forgotten.

“Ten years after Charles’ death, among the handful of people who knew his burial place, several had died and the others couldn’t recollect where they had put him,” Tomaini said. “They knew he was under the nave somewhere, but they’d forgotten exactly where. It wasn’t until 1813 that his body was accidentally discovered by workmen.”

Amid great excitement, the great and good, including King George IV, the Prince Regent and their personal physician, gathered for the opening of Charles’ coffin. Much to everyone’s satisfaction, he was found to be in tremendously good condition.

“His skin was supple, and he looked very good,” Tomaini recounts. “They brought the head up out of the coffin, noting that it had been sutured back on to the body with black silk thread and the mark covered with a black velvet ribbon. And they picked up the head and passed it around and all agreed that it was him and that the majesty was still clear on the king’s face.”

This was immediately politicized to validate the monarchist argument that royalty was ultimately unassailable.

With King Henry VIII, whose burial place — also forgotten — was discovered next to Charles, it was a different story. Inside Henry’s outsized coffin, nothing remained of the larger-than-life monarch, notorious for his excessive and often violent appetites, but a tiny shriveled skeleton and a few tufts of ginger beard. His less-than-imposing remains were interpreted as a sign that tyrants never win — even in death.

Danse macabre

Art executed in the vanitas style incorporates symbols of mortality, thereby reminding viewers of life’s transience.

For centuries, cemeteries served as a powerful reminder of the importance of living a morally righteous life. Deverell notes that in the 17th and early 18th centuries, Puritan parents frightened young children into righteousness by urging them to walk through graveyards, past tombstones carved with skulls and crossbones, to make them understand that death, their inevitable companion, was stalking them.

In 15th-century Europe, even more explicit memento mori (reminders of death), or cadaver tombs, featured transi sculptures showing the body in an advanced state of decomposition, often complete with worms or other flesh-eating creatures.

Nor were memento mori limited to cemeteries. Another example, the danse macabre, shows a dancing grim reaper carrying off rich and poor alike. Chapels constructed from bones, such as the 16th-century Capela dos Ossos in Evora, Portugal, inscribed with the words, “We bones, lying here bare, await yours,” served as a silent reminder of mortality. Paintings executed in the vanitas style featured symbols of mortality such as skulls or, more subtly, a flower losing its petals and were meant to remind viewers of the transience of life, the futility of pleasure, and the certainty of death. Public clocks often bore such cheery inscriptions as ultima forsan (perhaps the last [hour]), while people carried smaller, portable reminders of their own mortality. Mary Queen of Scots owned a large watch carved in the form of a silver skull, which counted down the minutes until her beheading on Feb. 8, 1587.

The gentle goodnight

Victorian cemeteries, however, were less about morbid reminders of mortality and more about reunions, O’Neill notes.

While we might find it slightly macabre to take a Sunday walk, much less stop for a picnic, in a graveyard, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, American cemeteries were regarded as parks, places to relax and repose in nature.

In Britain, a similar story unfolded. At Highgate, families — children included — dressed in their Sunday best to take tea with their dear departed in the family crypt.

“Victorians start to emphasize less the previous personal battle for the soul and more the loss of a cherished individual to the family unit,” O’Neill said. Heaven for Victorians no longer represented only the place where they would be united with God, but also the place where they would be reunited with their family after death. Victorians found comfort in the idea of having a crypt where their family would visit them, thus perpetuating beyond the grave that sense of inclusion and continuity that the family personified to them so strongly.

As the connection with the church lessened, paintings of the period depicting death scenes showed doctors and families in attendance, rather than priests.

“A strange separation of death and church is taking place, and what replaces church is family,” O’Neill said. “Victorians aren’t becoming less religious, but the nature of their religion is changing. … The vengeful God of previous centuries is replaced by a more forgiving God and death is sentimentalized as a smooth, sweet passage, a homecoming.”

Highly valued, this idealized concept of a “good death” meant dying peacefully surrounded by family and friends, with time to say goodbye and doctors in attendance to ease any pain. It was a time of acceptance, family bonding and meaningful last words. Unexpected, messy and uncontrollable, cholera represented the worst kind of death to Victorians, while tuberculosis, a wasting disease to which many young Victorian women succumbed, offered the possibility of an idealized, lingering demise. Romanticized by Victorians as “angels of the home,” such young women embodied the perfect death.

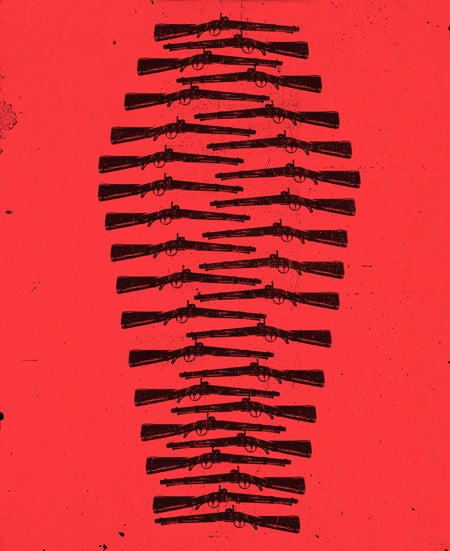

Such gentle ideas about peaceful death were shared in the U.S. until they were savagely disrupted by the Civil War. More than 700,000 Americans lost their lives, raising the question of how to deal with death on such a massive scale.

More than 700,000 Americans perished in the Civil War, transforming the nation’s experience of death.

“[The war] helped drive home this tragic, romantic notion of the good death, a brave death, a resigned death, a religious death, a poignant death, all wrapped up into notions of nobility, chivalric masculinity, patriotism, and filial loyalty to one’s parents, as soldiers die with the names of their mother and father on their lips, or a picture of their children pinned to their chest,” Deverell said.

As Americans struggled to cope with traumatic death stripped of all desired aspects of parlor comfort, they nevertheless clung to the idea of the idealized death, striving to stage it wherever possible, even in Civil War hospitals. There, nurses — among them poet Walt Whitman, whose Civil War nursing diaries are preserved at the Huntington Library — play a critical role in recreating this almost romantic view of death, of being present at the moment of passing, of tenderness, the kiss on the cheek and the gentle goodbye.

Embalming Lincoln

If any single death can be considered to have most deeply affected Americans’ view of mortality, it is the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln in 1865.

“Regarded both as a sacrificial Christian martyr and a republican hero who gave his life for the people, Lincoln came to stand for all of the dead of the Civil War,” said Richard Fox, professor of history and author of Lincoln’s Body (W.W. Norton & Company, 2015). “Americans identified personally with his death as if he were a family member, sometimes even leaving a symbolic empty chair at the dinner table they called ‘Lincoln’s place.’ ”

In response to public demand, the funeral train bearing Lincoln’s body traveled 1,654 miles, through seven states and 180 cities from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Ill. Twelve cities held public viewings of his body.

“It’s estimated that a million people saw his body and another six million saw the train — more than a quarter of the Northern population,” Fox said. “Even in cities that only obtained a stop in the middle of the night, thousands turned out, dressed in their Sunday best, while women decorated the train with garlands of flowers to show their respect.”

All this was made possible by the embalming of Lincoln’s body. This process — brought from France — became popular during the Civil War because it allowed grieving families to bring the bodies of their fallen sons home to recreate the idealized deathbed experience.

“In Lincoln’s case, it didn’t work out as perfectly as the embalmers predicted because his body was jostled too much and too much dust descended upon it during the trip,” Fox said. “But, for two weeks it looked very presentable. Only in the third week did it start to turn in ways that were unpleasant for viewers.”

By the turn of the 20th century, embalming was so popular in the U.S. that it enabled the funeral home to replace the home as the place where people grieved, Fox said. As a result, death became increasingly commercialized as it was taken out of the domestic setting and put into a commercial one.

After the Civil War, a movement grew to rebury in marked graves those hastily laid to rest on the battlefield. Led in the South by private associations of women, in the North this push constituted the largest federal government initiative of its time. What started as a reburial movement for soldiers grew to provide care for their widows and orphans, then spread to the general population, thus sowing the seeds for the birth of the welfare state and the New Deal.

An American taboo?

Today, better health care, lower infant mortality and longer life expectancy mean that death has receded in familiarity for everyone except the very ill and very old. Does that modern lack of experience with death translate into our unwillingness to talk about it or accept it?

“Death is more removed from our daily experience than it was in the past,” Deverell noted. “While it once had its chin on the shoulder of people as they walked through life, death is now, for the lucky majority, a step behind us. It’s only when we think about those among us who are elderly or ill, that we then start to see death take a step forward.”

O’Neill argues that behind falling mortality rates and increased secularization lies a growing faith in science and our ability to control and even cheat death.

“Previously death was inevitable. It was more about how you died, whereas now we’re much more interested in prolonging life,” O’Neill said. “When death happens now, it’s a recognition of the limits of our abilities to control life. Death becomes perceived as a failure, feeding into the taboo that we don’t really want to talk about it or recognize it.”

The fact that we often characterize Victorian attitudes to death as morbid and obsessive offers telling insights into our own often uncomfortable relationship with mortality. It’s a relationship that Jody Vallejo, for one, doesn’t consider any healthier.

“People always have death on their mind, whether they admit it or not.”“There’s an obsession in America with not acknowledging mortality or aging,” observed Vallejo. The associate professor of sociology and American studies and ethnicity researches immigrant integration with a particular focus on the Mexican-origin middle class in the U.S. “Since the 1960s, there’s been a national obsession with looking youthful, reflected by the surging demand for plastic surgery and Botox,” she added.

In the meantime, death in America has mostly been removed from public view, taken out of the familiar and intimate confines of the home and transferred into the antiseptic, sterile environment of the hospital, where it is managed by medical professionals.

At one end of the spectrum, the elderly are hidden away in retirement homes, and at the other, children are sheltered from death by well-meaning parents who believe their offspring need protecting from the reality of mortality. That doesn’t happen in Mexico, Vallejo says, where beliefs and practices about death are integrated into everyday life.

“Kids attend funerals from the time that they are young children. The novena — a prayer ritual practiced by Mexican Catholics— is held for nine consecutive days, often in a family member’s home, where relatives and friends mourn and pray. It’s just part of life,” she explained. “The U.S. is generally a death-denying society and we are failing to see that the dying and the dead have a legacy to offer — connection to our past, to our roots, not just our family, but our community, our society.”

If death is a taboo subject in the U.S., Vallejo says, that doesn’t mean Americans aren’t fascinated with it. All you have to do, she says, is look at entertainment.

“We live in a society that’s obsessed with violent death in movies, TV shows and video games, but that doesn’t really acknowledge death and mortality except in these fantastical ways,” she said, referring to the current wave of vampire and zombie dramas.

“We are constantly confronted with death in American society. However, it’s present in ways that aren’t discussed or that allow people to actually think about their own mortality in a spiritual or contemplative way that could help them make sense of their own lives and the world around them.”

Vallejo believes that the growing popularity in broader American society of Mexico’s Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) — a celebration to remember and honor the dead — is partly rooted in how it allows people to think about death in ways made difficult by their own culture.

In Los Angeles alone, some 40,000 people attend the annual Dia de los Muertos celebrations at Hollywood Forever cemetery.

“You see Dia de los Muertos celebrations and symbolism everywhere in the U.S. now,” said Vallejo, commenting on the prevalence of Dia de Los Muertos folk art, costumes, tattoos and skateboarder imagery. “It’s yet another example of how death inevitably becomes commercialized in American society. Even Walmart sells sugar skulls. But it’s also emblematic of the ways in which immigrants help to remake societies.”

Death rituals differ across time and cultures, between classes and races, but all are endlessly interesting in terms of narrative, drama, poignancy, love, faith, grief, goodbyes and loss, Deverell noted.

“People always have death on their mind, whether they admit it or not,” he said. “I find comfort as a historian in the river of humanity and mortality that we’re all in. No one gets out of it, and there are lessons to be learned and inspirations to be gathered from those that came before us for all kinds of reasons.”

Read more stories from USC Dornsife Magazine’s Fall 2017-Winter 2018 issue >>