California Poet Laureate Dana Gioia brings poetry to the people in a two-year tour

California has long beckoned the writer’s imagination. From the Redwood Curtain to the Mojave Desert, California’s long coastal flank and rich landscapes of vast valleys and forests and distinct mountains have inspired the work of many writers and poets.

In 2016, California Poet Laureate Dana Gioia announced a challenge that would further familiarize him with his home state and expand poetry’s cultural reach: He would visit all of California’s 58 counties over the course of two years and lead poetry events at each.

Since then, Gioia, Judge Widney Professor of Poetry and Public Culture at USC Dornsife and USC Price School of Public Policy, has driven thousands of miles, often accompanied by his wife, Mary Hiecke Gioia, and an audio book or two. Each tick of the odometer has marked a steady burn through three sets of tires as the poetry missionary zigzags up and down the narrow roads that cling to mountains and stirs the dust in desert towns where visitors are novelty. Throughout this modern-day odyssey, Gioia has brought poetry to the people, and he has heard poetry of and by the people.

This is how Gioia saves poetry.

“There is always this debate in public arts policy about who you serve. Do you serve the artist? Serve youth? Serve minorities?” says Gioia. “There is only one proper answer in a democracy. We must serve everyone.”

‘Poetry is for everyone’

For years, Gioia has written commentary and criticisms about modern poetry, and in particular, about its exclusivity. In his 1991 landmark essay “Can Poetry Matter?,” published in The Atlantic, Gioia lamented that ownership and appreciation for poetry had shifted from “bohemia to bureaucracy,” confined by academic writing programs that emphasized analysis and criticism rather than performance and writing.

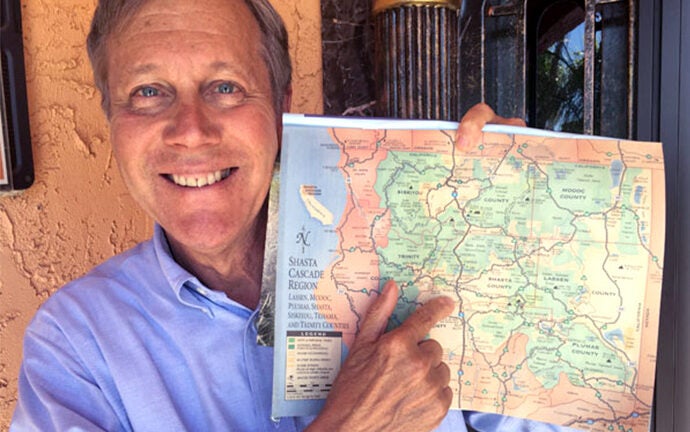

Dana Gioia in front of Burney Falls in Modoc County, Calif.

“I would wish that poetry could again become a part of American public culture,” he wrote. “I don’t think this is impossible. All it would require is that poets and poetry teachers take responsibility for bringing their art to the public.”

He then issued a call to action, advising that poets read aloud others’ works at their readings; asking arts administrators, when planning readings, to put on an inspiring cultural display of literature with music and other arts; encouraging poets to write prose about poetry more often; and insisting that poets who curate anthologies select only the poems they admire.

“Poets and arts administrators should use radio to expand the art’s audience,” he wrote. And poetry teachers “should spend less time on analysis on more on performance.”

Gioia has practiced what he preached. Since that essay, he has emerged as a vociferous advocate for arts and culture, building political support for arts and cultural programs nationwide. The New York Times credited him in 2008 as the poet who “resuscitated congressional support for the National Endowment for the Arts” during his chairmanship for the organization from 2002 to 2008.

Seven years and several writings later, Gioia heard from a stranger who intended to nominate him for California poet laureate. Gioia told her: “Don’t nominate me. I’m unlikely to be chosen.” A few months later, Gov. Jerry Brown appointed Gioia, making him the 10th California poet laureate since the position was established in 1915.

As part of the post, the laureate is encouraged to traverse the state and take on a cultural project.

“The decision to visit every county completely embodies the spirit of the poet laureate position, but it is not a requirement, and it has never been done before,” said Anne Bown-Crawford, executive director of the California Arts Council. “It’s a very ambitious undertaking. He has found an audience for poetry everywhere he has been, and he’s thoughtful and deliberate in his intention to include local artists and students in his events.”

In the state’s announcement of his appointment, Gioia declared, “Poetry is for everyone.”

When he says “everyone,” he thinks of his own working-class family.

Unconventional path to poetry

His Sicilian father drove a taxi cab and his Mexican mother worked for the phone company. Gioia and his family lived with his grandparents and other relatives in a cluster of apartments in Hawthorne in South Los Angeles. Poverty was in pursuit. Poetry was precious.

“My mother loved poetry,” recalls Gioia, who was the first in his family to go to college. “She learned poems by heart in her childhood. When I went to Harvard and I was taught that poetry was going to be an intellectual vanguard, it didn’t make any sense to me. I had always understood poetry to be one of the normal human pleasures. I have led my unorthodox career as a poet guided by that knowledge.”

Dana Gioia at Presidio Cemetery in San Francisco County.

Gioia’s unconventional path to poetry included a stint as a vice president for General Foods, overseeing Jell-O and other brands after he had earned a master’s in business administration from Stanford University (1977), a master’s degree in comparative literature from Harvard University (1975) and a bachelor of arts from Stanford (1973). He immersed himself in writing shortly after the passing of his first-born son, whom Gioia remembers in poems such as “Planting a Sequoia.”

Gioia’s own work is cast as populist, andhe is often compared to Walt Whitman and Robert Frost. His poetic accomplishments extend beyond the bookshelf, as well. He has written three libretti and collaborated with jazz pianist and composer Helen Sung on a new album, Sung With Words.

“I don’t see the point of writing in a way which excludes the average listener,” Gioia says.

Hence, his Tour de Prose as state laureate.

Traveling laureate

On a recent visit to a library in Heber, Gioia drew a crowd of about 20 people — high turnout for Imperial County on the U.S.-Mexican border, where most people work long hours on the local farms that grow cantaloupe and green onions. Attendees wrote and read poetry and made poetry books from recycled materials, says Crystal Duran, the county librarian who coordinated the event with Gioia.

“Everybody loved meeting Dana,” Duran says.

Gioia has just three counties left on his tour: Kings, Merced and Santa Barbara. He plans to visit them all this month.

Across the counties, he has collaborated with artists, musicians and students for the events. An array of poetry writers, readers and fans have attended, including teens serving time in juvenile detention centers, and school children who were most impressed that his birthday is on Christmas Eve and that his cat is named Doctor Gatsby. But the most important question that he heard on his tour so far came from an attendee at a July 2017 event in Madera County.

“This guy in the back asked, ‘Can someone without much education write poetry?’ I would never be asked that at Berkeley or Stanford. But it is a key question in our culture,” Gioia says. “So, we had an interesting 10-minute conversation about the fact that poetry began in the western tradition from people working the land. It started with the shepherds, including King David.”

On Oct. 6, Gioia will begin to draw the curtain on his tenure as California poet laureate by leading a statewide gathering of laureates from across the state at the McGroarty Arts Center in Los Angeles. The event features current and past laureates, including Los Angeles Poet Laureate Robin Coste Lewis, who is also USC Dornsife writer-in-residence, as well as former California poets laureate Carol Muske-Dukes, professor of English at USC Dornsife, and Al Young.

Gioia has traveled many roads rarely taken in the lead-up to this grand finale.

“His devotion of time and talent brought to every corner of the state has been extraordinary,” says Bown-Crawford. “The state is indebted to him for his generosity and dedication.”