Fighting for Inclusion

Nayan Shah was in South Africa on a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship during the most intense period of struggle against apartheid. Black resistors were being beaten, tortured and murdered.

It was 1989, a year before South African President Frederik Willem de Klerk began taking steps to end the country’s racial segregation policy.

Shah, who recently had completed his bachelor’s degree at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, decided to take a train to Durban. The then-21-year-old, whose parents had immigrated to the United States from India, wanted to trace the historic train ride a young Mohandas Gandhi took in 1893.

“When Gandhi took a train from Johannesburg to Durban he had this experience,” said Shah, who joined USC Dornsife as professor and chair of American studies and ethnicity this Fall. Dressed impeccably, Gandhi had bought a first-class ticket, but was ordered to a lower-class compartment. After refusing to move, Gandhi was thrown off the train.

“I was playing out a parallelism and seeing what had changed,” Shah said.

Buying a first-class ticket, Shah saw that the only other person in the first-class compartment was an Indian man, who was unpacking his dinner and offered Shah some food. Shah politely told the man he was going to eat in the dining car.

“Go right ahead,” the man wearily told Shah. Shah walked over to the dining car and saw that it was full.

A maître de told Shah that the next seating was in an hour. As he left, Shah noticed that all the diners were white.

“It didn’t work out?” the man in his compartment asked when he returned.

“I’m in for the next seating,” Shah told the man.

“Are you sure you won’t try some of my dinner I have here?” the man replied.

When Shah went back to the dining car for the next seating, he was the only diner in the room.

“At that moment, I realized, ‘Oh, that’s how apartheid works.’ They don’t want to make anyone too uncomfortable, so they have this system.”

Shah realized that the first-class compartments were segregated by race. Even the restroom he used was for nonwhite, first-class ticketholders.

But this was a watershed moment in history.

During his trip in South Africa, Shah worked with a grass-roots organization in Durban responding to housing, health and education needs of people who lived in informal settlements. Then, he learned about tens of thousands of anti-apartheid prisoners who were being held for years without trials. About 800 of these prisoners had gone on a mass hunger strike and were being released to hospitals. Some were sent to hospitals and later with the assistance of sympathetic medical workers escaped to European embassies and consulates.

The crisis of dying prisoners and national and international attention forced the apartheid government to release the prisoners. Before he left South Africa, Shah managed to meet one of the released detainees.

“He was not angry for being incarcerated for three years,” Shah recalled. “He could not see his family; he could not see anyone. He had a broken body. They tortured him and he starved himself in order to get out. He believed that he had seen the worst that the apartheid regime could mete out and they flinched. He predicted that apartheid would end. This was eight months before Mandela was released.”

Shah wondered how people isolated in detention centers knew that a hunger strike was taking place and built on it.

“These were not charismatic and seasoned leaders like Gandhi or Cesar Chavez. These were kids. Fourteen- to 24-year-olds. Going on a hunger strike for more than 21 days required incredibly conviction, self-discipline and support.”

Twenty-three years and two books later, Shah is revisiting South Africa in a new research project. He’s using the example of South Africa and the end of apartheid to help explain how and why hunger strikes have grown as a protest strategy for those incarcerated. He returned to South Africa twice to examine extraordinary records kept by detainees support groups, human rights lawyers, and progressive medical and social work organizations.

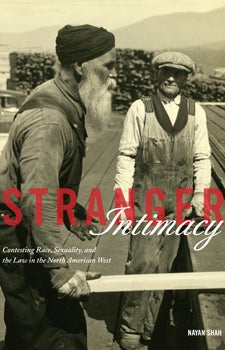

Shah’s award-winning book, Stranger Intimacy: Contesting Race, Sexuality and the Law in the North American West (University of California Press, 2011), uses compelling real-life stories to describe the lives of South Asian migrants in the western U.S. and Canada in the early 20th century.

“I’m looking at South Africa as a snapshot to help understand why people choose slow death as a method of protest,” he said. “And how it changes our ideas around medical ethics. Physicians are dealing with someone who is saying, ‘Don’t revive me; I do not want to be revived for further torture. In my conscious decision I’ve decided I’m willing to die.’ So the doctor asks, ‘What do I do? Do I follow my oath and revive this person so they can be returned for torture?’ Legally the doctor has to, but ethically what do they do?”

Shah’s research addresses how the South African hunger strikes raised this quandary in debates over medical ethics by the World Medical Association and the World Health Organization in the early 1990s.

His current project follows his latest book, Stranger Intimacy: Contesting Race, Sexuality and the Law in the North American West (University of California Press, 2011). Examining court, library and historic society records in the U.S., Britain and Canada, Shah uses compelling real life stories to describe the lives of South Asian migrants in the western U.S. and Canada in the early 20th century.

The book was the winner of the 2012 Norris and Carol Hundley Prize from the Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association (AHA). The award is given annually for the most distinguished book on any historical subject submitted by a scholar living within the 22 western states or four Canadian provinces from which the branch draws its membership.

“Shah’s innovative and deeply researched study illuminates the lives of individuals and communities struggling for whatever precarious foothold of love, hope and connection they can find within a hostile world,” said Peter Blodgett, executive director of AHA-Pacific Coast Branch. “His book challenges the orthodoxies of ‘settler’ societies in the American West by excavating long-forgotten news accounts, court records and immigration documents to reveal lives far more complicated than the proscriptive patterns of popular myth.”

Shah has been exposed to migrant issues since he was a child growing up in Montgomery County, Md. In contrast to most of the suburban communities in the county, his neighborhood was filled with Greek, Italian, Jewish, African American and Central American families. Years later, he realized that his family had moved into a neighborhood adhering to the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex and national origin.

Still, he remembers a time when a couple of new white children called him and his brother racial epithets, which escalated into his house being egged.

Many of the neighbors intervened and the mistreatment stopped. Nearly 45 years later, Shah’s parents still live in the home and are dear friends with their neighbors.

“Our neighbors rallied around and said, “This is not who we are,’ ” Shah recalled. “How amazing it was that they gave my parents and brother and me this world where we didn’t feel the searing experience of racial hatred.”

At Swarthmore College, Shah spearheaded a project meant to address incidents of racial hostility on campus after incidents of racial profiling and graffiti aimed at black students. Along with fellow students, he held discussion workshops in the dormitories that used videos depicting ways to resolve conflicts and better communicate. They invited civil rights leaders to campus to discuss the challenges of creating communities of racial harmony and understanding with students, staff and faculty.

After his Watson Fellowship took him to England, Kenya, and India as well as South Africa, he earned his master’s and Ph.D. at the University of Chicago. Before joining USC Dornsife, Shah was a professor of history at the University of California, San Diego.

He said he’s excited about this new post.

“Nationally and internationally, USC Dornsife’s ASE has zoomed from being a Ph.D. program that didn’t exist a decade ago to one of the top three Ph.D. programs in terms of placement,” Shah said. “We need to make sure it stays there and becomes a preeminent site of research, teaching and community engagement in Los Angeles. We believe ASE will be the West Coast incubating center for American and ethnic studies.”