A tall steel wall marks the border between the U.S. and Mexico

An IACS Dispatch from the Southern U.S. Border

Editor’s note: IACS DePaul Fellow Leo Guardado, Ph.D., recently led a group of Fordham University faculty to the U.S.-Mexico border for a week-long learning experience focused on migration. In the dispatch below, he describes how migrants are forced to wait at the border and the adverse effects of the new CBP One phone app that all asylum seekers must use.

NOGALES, Mexico — “How has the journey been for the kids?”

That’s a question my colleague asked the mom of three children with whom we had started to speak after we finished serving lunch at the Kino Border Initiative in this city near the U.S.-Mexico border.

“My daughter takes it like it’s a walk…she doesn’t know what’s going on…they’re innocent,” responded the mother in Spanish, pointing to her three-year-old daughter, the youngest of her children. Along with another mother who was journeying with her baby in her arms, these two women and their kids had left their respective towns in the southern tip of Mexico to seek asylum in the U.S. One came from Chiapas and the other from Campeche.

Our group witnessed more than a hundred people come through the dining hall of Kino, encountering not only a warm meal but also a sense of community in addition to legal, medical and psychological support. We asked migrants what it was like to be around so many others who were living through similar circumstances.

“Some are happy because they are going to cross, but the two of us don’t even have an appointment yet…we knew nothing about the asylum process so we just presented ourselves to border patrol [at the port of entry],” one of the mothers added. “I don’t want to risk crossing [the desert] with my children. I only knew about this place [Kino], but nothing else about crossing or asylum.”

Since these two women were running from gender-based violence and threats of kidnapping tied to local governments, we asked if they had already applied for asylum, only to find out that getting an appointment can take up to six months.

***

Nogales. San Ysidro. Eagle Pass.

Each port of entry was listed as an asylum interview location on the cracked cell phone screen that one of the mothers was holding as she looked at me with exasperation in her eyes, adding “one has to do this all day every day.” Her friend quickly added that clicking away on the screen takes up the whole day, wasting the phone battery, only to then wait to charge the phone. In shelters for migrants where dozens or even hundreds of other asylum seekers are also trying to charge phones to click away the day on the CBP One app, finding a free outlet can be challenging. Some, we were told, get up in the middle of the night to try their luck.

According to officials from the Biden administration, the CBP One app online appointment portal is meant to “significantly reduce wait times and crowds at U.S. ports of entry and allow for safe, orderly and humane processing.” The app is focused on maintaining “order” at ports of entry by more effectively controlling who can approach to ask for asylum. By keeping the physical bodies of asylum seekers away and delegating the reception of their presence to a digital app, the U.S. is trying to argue that it is still technically fulfilling its legal responsibilities to those who seek asylum. In fact, when we crossed on foot into Mexico through the port of entry at Nogales we saw two CBP agents stationed exactly at the point where Mexico and the U.S. meet. Their job was to turn away any asylum seeker who approached without a CBP One app appointment.

In “Ikiru,” the classic 1952 film by Akira Kurosawa, a group of women spend their days approaching local government bureaucrats asking them to actually do their jobs as public servants. The women want to improve the living conditions of their children by having a local cesspool cleaned up and a playground built over it. Each department disavows their responsibility and passes them on to another office — “go to the parks department,” “it’s a matter of sanitation,” “it’s for disease control,” “it’s a problem for the sewage department,” “go to zoning,” “to the city councilman,” “to the deputy mayor,” “go to public affairs,” “visit public works.”

Finally, the patience of one of the mothers in the film breaks and she exclaims: “How dare you, stop giving us the turnaround… we’re not idlers like all of you…all you do is laugh at us…you call this democracy?”

***

Laredo. El Paso. Brownsville. Hidalgo.

Four more choices to pick from for an asylum appointment. But when you click, the screen displays: No hay franjas horarias disponibles [there are no time slots available]. You try again, and again, and again, until the battery dies. The ritual will continue when an outlet becomes available and you are able to purchase more data for your phone.

“The app is a digital border wall — one more attempt to keep the physical presence of asylum seekers away from ports of entry.”

For asylum seekers, the CBP One app is now their first direct interaction with the United States of America, which sets forth the social grammars that will condition future interactions between “the state” and its poor clients. In his book, Patients of the State, Javier Auyero argues that “seemingly arbitrary, ambiguous, and always changing state requirements” (p.9) are meant to create subordinates of the state, and thus, waiting is not simply wasted or “dead” time created by an inefficient system, but rather, it is productive time for the state to make subjects into patients —people who know in their flesh the condition of long suffering and who recognize that the state is the source and possibility of their (legal) existence.

With the mothers from Kurosawa’s film Ikiru, we can ask: “You call this democracy?”

The mothers at Kino will use the time of waiting to find jobs, likely in maquiladoras at the border. They will take turns caring for each other’s children while they work. In small ways within enormous constraints, migrants exercise their agency, at times simply by showing up without appointments, or by attempting to cross the borders and ports of entry of the U.S. Each attempt resists the mundane bureaucracy that threatens genuine democracy.

The CBP One app is a digital bureaucratic replacement of the much-maligned Title 42 policy that justified the expulsion of asylum seekers, and which is set to end on May 11, 2023. The app is a digital border wall — one more attempt to keep the physical presence of asylum seekers away from ports of entry. Bureaucracy, as is known from 20th century history, can serve as an effective and efficient tool of death, controlling who lives, who is killed and who is left to die. Francisco Cantú, an ex-border patrol agent and author of The Line Becomes a River, reminds readers that “violence does not grow organically in our deserts or at our borders. It has arrived there through policy” (p.258). The violence of forced expulsion and the months of waiting in the borderlands can be understood as a U.S. policy designed to break the spirits and bodies of migrants, leaving them as targets of organized crime.

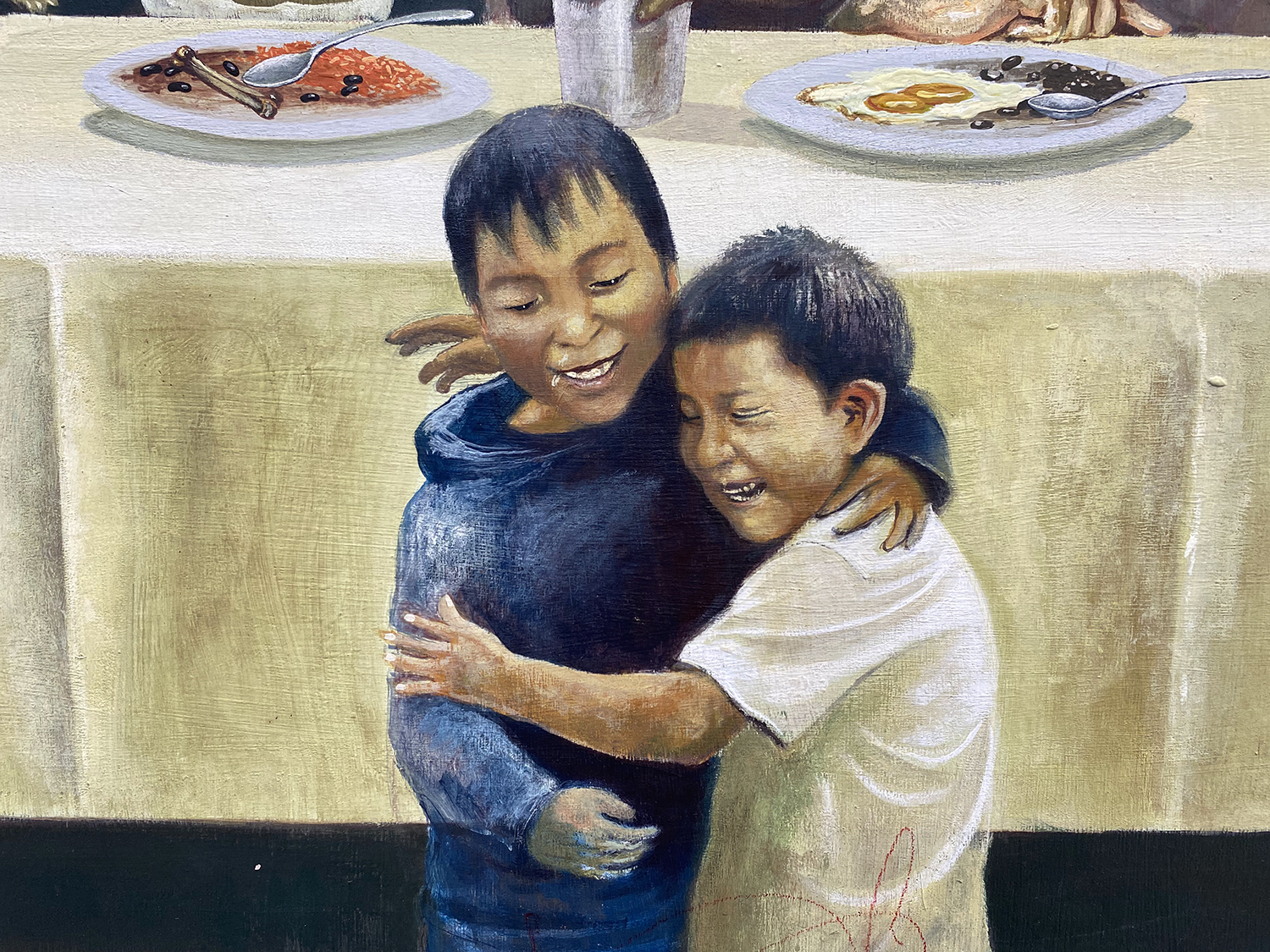

As I spoke with the two mothers from the southern tip of Mexico, their kids were running in the dining area of Kino, laughing and chasing each other to expel the deadly boredom they are made to endure. A mural at Casa Misericordia, a migrant-run shelter in Nogales coordinated by Sr. Angelica (“Lika”) with the support of various Christian denominations in Arizona captures the holiness of joy expressed by the children: “El mejor lugar para vivir es donde no tienes miedo de nadie y de nada, donde puedes correr sin miedo y no correr por miedo” [The best place to live is where you do not fear anyone or anything, where you can run without fear and not run because of fear].

For now, the children must run in the shelters, making joy from boredom, while their mothers smile, momentarily distracted from the cracked screen on the phone that will need to be clicked, again and again in the months to come.

No app is needed to have a life-giving encounter with the humanitarian organizations at the border and with the migrant communities who temporarily dwell there. Most of these organizations and shelters are faith-based, and they rekindle hope in a religion that too often resembles the dehumanizing bureaucracy of the state. The source of the hope is migrants themselves, whose agency as subjects of their own history is manifest in their struggle for life and freedom, despite the persecution they face on both sides of the border. Migrant communities and the organizations with whom they work point to the grassroot foundations of a genuine democracy that may still be possible if we are willing to imagine and construct ways of being with each other that do not depend on countless clicks.