How Faith Identity Shapes Support for Deportation in the U.S.

By James Ron and Richard Wood

Few issues cut as deeply into the fabric of American democracy as debates over immigration and deportation. From presidential campaigns centered on building walls to grassroots movements creating sanctuary cities, debates over deportation, citizenship, and belonging reveal not just policy disputes but also moral visions of the nation itself.

Religion has long played an ambiguous role in these polemics. Faith traditions have provided both the language of inclusion, through sermons on hospitality, solidarity, and the sanctity of the stranger, as well as the logic of exclusion, cloaking restrictionist impulses in religiously inflected notions of identity and tradition.

Most religious traditions themselves have complex official teachings on this terrain. Some may veer into exclusionary rhetoric, others will endorse the legitimacy of reasonable governmental immigration controls, and still others call for the humanitarian treatment of all immigrants and refugees.

To better understand how religion shapes attitudes toward deportation, this essay’s first author, James Ron, fielded a nationally representative survey in 2018 through YouGov, sampling 2,000 U.S. adults and weighting responses to match census parameters. The survey asked about religious affiliation, the personal importance of religion – which we term “religious salience” – and views on immigration and deportation.

To be sure, these data are now seven years old, and some of the findings may have changed. If we were to run the same poll today, for example, the precise percentage of respondents supporting deportation would likely be different. Still, the relationships between variables have likely endured, and for our purposes, this is what matters.

Our analysis uncovered two key findings. First, Americans who identify as “born again” are more likely to support deportation, especially when they believe religion is an important force in their lives. This is not true, however, for Catholics and Protestants who do not identify as born again.

Second, we discovered a striking paradox. Americans who claim no religious affiliation, but who also do not identify as atheists or agnostics, tend to support deportation the more religion is salient in their lives. This group of religiously unaffiliated (but not secular) Americans comprises 19% of our nationally representative sample.

This finding challenges assumptions that religiously unaffiliated Americans lean toward inclusivity. Instead, it suggests that religious energy, when detached from institutional guardrails, may fuse with nativist sentiment to legitimize exclusionary policies, particularly under agitation by anti-immigrant influencers in the wider political culture.

Religion, National Identity, and Deportation

Religion has always been entangled with U.S. immigration politics. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Protestant anxieties fueled exclusionary laws targeting Catholics, Jews, and Asians. More recently, religious conservatives have mobilized to restrict Muslim immigration, while progressive faith coalitions have defended undocumented migrants.

Most research on religion and politics emphasizes institutional affiliation, that is, whether someone identifies as Protestant, Catholic, Evangelical, Jewish, Muslim, or other. Affiliation, however, only tells part of the story.

As noted above, almost one-fifth of our sample described themselves as belonging to “no religious tradition in particular.” Of those, roughly halfhigh levels of religious salience in their daily lives. This group complicates easy binaries of “secular versus religious,” and reveals new currents of moral and political behavior.

Bivariate Findings

First, we explore relationships between two variables, called in statistical parlance “bivariate relationships.” These relatively simple findings can be revealing and are commonly used among pollsters reporting results to their clients or to the media.

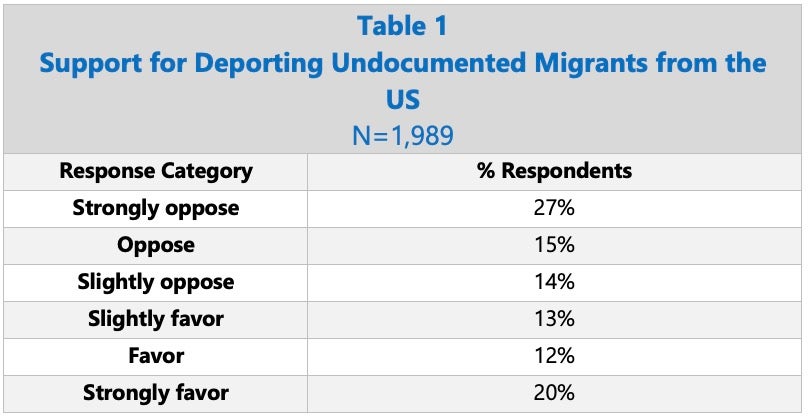

We begin by describing responses to a simple question we posed about attitudes towards deportation. Table 1 presents responses to the query, “Do you favor or oppose deporting immigrants who are in the United States illegally?” The table shows that 56% of our sample opposed deportation to varying degrees, while 46% were in favor (the total number of respondents was 1,989, as 11 did not answer the question). Roughly 47% of these were strongly wedded to their views; 27% were “strongly opposed,” and 20% were “strongly in favor,” with another 53% holding less intense “oppose” or “favor” positions. Once again, these numbers have likely changed somewhat in the intervening years.

Table 2 reports that the largest group in our sample (29%) self-identified as born-again, while the second-largest group reported that, religiously, they affiliated with “nothing in particular” (19%). These were followed by Roman Catholics (16%), non-born-again Protestants (14%), Atheists (7%), and Agnostics (6%). As is true for the American population overall, respondents from other faith traditions were far fewer in our sample: people who identified as Jews (2%), Mormons and Buddhists (1%), and Orthodox, Muslims, and Hindus (less than 1%).

The number of “nothing in particular” respondents is striking, as almost one in five persons in our sample were faith-oriented but institutionally unaffiliated.

Next, consider responses to our question about religious salience. In our sample, 39% said religion was “very important to them,” 27% reported it was “somewhat important,” 13% believed it was “not very important,” and 22% said it was “not at all important.” If we combine the top two categories and extrapolate to the general population – a maneuver that seems justified, given the representative nature of YouGov’s best-in-class sampling procedures – fully 66% of Americans in 2018 believed that religion was a significant force in their lives. That number is likely similar today.

As many scholars have pointed out, US society is very faith-oriented.

To learn how religious salience varied by faith tradition, Table 3 visualizes the bivariate relationship. On a scale of 1-4, in which 4 signifies the highest level of religious importance, born-again Americans ranked highest on religious salience, with an average of 3.7, followed by Muslims (3.33) and Mormons (3.24). Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholics were tied at 3.11, followed by non-born-again Protestants (3.06). Hindus, Jewish people, and Buddhists all scored in the 2-range, as did those who identified as “nothing in particular.” For agnostics and atheists, not surprisingly, the importance of religion was just a hair above 1, or “not at all.”

Next, we explored the bivariate relationship between religious salience and deportation, finding that the two were positively correlated. People who scored high on religious salience also scored higher on the support for deportation scale (3.7, on average, on the 1-6 scale, in which 6 signified the strongest pro-deportation sentiment). Respondents with low religious salience supported deportation at the 2.5 level, on average. At first blush, at least, religious salience seems positively associated with support for deportation.

Table 4 explores the two-way (“bivariate”) relationship between religious denomination and support for deportation.

Eastern Orthodox favored deportation the most, but given their tiny numbers in our sample, this finding should be taken with a very large grain of salt. The same is true of the other smaller denominations, including Muslims, Hindus, Jews, and Buddhists. To truly estimate their support for deportation, we would have had to generously “oversample” those populations, which this poll did not do.

Among the larger denominations, born-agains were the most pro-deportation (3.81 on the 1-6 scale), followed by Roman Catholics (3.59), “nothing in particular” (3.25), and non-born-again Protestants (3.13).

These findings suggest a three-way relationship between religious salience, religious denomination, and support for deportation. Born-again Americans, for example, are the most likely group to say religion is important in their lives, and they are also the most pro-deportation of the major faith traditions.

The “nothing in particular” group, however, presents a puzzle. Their religious salience score was comparatively low, but their support for deportation was comparatively high. This suggests that religious salience and religious denomination do not, on their own, drive American attitudes towards deportation.

Setting up the Multivariate Analysis

Scholars often move beyond the simple two-way, bivariate findings presented by pollsters, knowing that social reality, including public opinion, is often maddeningly complex. The public’s attitudes towards a given topic are shaped by myriad factors, including “hard” variables such as age, gender, income, employment status, or education, and “soft” variables such as opinions on other issues, including politics, race, and more.

To build a more accurate understanding of the relationship between denomination, religious salience, and attitudes towards deportation, we built a complex statistical model. Our “dependent variable” – the thing we wanted to explain – was support for deportation, which we arithmetically transformed to represent “standard deviations from the mean” for each religious denomination. This is a more realistic way of comparing apples to apples. (Those less interested in the methodological details might skip to the findings section below.)

Our “independent variable of interest” – the factor whose impact we are interested in exploring – was an interaction between denomination and religious salience. To simplify matters, we collapsed our religious denominations into the four main groups – born-again, Catholics, Protestants, and “nothing in particular” – along with a fifth catch-all group, “other,” which included all of the smaller subgroupings lumped together.

Our control variables included a wide range of potential covariates, including:

- Sociodemographics (gender, age, education, estimated family income – with an additional assessment of income’s ability to meet expenses, employment status, marital status, region of the country, and nature of the respondent’s place of residence – city, suburb, town, or rural)

- Religious behavior (frequency of prayer and church attendance)

- Political behavior (political partisanship and voter registration)

- Racial and political attitudes (populism, nativism, and white nationalism)

We used an Ordinary Least Squares statistical model with a Variance Inflation Factor test for multicollinearity (to see whether the covariates were too tightly correlated). We then re-ran the model with an estimator for something called “robust standard errors,” a procedure that adjusts for potential irregularities in the data. It makes our uncertainty estimates more reliable and renders our conclusions more cautious.

Overall, our statistical model was gratifyingly strong. The “R-squared” statistic – which tells us how much of the variation in support for deportation our model explains – was 68.5%, a very high number for public opinion analyses. Further confirmation comes from the model’s “F-statistic” of 115.5, which tells us that when taken together, the model’s explanatory factors – its independent variable and controls –collectively explain a statistically significant portion of the outcome.

Our model, in other words, explains a lot of the outcome (which statisticians call the “variation”), and the above-cited numbers show this is not due to mere chance.

Multivariate Findings

Importantly, the model’s most important predictors were not religious. Not surprisingly, the lead factors shaping American attitudes towards deportation in 2018 were white nationalism – the belief in the importance of America being populated and dominated by white people, and nativism, or the belief that immigration by culturally, ethnically, or religiously distinct groups poses a threat to the country’s social cohesion, economy, and values.

In addition, both Republicans and Independents were more likely than Democrats to favor deportation, as were older respondents. People without a four-year education were more likely to be pro-deportation than those with college degrees, and so were employed people, when compared to retired respondents. Town-dwellers were more pro-deportation when compared to city dwellers, but this was not true for residents of suburbs and rural areas.

Other factors in our model were not significantly associated with views on deportation, including income, marital status, gender, voter registration, frequency of prayer, church attendance, and the region of the country where the respondent lived.

What about Religious Denomination and Salience?

To our surprise, religious denomination and religious salience – on their own – did NOT have a statistically significant relationship with respondents’ support for deportation. This flies in the face of the bivariate findings noted above, which appeared to suggest a strong relationship. This finding by itself confirms the importance of using more complex “multivariate models,” and not stopping with the simple, two-way analyses commonly used by media-oriented pollsters.

What did matter, however, was the interaction between religious salience and denomination, and it is here that we come to our most interesting findings.

For two religious groups – the born-again and those who said they were affiliated with “nothing in particular” – the more respondents felt that religion was important to their lives, the more pro-deportation they were. Religious salience, combined with self-reported born-again or “nothing in particular” faith identities, had a positive, statistically significant, and substantively meaningful association with support for deportation.

To summarize: The strongest predictors of public support for deportation were white ethnonationalism, nativism, Republican/Independent partisanship, older age, lack of a college degree, town residence, and religious salience among the born-again and religiously unaffiliated. Other factors such as prayer, gender, income, and main religious identity played insignificant roles, once we controlled for everything else.

To put a finer point on it, support for deportation rises steadily and significantly with religious salience among born-again Christians, growing from 3.15 on the 1-6 scale at the lowest levels of salience to 3.74 at its highest levels, an increase of 19%. Among the “nothing in particulars” – people with no clear religious affiliation, but who nonetheless consider themselves religious – support for deportation increases from 3.23 at the lowest salience levels to 3.81 at the highest, an 18% increase.

Given how many other factors our models control for, and how complex public opinion prediction is, these are very large changes indeed.

A Note on Robust Standard Errors

It is important to note that while our primary regression model found statistically significant interaction effects, our confidence in these results was reduced somewhat when we applied the robust standard error procedure. As noted above, robust standard errors are a conservative statistical technique that adjusts for quirks in the data, including unequal variance in error terms, a phenomenon called “heteroskedasticity.”

Under this more cautious estimation, the born-again interaction term no longer meets the conventional 95% confidence threshold, though its direction and size remain consistent with the primary model. The same is true for the “nothing in particular” interaction, which also drops just below statistical significance. This suggests that the observed patterns are substantively meaningful but should be interpreted with caution. They should also be further studied and broadly discussed by a public concerned about the positive and negative ways that religious and identity discourses shape political views.

Conclusion: Religion, Identity, and the Politics of Belonging

Our findings add nuance to the public understanding of how religion shapes attitudes toward immigration and deportation in the US. While religious denomination alone does not predict support for deportation once other factors are controlled, religious salience—the personal importance of religion—does matter, but only for certain faith groups.

For born-again Christians, religiosity is correlated with increased support for deportation, even after adjusting for political affiliation, demographic background, and other factors, including racial ideology. Surprisingly, this same pattern holds for those identifying with “nothing in particular,” a large and growing segment of the U.S. population that is religiously unaffiliated, but not necessarily secular. When religion is important to members of this group, their attitudes toward undocumented immigrants grow markedly more exclusionary.

Together, these findings suggest that the moral energy of religion—when untethered from institutional structures—can operate in both inclusive and exclusionary ways, depending on the group. They also highlight the critical importance of attending to how religion is experienced and enacted, and not just simply whether someone is affiliated with this or that tradition.

As America continues to debate the meaning of national identity, these dynamics of religious salience and group identification will remain key to understanding the cultural battle over who belongs and who is cast out.

James Ron, PhD, is an author, sociologist, and political scientist. He shares his research insights on his LinkedIn, ResearchGate, and Google Scholar pages, as well as his professional and personal blogs.

Richard L. Wood, PhD, is president of the Institute for Advanced Catholic Studies (IACS) at the University of Southern California and professor emeritus of sociology at the University of New Mexico.

This post is the second post published by the IACS on the impact of religious salience on public opinion. For our previous post, see Opiate of the Masses? Evidence from Surveys in Mexico and Colombia.