Reflections on Resistance and Roots of Research from 2022-2023 Greenberg Research Fellow Raíssa Alonso

In this blog, the Center’s 2022-2023 Greenberg Research Fellow Raíssa Alonso reflects on resistance and the roots of her research.

Brazil has had a complicated political past. When you learn about the crimes of the military dictatorship (1964-1986), it’s striking how recently it ended. In my case, five years before I was born. My father was briefly part of a resistance movement when he was in his 20s, and we had relatives in both my mother and my father’s family who were persecuted, arrested, and tortured. When I was in college I actually got to read some of their files from the political police archives. And I always thought to myself: what would I have done if I were in their place?

The same questioning hit me when I started interviewing Holocaust survivors who came to Brazil, a project led by my advisor Maria Luiza Tucci Carneiro in the University of São Paulo.

The question burned in my mind for a long time. We always like to think of ourselves as heroes of our own story, but I was never sure if I could have summoned up the courage to resist an oppressive regime. I’m not a fighter who could take up arms and be part of a guerilla movement. I’m not an artist, gifted with the power to move people and sensibilize them. But the more I listened to Holocaust survivors’ stories, I felt that I could, at least, write about them. So when my advisor showed me evidence of documentation in the political police archives relating to an anti-Nazi resistance movement in Brazil, I jumped at the chance to write their story. I was naively hoping to rescue unsung heroes from the clutches of oblivion.

Instead, I found people. A small group of people, who had been forced to flee their country to resettle in Brazil, knowing nothing of its language or its people. People who had to do their best with whatever tools they had available at the time. People, in all their contradictions, struggling to survive and to do what they felt it was right. People whose efforts may have not saved the world, but who believed that there was worth in trying. They were teachers, directors, musicians, students, journalists. And even though they had an ocean between their new home and their motherland, they couldn’t stand to see what was happening in Europe and be quiet.

As I researched their lives, my own country became polarized between democracy and the possibility of being governed by someone who had publicly praised a well-known torturer from our dictatorial past, someone supported by the majority of the country in 2018. Could there be an “Other Brazil” movement as there was once an “Other Germany” one? Interestingly enough, in his first speech, President Lula addressed the crowd and stated: “There are no two Brazils.”

During these last four years, my research became something of a beacon of hope for me. These resistance groups I study had survived the horrors of the Nazi regime. They had fought to preserve their ideals and values in the worst of times. For the last four years, they have been my inspiration. As I wrote about them, I hoped that we too would overcome our own terror. I daresay we are in a better path now – or at least, in a moment of respite, perhaps, from the fascist wave that threatens to drown so many countries.

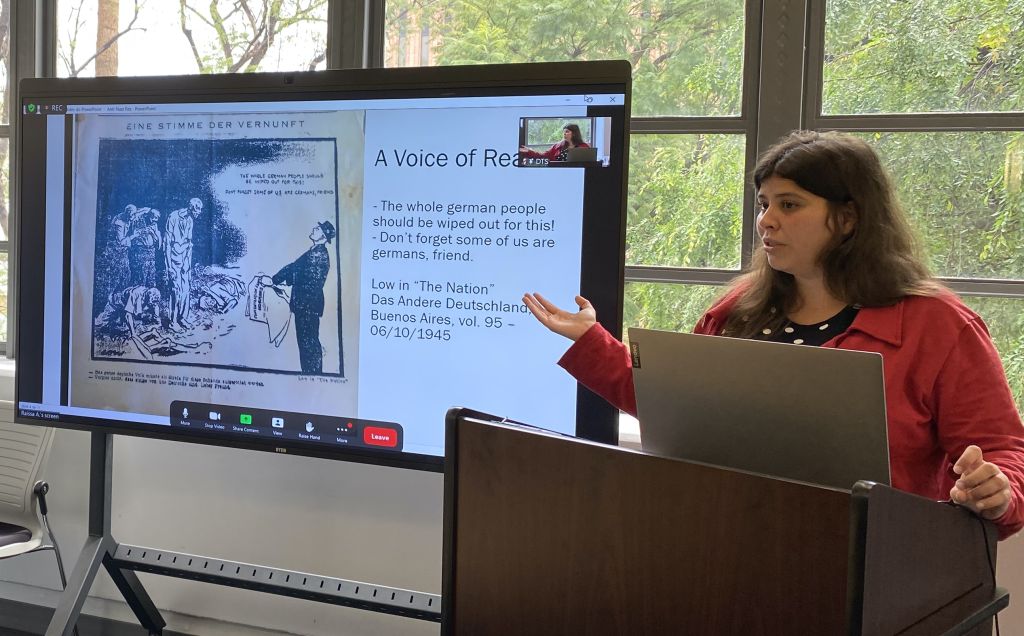

When people think of World War II and South America, they usually remember the massive numbers of Nazis that fled to South America after 1945. Even now, the German community of the time – comprised of immigrants, refugees, and their descendants – are still considered mostly Nazis in our history books: the Fifth Columnists.

I’m not trying to dispute the evidence that so many fine historians have presented us. There were certainly (a lot of) Nazis in Brazil and in Latin America as a whole. Many of them weren’t even German. And yet, I feel that we should also remember that where is fascism, there is always resistance. Their numbers may be small, but they exist. And in existing, they prove to us that we can always resist too, with our own tools and in our own ways. There is meaning in resisting. There is meaning in knowing we are not alone in this fight.

For my Ph.D., I wanted to see what connections could be made between the anti-Nazi resistance groups in the American continent. I knew the group I studied in Brazil had been in contact with others in Argentina and Mexico, but their leader had also been in contact with several artists and intellectuals residing in the United States. Listening to the testimonies of the Shoah Foundation and working with the archives from Heinrich Mann and Lion Feuchtwanger at USC renewed my inspiration. I saw in them my fears — what will happen to the future of my country? — and seeing their discussions unfold, I better understood my own present history.

Walter Benjamin once wrote that: “only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.” Benjamin didn’t live to see the end of the Nazi regime. Nonetheless, it ended. And it gives me comfort to know that if the enemy resurges, people will find a way to resist it too. And while the future is not set in stone, I feel hopeful that one day we can bury our dead in peace, because the enemy will have lost once again, this time for good.